by Tim Lacy

————————————————————————————————————–

[Note: This is the third USIH post in relation to “For the Love of Film: The Film Preservation Blogathon III.” Please see the introduction to Ben Alpers’ 2012 USIH blogathaon entry for more information. Click HERE to make a donation to the National Film Preservation Foundation.]

————————————————————————————————————–

My love and admiration for Hitchcock began with fuzzy UHF television reruns of the Alfred Hitchcock Presents (or “Hour,” if you prefer). As a kid, watching the Hitchcock Hour at my grandparents’ house, I admired the mystery and suspense of Hitchcock, as well as shows like The Twilight Zone. Each helped feed the impoverished imagination of a kid growing up in small-town, rural western Missouri. Later, during my adolescent and teenage years, I left Hitchcock behind for girls, science fiction, fantasy, and school concerns.

My love and admiration for Hitchcock began with fuzzy UHF television reruns of the Alfred Hitchcock Presents (or “Hour,” if you prefer). As a kid, watching the Hitchcock Hour at my grandparents’ house, I admired the mystery and suspense of Hitchcock, as well as shows like The Twilight Zone. Each helped feed the impoverished imagination of a kid growing up in small-town, rural western Missouri. Later, during my adolescent and teenage years, I left Hitchcock behind for girls, science fiction, fantasy, and school concerns.

Courtesy of cable television (i.e. AMC) and the need for breaks from reading and drinking during graduate school, I rediscovered Hitchcock. This time I experienced his work in film. So, in between readings of Foucault, Thomas Kuhn, Peter Novick, and other graduate school standards, I worked my way through the Hitchcock film bibliography. Despite my graduate thinking about canons (via the great books idea), I wasn’t concerned about screening only Hitchcock’s “greatest hits” from the Fifties and Sixties—Psycho, Vertigo, Rear Window, The Birds, North by Northwest, etc. I also watched his lesser known and less acclaimed films from the Seventies, Forties, and Thirties. I never made it to the early Thirties or his silent films from the Twenties. But I did screen Sabotage, Jamaica Inn, Rebecca, Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Suspicion, and Saboteur, among others. I recorded many of those AMC showings on VHS, and kept a log (yes, I’m a nerd like that) of my viewings in a copy of Donald Spoto’s The Dark Side of Genius (Little, Brown, 1983; Da Capo, 1999). Indeed, it was probably the 1999 Hitchcock centennial that prompted AMC to review so many of his films precisely when I was grad student (1998-2006—with breaks). In any case, it worked out for me.

Apart from mystery and suspense, this time around my interest in Hitchcock was maintained by an appreciation of his eye for set details, lighting, costumes, and varied locations, as well as his differing story lines, attention to camera angles, ear for music, and choices of actors—particularly his eye for the opposite sex. I also hadn’t lost my adolescent delight in Hitch’s sense of the macabre (e.g. his fascination with strangulation, corpses, etc.).[1] What’s interesting to me now is how I thought about and watched his films on his terms alone. I had apparently made a silent choice, this being a grad school hobby, to avoid thinking about Hitchcock contextually, in relation to the time of conception and production of his films. Given that, I never worked to understand how Hitchcock’s artistic choices and story ideas maintained relevance through screening. Production being what it is, both a linear and non-linear process, it is impossible to know what will be a “hit” with audiences upon release—to know what themes will remain relevant over the course of one, two, or three years. Then again, when you look closely at the production times between films, Hitchcock produced roughly one per year between 1925 and 1962. Amazing. When you’re that fast, you can replicate your audiences’ weltanshauungen.

Apart from mystery and suspense, this time around my interest in Hitchcock was maintained by an appreciation of his eye for set details, lighting, costumes, and varied locations, as well as his differing story lines, attention to camera angles, ear for music, and choices of actors—particularly his eye for the opposite sex. I also hadn’t lost my adolescent delight in Hitch’s sense of the macabre (e.g. his fascination with strangulation, corpses, etc.).[1] What’s interesting to me now is how I thought about and watched his films on his terms alone. I had apparently made a silent choice, this being a grad school hobby, to avoid thinking about Hitchcock contextually, in relation to the time of conception and production of his films. Given that, I never worked to understand how Hitchcock’s artistic choices and story ideas maintained relevance through screening. Production being what it is, both a linear and non-linear process, it is impossible to know what will be a “hit” with audiences upon release—to know what themes will remain relevant over the course of one, two, or three years. Then again, when you look closely at the production times between films, Hitchcock produced roughly one per year between 1925 and 1962. Amazing. When you’re that fast, you can replicate your audiences’ weltanshauungen.

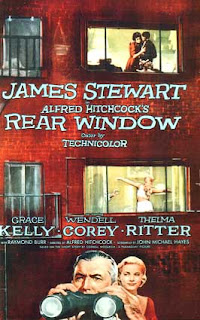

Today I want meditate on a Hitchcock classic—one of the top 50 all-time films (#48) according the American Film Institute: Rear Window. Produced in 1953 and released in 1954, Rear Window traced the homebound activities of a convalescent-but-formerly-world-traveling photo-journalist, L.B. Jefferies, smartly played by James Stewart, and his gorgeous, camera-friendly Manhattan socialite girlfriend, Lisa Carol Freemont (Grace kelly).  Confined to apparently sedate voyeuristic activities via his rear window, Jefferies comes to believe that a neighbor, Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr), has murdered his wife. At that point Jefferies convalescence becomes a detective activity, drawing in his caretaker, Stella (Thelma Ritter), and his old friend, the detective Tom Doyle (Wendell Corey). As Jefferies winds his way toward solving the mystery, trying to avoid attracting Thorwald’s attention to his snooping, Hitchcock introduces a memorable cast of side characters: the sad sack Miss Lonely Hearts (Judith Evelyn); the athletic, sexy ballet dancer, Miss Torso (Georgine Darcy); the friendly but disaffected “Composer” (Ross Bagdasarian); the unhappy newlyweds; and a spinster cat lady.[2] The film was based on a short story by Cornell Woolrich. The plot and more details are available at AMC’s Filmsite. It’s trivia, but it may be interesting to know that Grace kelly turned down the role of Eva Marie Saint in Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront to work with Hitchock instead.[3]

Confined to apparently sedate voyeuristic activities via his rear window, Jefferies comes to believe that a neighbor, Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr), has murdered his wife. At that point Jefferies convalescence becomes a detective activity, drawing in his caretaker, Stella (Thelma Ritter), and his old friend, the detective Tom Doyle (Wendell Corey). As Jefferies winds his way toward solving the mystery, trying to avoid attracting Thorwald’s attention to his snooping, Hitchcock introduces a memorable cast of side characters: the sad sack Miss Lonely Hearts (Judith Evelyn); the athletic, sexy ballet dancer, Miss Torso (Georgine Darcy); the friendly but disaffected “Composer” (Ross Bagdasarian); the unhappy newlyweds; and a spinster cat lady.[2] The film was based on a short story by Cornell Woolrich. The plot and more details are available at AMC’s Filmsite. It’s trivia, but it may be interesting to know that Grace kelly turned down the role of Eva Marie Saint in Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront to work with Hitchock instead.[3]

Rear Window premiered in August 4, 1954 at New York’s Rivoli Theater. Proceeds benefitted the American-Korean Foundation, which had been “formed to provide emotional and material relief” after the war. Apparently the film generated a “mob scene” at the Rivoli. Rear Window eventually garnered Hitchcock a best director nomination (one of five total in his career). Rear Window also grossed 10 million dollars by the end of 1956 (anywhere from $66.1-345 million in 2012 dollars). The film only cost about 2 million to produce. As an aside, just one year after taking up U.S. citizenship in 1955, Hitchcock earned 4 million dollars but, due to tax shelters, avoiding paying even “a cent of tax.”[4] This correlates with Alpers relaying that Hitchcock, while he tried to preserve his artistic integrity, thoroughly engaged the Hollywood scene. He was fine with manipulating capitalism to his own ends, when he could.

Spoto argued that Rear Window, along with To Catch a Thief, The Trouble with Harry, and The Man Who Knew Too Much, represents a “warm and comic” period—facilitated by screenwriter John Michael Hayes—in relation to Hitchcock’s general “emotional interest and aesthetic concern.” That period contrasted with “the obsessive fear of lost identity” in films like The Wrong Man, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, The Birds, and Marnie. Spoto characterizes the latter concern as a “resumption of his basic gravity” and a return to Hitchcock’s “profoundest concerns.” Still, in Rear Window, Hitchcock is merely a “chair-bound voyeur.” Stewart via Jefferies is Hitchcock’s “alter ego,” according to Spoto. And we, with Hitchcock, are “gazers” at the larger world—at murder, sex, loneliness—at modernity.[5]

And, during the Cold War in the Fifties, Americans were expected to merely gaze. They were to leave involvement and engagement to the politicians, the Brain Trust (i.e. the Eggheads), and the military. Americans were contained; they were “homeward bound” like Jefferies, though uninjured physically. The mere voyeurism was, oddly, vital to the national interest. Americans were to inform on the suspicious activities of others. Oddities were to be shunned, but were nevertheless the objects of our collective gaze. Since we could only police the common square (and not too vigorously debate in it), the terrified voyeurism of Americans was confined to their rear windows. As Lary May noted in the “Introduction” to his edited collection, Recasting America, Hitchcock “evoke[d] the [seeming?] harmony of the affluent world”—of the middle-class—and “then slowly reveal[ed] the irrational terror beneath the placid surface.”[6]

And, during the Cold War in the Fifties, Americans were expected to merely gaze. They were to leave involvement and engagement to the politicians, the Brain Trust (i.e. the Eggheads), and the military. Americans were contained; they were “homeward bound” like Jefferies, though uninjured physically. The mere voyeurism was, oddly, vital to the national interest. Americans were to inform on the suspicious activities of others. Oddities were to be shunned, but were nevertheless the objects of our collective gaze. Since we could only police the common square (and not too vigorously debate in it), the terrified voyeurism of Americans was confined to their rear windows. As Lary May noted in the “Introduction” to his edited collection, Recasting America, Hitchcock “evoke[d] the [seeming?] harmony of the affluent world”—of the middle-class—and “then slowly reveal[ed] the irrational terror beneath the placid surface.”[6]

One of the things I like about Rear Window is its use of framing. The various window frames outlining Miss Lonely Hearts, Miss Torso, The Composer, and the newlyweds speak to our limited understanding of the other. Those frames are a metaphor for our inability to understand the fuzzy edges, and beyond, of what’s outlined. Even when we’re looking out of harmless rear windows, we can’t understand the total context of what’s in our supposedly safe suburban backyards and tidy urban courtyards. We’re always missing some key part of the story. Jefferies spends all of his energy in the film trying to understand what he couldn’t see. He is symbolic of the heroic efforts we should all make to properly frame the truth. Of course he was driven by intuition, but he never stopped trying to verify his sense of the world, of right and wrong. Jefferies tried to understand, to rationalize, the world beyond his frame of reference.[7]

This is what Hitchcock saw in 1950s America—lonely Americans desperate to understand each other. Though this point was subsumed in a popular murder-suspense story, he nevertheless captured our containment on screen. Americans were alone together (with apologies to Sherry Turkle), watching each other through frames of fear—wondering what evils lurked out of view.

As an aside, despite my admiration for Jefferies’ tenacity in trying to discover the truth, one of things I disliked about Rear Window was how quickly Jefferies came to believe that Lars Thorwald killed his wife. And why did Hitchcock let it be the husband? Was it a kind of suburban containment fantasy—“spousicide”? Or was it because Thorwald looked like a killer?

Returning to my experiences watching Hitchcock while also a graduate student, and trying to connect my viewings with that graduate training, in retrospect I am surprised at how little his films were discussed in the cultural histories I read on the Forties, Fifties, and Sixties. In reviewing my notes from a few of those books, only Lary May’s The Big Tomrrow dealt with Hitchcock. May noted that Hitchcock dealt with “alienated, deranged characters,” and “hidden enemies,” but ultimately “assured viewers [in his films] that an orderly universe prevailed.”[8] Other than May, perhaps I simply did not read enough on film (e.g. in constructing my reading lists). But even the passing references to Hitchcock in other works are scarce. As demonstrated above, it is not difficult to read Rear Window as a product and reflection of the Cold War. Perhaps it’s too obvious. If my impression of Hitchcock citations in relation to the Cold War is off, I would greatly appreciate correction in the comments to this piece.

If you have not seen Rear Window, rent it or add it to your Netflix queue. After your screening, let me know if you too see it as a metaphor for the containment, suspicion, and voyeurism of the Cold War. I would be surprised if you don’t.

————————————————————-

Notes

[1] Donald Spoto, The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock (Boston: Da Capo Press, 1999), 331, 354.

[2] Spoto, 575; Gerald Mast and Bruce F. Kawin, A Short History of the Movies, sixth edition (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1996), 326-327.

[3] Spoto, 345.

[4] Spoto, 353, 360, 380, 499.

[5] Spoto, 346, 368-369, 408, 425.

[6] Lary May, “Introduction,” in Recasting America: Culture and POlitics in the Age of Cold War, ed. Lary May (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 7. See also Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 1999). I have not read John Fawell’s Hitchcock’s Rear Window: The Well-Made Film (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2001), but it apparently covers voyeurism as the central theme of the film. Fawell is a humanities professor at Boston University, and was trained in comparative literature at the University of Chicago.

[7] Mast and Kawin refer to “window frames as movie frames” in their discussion of Rear Window (p.328).

[8] Lary May, The Big Tomorrow: Hollywood and the Politics of the American Way (Chicagao: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 222.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Interesting post Tim- Your observation about the framed views of the characters is convincing and I would only add that it seems to me that Jefferie’s is viewing these characters from a even narrower lens, his telescopic camera, which makes his analysis more intrusive and myopic. Of course, knowing that Burr’s character did commit the murder removes the fuzzy edges and confirms that Americans need to be wary of commies/murders in their midst.

Was Hitchcock involved in the inquiries of the House on unamerican activities committee investigations?

@Paul: Good question! I don’t know. …Let me research for a minute. …I’m back: If I’ve read properly (and quickly) in Patrick McGilligan’s Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, it appears that Hitchcock himself was left alone by HUAC. – TL

I think you’re right that Hitchcock films are almost always relatable to their period, and you argue well for this one; I like the “frames of reference” notion.

Perhaps Hitchcock wasn’t included in cultural/social histories because he was so successful at framing (if I may use your term!) himself and his films as sui generis, as spectacles from the mind of one “master of suspense” rather than as pieces of popular culture.

And perhaps because we’re a chauvinistic nation(and because of genre)we didn’t see this Brit as making mainstream, truly American movies like a Capra or a Ford….

@Tinky: Thanks for the comment. As I noted in the piece above, Hitchcock had obtained citizenship right around the release of Rear Window. Of course citizenship never makes one a native, so there’s that. …I want to reiterate that I don’t know whether he’s been excluded from well done social and cultural histories on the period. It’s just that I can’t recall any where his work is cited as symbolic or as a metaphor for any particular year or period. …I just remembered, in typing this comment, that I meant to look into Stephen Whitfield’s Culture of the Cold War. …Just did that: Whitfield apparently doesn’t cite Hitchcock or Rear Window.

Terrific post linking 50s culture with Hitchcock’s voyeurism in this film. I would disagree with Lary May that an “orderly universe” ultimately prevailed in his films. Just the final shot from Rear Window, showing Grace Kelly picking up Vogue magazine and trying to hide it from Jeff, indicates a sense of discomfort and dissatisfaction; it always struck me as Hitch’s way of saying that this relationship would not be a happy one. Once we get into the late 50s-early 60s films, endings (eg, Psycho, Vertigo) usually lack closure, leaving characters’ fates open to us and a sense of underlying irrationality in the world at large.