Roger Ebert’s death prompted me to re-read his 1989 review of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. Ebert wrote the following of Lee’s most famous movie:

Roger Ebert’s death prompted me to re-read his 1989 review of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. Ebert wrote the following of Lee’s most famous movie:

It comes out of a weary urban cynicism that has settled down around us in recent years. The good feelings and many of the hopes of the 1960s have evaporated, and today it would no longer be accurate to make a movie about how the races in America are all going to love one another. I wish we could see such love, but instead we have deepening class divisions in which the middle classes of all races flee from what’s happening in the inner city, while a series of national administrations provides no hope for the poor.

In the context of late 1980s political culture, this was a superb reading of Do the Right Thing, especially in contrast to the response by most other white critics. It’s this context, and the white critic response to Spike Lee’s 1989 film, that I’d like to explore in this post.

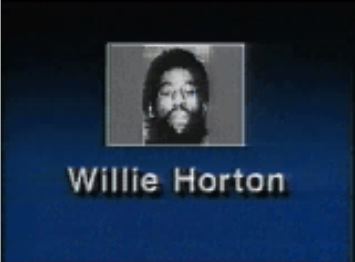

The rhetoric of national politics during the 1980s and 1990s testified to the stubborn significance of race, even after the civil rights movement and the Civil RIghts Act of 1964. Ever since Nixon leveraged “law and order” to help him win the presidency in 1968, throngs of politicians have used similarly coded messages about ostensible black lawlessness to great effect. In his successful 1988 bid for the presidency, George H.W. Bush benefited from a television advertisement that targeted his Democratic opponent Michael Dukakis by featuring a menacing mug shot of a black convict named Willie Horton.  While serving as governor of Massachusetts, Dukakis approved a weekend furlough program to help ease prison overcrowding. In 1987, having never returned to his Massachusetts prison cell from a furlough he was granted the previous year, Horton raped a Maryland woman after breaking into her home and tying up her fiancée. Bush’s campaign manager Lee Atwater, who joked that if he had his way American voters would think of Horton as “Dukakis’s running mate,” hung the albatross of black criminality around Dukakis’s neck. Bill Clinton, the Democratic nominee in 1992, studiously avoided such racial pitfalls. He took a tough-on-crime stance and supported capital punishment, arguing that Democrats “should no longer feel guilty about protecting the innocent.” Clinton accentuated this point during the campaign by returning to Arkansas, where he was governor, to witness the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a mentally incapacitated black man. In a similar nod to white voter solidarity, Clinton condemned rap artist Sister Souljah for a Washington Post interview in which she claimed the deadly 1992 Los Angeles riots were in some measure cathartic.

While serving as governor of Massachusetts, Dukakis approved a weekend furlough program to help ease prison overcrowding. In 1987, having never returned to his Massachusetts prison cell from a furlough he was granted the previous year, Horton raped a Maryland woman after breaking into her home and tying up her fiancée. Bush’s campaign manager Lee Atwater, who joked that if he had his way American voters would think of Horton as “Dukakis’s running mate,” hung the albatross of black criminality around Dukakis’s neck. Bill Clinton, the Democratic nominee in 1992, studiously avoided such racial pitfalls. He took a tough-on-crime stance and supported capital punishment, arguing that Democrats “should no longer feel guilty about protecting the innocent.” Clinton accentuated this point during the campaign by returning to Arkansas, where he was governor, to witness the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a mentally incapacitated black man. In a similar nod to white voter solidarity, Clinton condemned rap artist Sister Souljah for a Washington Post interview in which she claimed the deadly 1992 Los Angeles riots were in some measure cathartic.

“If black people kill black people every day,” she explained, “why not have a week and kill white people?” Speaking before Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition, Clinton compared Souljah to the notorious white supremacist David Duke, thus insulating himself from extremists and, more importantly, from Jackson, whose public support for Souljah was more evidence of racial division.

Powerful counterrevolutionary forces were bent on preserving the color line, in substance if not in style. The politics of crime confirmed as much. Since Nixon, the most successful American politicians have been those who have mastered the racialized language of “law and order.” As I’ve written about here, Rudolph Giuliani astutely leveraged white fears of black crime to become the mayor of New York City. In 1993, Giuliani won the first of two elections on the campaign slogan, “One Standard, One City.” As one pundit later wrote, this motto “implied that somehow black New Yorkers were getting away with something under a black mayor,” a reference to Giuliani’s foe, the incumbent David Dinkins. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, racial tensions flared in New York City to a degree unusual even by the levels of a city notorious for racial conflict. In 1986, as one of many examples, a group of white teenagers brutally assaulted three black men whose car had broken down in Howard Beach, a white ethnic enclave of Queens. One of the black men, Michael Griffith, was hit by a car and killed while attempting to flee the white mob. Widespread protests compelled even Mayor Ed Koch—not exactly beloved by black New Yorkers—to compare the incident to a lynching.

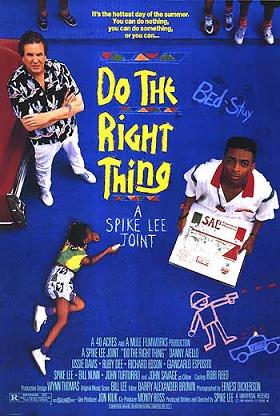

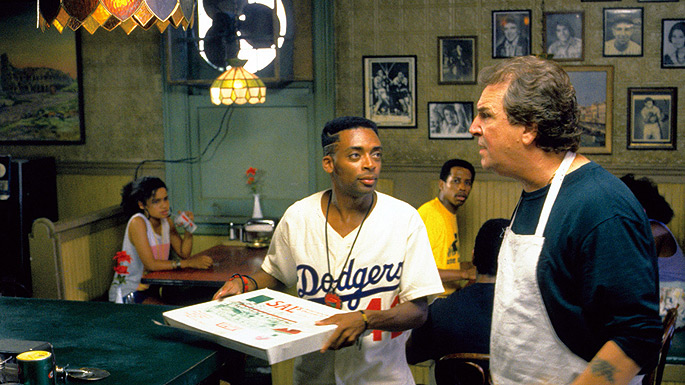

Such racial tensions were captured to perfection by Do the Right Thing, which Lee claimed he made as an explicit response to Howard Beach. The film’s story, set in a single block of a Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, takes place over the course of the hottest day of the summer. The two main characters are Mookie, an immature pizza deliveryman played by Lee himself, and Sal, the paternalistic owner of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria played by Danny Aiello. Mookie and Sal barely seem to get along even though they have mutual interests in maintaining a good relationship: Mookie needs Sal for employment and Sal needs Mookie as a liaison to his predominantly black customer base. Mookie and Sal’s tenuous bond represents the fragile state of race relations in New York City; when it splinters, festering racial tensions explode in violence.

Towards the end of the sweltering day, a fight breaks out in the pizzeria between Sal and a few of his black customers, including Radio Raheem, a proxy for Black Power who stalks the streets with his ghetto blaster cranked to Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.” When white police arrive at the scene of the melee, they kill Raheem while trying to subdue him with what Lee called the “Michael Stewart chokehold,” alluding to graffiti artist Michael Stewart’s 1983 death while in police custody. After witnessing Raheem’s murder, Mookie throws a trashcan through Sal’s window, setting off rioters who besiege the pizzeria, burning it to the ground. As police disperse the crowd with water cannons, the mob chants “Howard Beach.”

Upon first glance, the characters in Do the Right Thing come across as depthless racial stereotypes. Mookie, for instance, refuses to commit to his girlfriend Tina, a blunt Puerto Rican played by Rosie Perez, despite the fact that she is the mother of his son, thus rendering him a stand-in for black illegitimacy.  Sal’s son Pino, played by John Turturro, who hurls racial epithets with ease and frequency, personifies white ethnic resentment. Such cartoonish depictions reach an apex during a series of monologues in which several of the main characters rattle off a succession of base racial insults. And yet, despite the fact that most of Lee’s characters are caricatures, taken as a whole, his film is nuanced. Most of the characters, for instance, do the wrong thing—the film’s title is meant to be ironic—but not because they are evil. Rather, even when they do the wrong thing, such as when Sal calls Raheem a “nigger” or when Mookie destroys Sal’s storefront window, the characters evoke sympathy. They are responding to a set of less-than-ideal circumstances beyond their control. In the words of Ebert, one of the few mainstream critics who gave the film a favorable review, Do the Right Thing “comes closer to reflecting the current state of race relations in America than any other movie of our time.” It struck a chord with late-twentieth-century Americans conditioned to think about racial identity in zero-sum terms. Or, as Henry Louis Gates argued, “the film is an allegory of the melting-pot myth,” a parable for the pessimistic 1980s.

Sal’s son Pino, played by John Turturro, who hurls racial epithets with ease and frequency, personifies white ethnic resentment. Such cartoonish depictions reach an apex during a series of monologues in which several of the main characters rattle off a succession of base racial insults. And yet, despite the fact that most of Lee’s characters are caricatures, taken as a whole, his film is nuanced. Most of the characters, for instance, do the wrong thing—the film’s title is meant to be ironic—but not because they are evil. Rather, even when they do the wrong thing, such as when Sal calls Raheem a “nigger” or when Mookie destroys Sal’s storefront window, the characters evoke sympathy. They are responding to a set of less-than-ideal circumstances beyond their control. In the words of Ebert, one of the few mainstream critics who gave the film a favorable review, Do the Right Thing “comes closer to reflecting the current state of race relations in America than any other movie of our time.” It struck a chord with late-twentieth-century Americans conditioned to think about racial identity in zero-sum terms. Or, as Henry Louis Gates argued, “the film is an allegory of the melting-pot myth,” a parable for the pessimistic 1980s.

Unlike Ebert and Gates, most critics failed notice to (as pointed out by Jason Bailey in his Atlantic article, “When Spike Lee Became Scary”*) that Do the Right Thing was a profound meditation on American race relations. Instead, they worried that black audiences would interpret it as an incendiary call to arms. Newsweek‘s Jack Kroll described Lee’s movie as “dynamite under every seat.” David Denby, writing in New York, accused Lee of creating a “dramatic structure that primes black people to cheer the explosion as an act of revenge.” “If some audiences go wild,” Denby concluded, “he’s partly responsible.” In the same issue of New York, Joe Klein contended that Dinkins, who was running against Koch in that year’s mayoral elections, would “pay the price for Spike Lee’s reckless new movie about a summer race riot in Brooklyn, Do the Right Thing, which opens in June 30 (in not too many theaters near you, one hopes).” Reminiscing about Klein’s article more than a decade later, Lee asked: “What the fuck is that? What he’s saying is, ‘Pray to God that this film doesn’t open in your theater, because niggers are gonna go crazy.’” Klein thought Do the Right Thing had only two messages for black audiences: “the police are your enemy” and “white people are your enemy.” More astutely, Lee pointed out Klein had only two messages for his white readers: white property was more valuable than black life, and black audiences were too dumb to understand the difference between art and reality.

Do the Right Thing was destined for a controversial reception. White critics and audiences could not help but view it through a lens of black criminality—the same lens through which they increasingly viewed politics. That Ebert had a favorable review of Lee’s film is a great tribute to his work.

*Edited April 16, 2013 (It came to my attention that merely linking to the Bailey article, as I had done prior to this edit, was not a sufficient citation.)

9 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Great piece, Andrew. It makes me want to screen *Do the Right Thing* again. Because I was an ignorant small-town, small-minded nincompoop 18-year old when the film was released, I didn’t see the film until around 2006-07. I had already become a Lee fan courtesy of *X* and *Bamboozled*, but had neglected to catch up on the backlog.

I love how faux popular “art critics” consistently underestimate the power of art to provoke reflection and soul-searching. Reviews like Denby’s are actually evidence of their racist underestimation of black audiences. – TL

Great timing — I’m teaching this film this afternoon.

Excellent connection between Ebert and Spike Lee; I was not aware of this, and it helps me understand better all the celebratory obituaries about Ebert, whose pop line of criticism I never liked because of my artsy fartsy tendencies. It would be interesting to see what was Ebert’s analysis of Bamboozled; on one hand, white mainstream critics dismissed if not lambasted it for the most part, and on the other, it provoked intense debates among African-American critics and in academia. After Do the Right Thing and the documentary on Katrina, I think Bamboozled is Spike Lee at his most intriguing and ambitious, even if it is an uneven work of art. Sadly, Lee has quite a strong misogynistic and homophobic undercurrent in his films (She’s Gotta Have it, Jungle Fever, Girl 6, and Red Hook Summer are the most obvious, but this can be easily dissected throughout all his filmography). Also, the way he represents Latino-African-American relations is problematic, to say the least (aside from the Mookie-Tina relationship, see Jungle Fever).

I’m with you on *Bamboozled* being an underestimated film, and on being interested in Ebert’s review of it.

Here is the link to Ebert’s review of Bamboozled: http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/bamboozled-2000

He rated it fairly low since he believed that the emotionally charged used of blackface undercut Lee’s message.

Kahlil: Thanks for the comment. Yes, I’m aware of Spike Lee’s limitations (even though I don’t need my filmmakers to have my kind of politics). In fact, to be honest, I’ve never really cared for Lee’s films all that much. Partly because I find his characters one-dimensional. For this reason, I didn’t like “Do the Right Thing” the first time I saw it, or rather, when I watched it again about 5 years ago. But the more I’ve read about the film’s reception, the more I’ve thought about it in relation to the larger context of racial politics, and the more I’ve read interviews with Lee about how he conceptualized the film as a political intervention, the more I’ve come to appreciate what an accomplishment it was.

Two things have always struck me about “Do the Right Thing.” Visually, the film _screams_ parable. The bright colors set you in another world, and I never understood how one could argue that this film could touch off a real riot. Then again, Andrew does a nice job of filling in the context of the 80’s pre-1992 (anyone remember the similar freak-out over “Colors?”) making Ebert’s comments all the more insightful.

The other thing that strikes me about the film is how clearly Danny Aiello’s Sal represents white America. He denies he is racist. I even remember an interview in which Aiello said he did not see his character as necessarily racist. He comes across as kind for the first part of the film. And yet, when push comes to shove, what is the first word out of his mouth? “Do the Right Thing,” imho, captures America in an honest way that few films ever really get at.

Erik: Perhaps Sal is an “accidental racist”?

FYI: I slightly edited this post a week late because it was brought to my attention that merely linking to the Bailey Atlantic piece was not a sufficient citation. Chalk it up to the sloppiness that sometimes accompanies blogging.