A few weeks ago, I wrote a post about Rosey Grier, using his post-football celebrity career as a lens for looking at ideas and anxieties about gender and race in 1970s America. At some point I plan on carrying that line of inquiry up through the 1980s, as Grier’s “personal story” continued to mirror larger cultural currents.

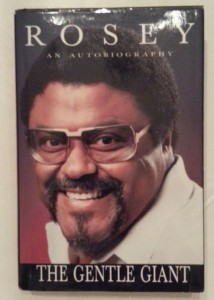

Most significantly, Grier’s embrace of “Born Again” Christianity in the late 1970s and his stance on “values” issues like school prayer and abortion led him to switch his party affiliation from Democrat to Republican after the 1984 primary. Grier’s political shift, which he discusses in his 1986 autobiography, reflected a dilemma facing African Americans who were committed to carrying forward the vision of the Civil Rights movement but who found the Democratic position on social issues increasingly at odds with the more historically traditional religious values of the Black community.

Most significantly, Grier’s embrace of “Born Again” Christianity in the late 1970s and his stance on “values” issues like school prayer and abortion led him to switch his party affiliation from Democrat to Republican after the 1984 primary. Grier’s political shift, which he discusses in his 1986 autobiography, reflected a dilemma facing African Americans who were committed to carrying forward the vision of the Civil Rights movement but who found the Democratic position on social issues increasingly at odds with the more historically traditional religious values of the Black community.

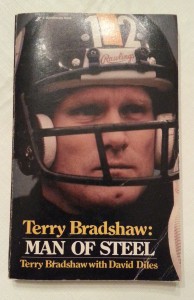

But before I follow up on that idea, I want to use this post to meander down a few rabbit trails related to sports celebrity, gender, and religion in 1970s America, rabbit trails I found crisscrossing through a text that has probably never before been considered as a potential source for understanding American intellectual and cultural history, and probably never will be again. I’m talking about that riveting read, Terry Bradshaw: Man of Steel (1979).

Bradshaw’s autobiography, co-written with sports journalist/broadcaster David Diles, was put out by Zondervan, the huge Christian publishing house that had just come out with a complete NIV translation of the Bible in 1978. I don’t have sales figures for the Bradshaw book, and I am not sure how I would find them. But the paperback copy I have in front of me – see the photo below– is from the second edition and the sixth printing. So Bradshaw’s story was at least selling well enough to justify repeated print runs.

As celebrity Christian testimonies go – and both Bradshaw’s and Grier’s autobiographies would belong to this genre – Bradshaw’s book seems a little weird. There are certain conventions that go along with “the testimony” or “the conversion narrative” in evangelical culture. This is particularly the case in the conversion narratives of the already converted – those subjects who grew up in religious homes, professing some faith since childhood, but framing that earlier religious experience as one of “nominal” as opposed to “genuine” faith. Grier’s autobiography follows this familiar model: I was baptized as a child, it didn’t mean much to me, later in life I hit rock bottom, someone talked to me about putting my trust in Jesus, and my life has been different ever since.

Bradshaw’s autobiography doesn’t really follow that line. It’s not linear in its narrative chronology, jumping back and forth between Bradshaw’s NFL career, his childhood, his college days, his Superbowl games, his interactions with the media. There are some interesting anecdotes from his college days, some post-game analysis from famous NFL victories and infamous defeats. In one chapter, titled “Confessions of a Crybaby,” Bradshaw relates with chagrin how he cried in the showers after a particularly difficult Pittsburgh loss (95). So much for “Free to be…” and Rosey Grier’s permission to grown men to cry.

Bradshaw’s autobiography doesn’t really follow that line. It’s not linear in its narrative chronology, jumping back and forth between Bradshaw’s NFL career, his childhood, his college days, his Superbowl games, his interactions with the media. There are some interesting anecdotes from his college days, some post-game analysis from famous NFL victories and infamous defeats. In one chapter, titled “Confessions of a Crybaby,” Bradshaw relates with chagrin how he cried in the showers after a particularly difficult Pittsburgh loss (95). So much for “Free to be…” and Rosey Grier’s permission to grown men to cry.

Speaking of Rosey Grier, there’s a very interesting aside in the Bradshaw book about the quarterback’s relationship to famous Pittsburgh defender “Mean Joe Greene.” In a short description that was quite clearly written by Bradshaw’s co-author, we find this observation about Greene:

“Mean Joe Greene” isn’t mean at all. His violence is the controlled type between the white lines of a football field. Off the field he is quiet and gentle (52).

Here again is the comforting stereotype of the powerful Black man as a “gentle giant,” his violence “controlled” and contained within the field of play. Greene has some interesting things to say about Bradshaw as a teammate, and these remarks are tossed into the not-very-smooth flow of the narrative along with everything else.

Indeed, there is no clear moment of any before and after in Bradshaw’s story, no once-was-lost-but-now-am-found epiphany, no decisive turning from an old life to a new one. This is a testimony in medias res: in the middle of Bradshaw’s religious ups and downs, in the middle of his professional career, and – bizarrely – in the middle of the dissolution of his second marriage.

Bradshaw discusses his then-current marital status in the last chapter of the book, “My Way, Her Way, His Way”:

By now the whole world must know that Jo Jo and I haven’t made an overwhelming success out of our marriage. We’ve talked openly about it on national television, and we’ve opened ourselves up in national magazine articles….No one feels lukewarm about me on the football field, and since Jo Jo and I have aired our problems in public, I have come to the conclusion that no one feels lukewarm about me in this matter either. The women’s libbers will all line up against me, and the good, down-home, old-fashioned women will be in my corner. As for the men, most of them will be for me, except for the handful who’ve given up the traditional male role (184).

Oh my Lord! When I read this passage, I literally fell out of my chair laughing. The gender typing is so extreme here it’s almost cartoonish. The women’s libbers! The traditional male role! Cue Anita Bryant. I mean, this is vintage 1970s; this is embroidered-bell-bottoms-and-butterfly-sleeves-jumping-the-shark-at-the-Ice-Capades 1970s gender wars language. That last bit about the Ice Capades is no exaggeration – Bradshaw’s wife, Jo Jo Starbuck, was a former world champion figure skaterwho was traveling with the Ice Capades when they met and married. Over basically the same time period during which Bradshaw was narrating his still-unfolding life story to his co-author, Starbuck was living in New York and performing with an ice show on Broadway.

Bradshaw continues:

Our basic problem is that I want my wife with me – I want her at my side, raising our children, putting our family ahead of everything except for our fellowship with God. I’m a down-home boy from Louisiana and that’s where I want to spend all my time when I’m not playing football for the Pittsburgh Steelers. Okay, I’m a male chauvinist! I said it, so you don’t have to. More than that, I’m not ashamed of being that! I think that for the most part, a woman’s place is in the home. Jo Jo had a career when I married her, and I never want to rob her of her identity and take away anything she’s worked and sacrificed to accomplish. But there comes a time – not only with figure skating but with football – when you should rearrange your priorities and get your house in order, so to speak, and start thinking about what you really want to do for the rest of your life….When I went to see Jo Jo in the show – well, it just killed me. It killed me because she was enjoying it so much. I didn’t want to hear how much fun she was having. What I wanted to hear was “Honey, I miss you so much. I can’t stand being separated from you. Let’s go to the ranch.” That’s what I wanted to hear, but I didn’t hear it….I’ve been ashamed of myself for some of the jealousy and resentment I’ve felt, but pardner, I’m open and up front about it. I love this woman. She’s gorgeous, she’s sweet, she’s kind, and most of all she’s a good Christian woman. I just want a full-time wife, that’s all. And in the final analysis, I don’t think that’s too much to ask (184-191).

Like I said, it’s almost cartoonish.

But it’s actually very serious, because Bradshaw’s self-described chauvinism is not some quaint and antiquated idea from the 1970s. His notions about the appropriate roles for men and women in marriage are current among many Americans today – as recent statements by Bradshaw’s former Louisiana Tech teammate Phil Robertson (of “Duck Dynasty” fame) have made clear. And it would be a mistake to assume that such notions are simply rural or regional phenomena, or that they reflect the views only of people who live on or hail from the economic or cultural margins of American society. I know plenty of solidly middle-class-to-affluent, educated, professionally accomplished men and women who hold this basic view of marriage today. Is this “cultural lag,” or is this just plain culture, complex and contradictory and ever contested?

And how is that contest faring since the 1970s? It is interesting that in their “celebrity testimonies” of the late 1970s and early 1980s, both Bradshaw and Grier had to address their marital history – a sign that, whatever their particular views about marriage and gender relationships, divorce was considered something that needed explaining to an evangelical readership. In his book, Bradshaw portrayed himself as the victim in his situation – the good, old-fashioned defender of family values who was abandoned by his selfish careerist wife. Grier, on the other hand, placed the blame for his failed marriage on his own selfishness and infidelity. In fact, after becoming a “Born Again” Christian, Grier eventually re-married his former wife – a perfect illustration, it would seem, of Christian values of repentance, reconciliation and restoration.

Bradshaw’s celebrity testimony in the years since Man of Steel has taken a somewhat different narrative turn. In this video clip from an interview he did for the 700 Club in 2008, starting at the 3:00 mark, Bradshaw discusses his history of failed marriages (he has been divorced three times).

As a Christian, Bradshaw said, “I had to figure out that it’s okay for me to fail, but I don’t want to be judged by you. And my friends back then judged me and were harsh with me.” The interviewer interrupts: “You mean your Christian friends?” Bradshaw continues: “Yeah. I had a hard time with that; I had a real hard time with it. And it ran me off, I got so angry with them.” This is not sounding like a promising direction for the kind of inspiring faith-based testimony that Christian groups might be looking for when they book Bradshaw as a speaker.

But then Bradshaw’s story finally reaches the requisite before-and-after moment that is the staple of the conversion narrative as a genre: “It wasn’t until ten years ago, Fathers Day, that I really got saved….I had one of those great, wonderful salvation moments….I learned that God forgave me. See, now you may not and they may not…but I know for a fact that God has forgiven me. So I should forgive myself. I’m not ashamed of who I am….See you can act it, but do you really believe it? And I know I believe it, and that makes me feel good.”

That this particular way of dealing with the presumably problematic fact of multiple divorces would fly with an evangelical Christian audience is interesting to say the least, and may indicate that even “traditional” cultural norms are shifting. I found that video clip on the website of Christian Speakers 360, “a Christian talent booking agency” that handles bookings for a number of current and former professional athletes, actors, and celebrities, not a few of whom have also experienced various marital problems or marital breakups while in the public eye. I don’t know to what extent these speakers address their marital troubles in their testimonies – I suppose it depends on the particulars of their stories and the audiences they are addressing.

The fact that a Christian interviewer in 2008 knew that an acknowledgment of Bradshaw’s troubled marital history had to be part of the discussion suggests that divorce is still something that “needs explaining” to an evangelical audience. But the notable presence of divorcees on the Christian speaking circuit, and the fact that Christian celebrities may be increasingly able to incorporate their all-too-human marital struggles into their own stories of grief and grace without losing credibility with Christian audiences — well, this could indicate that cultural norms about marriage are changing among evangelicals as well.

Or it may just indicate that celebrity (still) covers a multitude of sins.

9 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this post.

The intersection of evangelical Christianity and American sport is an interesting one. I believe it will provide plenty of fodder for present day and future historians of American sport. Think of people such as Tim Tebow, or Sam Bradford (QB for the Rams who’s also outspoken about his religious beliefs) in the NFL. The importance of evangelical Christianity to American society and culture is something that, I think, shows in the Bradshaw autobiography.

I’m also looking forward to hearing more about Grier and his political transition to the Republican Party. I’ve been doing a good bit of reading about the National Black Political Conventions of the 1970s, so I’m really intrigued to see Grier talk about his personal aversion to the Democratic Party’s liberalism on social issues. There’s some serious intellectual and cultural history left to be done about African Americans and conservatism after 1968. Grier’s personal turn is one window into that.

Thanks Robert. And I think you’re absolutely right about the productive possibilities of looking at sports and religion. I always think of Augustine bemoaning the rabid fandom of Christians cheering for their favorite charioteers. I suppose there may have been “celebrity Christian” athletes in late antiquity too.

I hope nobody gets the impression from this post that I don’t like Terry Bradshaw. I think he’s a hoot — probably my favorite Sunday commentator. I also think he gets a bad rap for being “dumb” — something he talks about in his autobiography, as well as in that film clip. I think he got typecast as a country bumpkin early in his career, but it’s not an apt read on him.

As to his testimony — well, that’s his deal. I just find it interesting that divorce is no longer a deal-breaker for someone’s ability to serve as a model Christian. (At least it’s not a deal breaker for famous rich white dudes who’ve won Super Bowl rings.) So for all that Bradshaw was grousing about the women’s libbers (!), he might owe some of his current status to their indirect/environmental influence on the (slowly? barely) changing mores of evangelical culture.

Finally, on being ready for some football — I don’t know about all y’all, but I am so ready for some football. Specifically, I am ready to watch my 49ers open a can of whoop-ass on the Seahawks tomorrow. I’m a historian, so I make no predictions. But I expect that it will be a good game. And just the thought that Jim Harbaugh might once again triumph over the execrable Pete Carroll fills me with almost unspeakable joy.

P.S. It occurs to me that Bradshaw’s language — “I know I believe it, and that makes me feel good” — may also be indirectly indebted to the subterranean success of “Free to Be…You and Me.” This is justification/sanctification recast as self-affirmation — though that shift probably started long before the 70s. I’m thinking at least as far back as Norman Vincent Peale — maybe even Aimee Semple McPherson.

Anyone have a thought on that?

Lora,

My first inclination when reading Bradshaw’s comments was to think of the varieties of Antinomianism that have emerged during the last five centuries. I don’t know if the various Christian groups have ever definitively hammered the last nail on the coffin for that maddening mental imbroglio, so maybe this is a never-ending conversation that actualizes whenever celebrities are given a bucket load of money for throwing a ball?

I also thought of the Latter-Day Saints and their appeal to the heart. When I was living in Grapevine, TX during the early 2000s, I encountered two Mormon missionaries at my apartment complex. They handed me some literature that sounded very close to Bradshaw’s phrase. I ended up visiting with them for a few weeks before they realized I wasn’t going to come to the nearby Mormon temple with them. Still, it was an invigorating experience for me (and hopefully for them). What I remember from their proselytizing was a refrain that centered on searching my heart accompanied by a warm, fuzzy feeling. If Joseph Smith’s message was true, I would feel a type of interior composure.

“I’m a historian, so I make no predictions. But I expect that it will be a good game.”

I’m going to be chewing on this distinction all night: Expect versus predict (Thanks for keeping me up past 3 am).

Yes I have a thought on that. It is all completely connected. I see it as a larger 1970s phenomenon. That is, the notion of the value of direct, unadorned and authentic feeling as innately virtuous in and of itself, connects a lot of inspirational 1970s literature, whether it be Christian or secular psychology and feminism. While those disciplines and beliefs might be at odds with each other on certain issues of content I see a unity in the sensibility of form, and in how the self is viewed. It is why a Wayne Dyer book, a born Again Christian book or an EST typed book have such similar tones and keep harping on the same refrains. I also believe it to be different from earlier 19th and 20th century literature in ways I can’t get into now. It is also extremely influential on the present time in ways that contradict the official message that the 1970s seems so far away and “dated.”

Mitch — thanks for using the word “sensibility”! That’s it exactly, of course. It’s not that Bradshaw says what he says today because of “Free to be…” or Peale or any text in particular, but all of it together as part of one big drift, so that even people who presumably share opposing views on things (Bradshaw and the “women’s libbers”) are moved on the same currents of self-actualization, self-affirmation, etc.

Mark — Hadn’t thought about the predictive valence of “I expect…” That’s an idiomatic expression for me, inherited from my grandparents, and interchangeable with “I reckon.” In fact, I had typed “I reckon” but decided to spiff up my language a little bit, so I used the equivalent (in my upbringing) expression. Why are they (rough) equivalents? Probably because they both point toward some level of wisdom through experience — e.g., if you reckon it is going to rain, that’s an expectation based on your long experience of reading the climatological signs. That’s your considered judgment, though you could be wrong. Farmers, it seems to me, have to do a lot of reckoning and expecting. Maybe historians not so much.

Added 7:39 AM But neither “I expect” nor “I reckon” necessarily carry any hint of futurity, at least as I’ve learned to use them. So I should have said that farmers have to expect/reckon about the future. Historians just have to reckon with / about the past.

It was late last night. After reading it again, I thought of one additional way I could read it: The first part, “I’m a historian, so I make no predictions,” might be translated as (in my mind): Since you’re talking about a football game, the assumption is that “predicting” or “a prediction” usually connotes/denotes the final score; that the concern with a prediction in this context is the numerical tally. The latter portion, “But I expect that it will be a good game,” might then point to the actual game itself; the playing of the sport as a process is what you might have been referring to.

But neither ‘I expect’ nor ‘I reckon’ necessarily carry any hint of futurity, at least as I’ve learned to use them.”

Have some farmers experienced that sixth sense regarding storms that animals seem to have? I think that’s why I equated the two, since, as you said, “they both point toward some level of wisdom through experience — e.g., if you reckon it is going to rain, that’s an expectation based on your long experience of reading the climatological signs.”

This is actually an interesting historical question to me. I don’t think I’ve ever thought about those two words in such a way. It might have been the unique way you framed the sentence (Aren’t you glad you refrained from using “reckon”?).

Aren’t you glad you refrained from using “reckon”?

I reckon so, Mark.

Alas and alack, “the execrable Pete Carroll” came away with the win in last night’s NFC championship game. However, as I expected/reckoned, it was a really good game, right down to the last play. The immediate post-game interview of Seattle cornerback Richard Sherman — a bracing moment of unscripted TV — instantly became a subject of conflict and controversy on the interwebs. Sherman’s interview certainly didn’t stick to the script of the “gentle giant” or the “controlled” Black athlete — which is, I think, at the root of a great deal of the controversy. But that’s probably a subject for another post. However, I’ll leave that to somebody else; my football heart is a little wounded after last night’s tough loss.

In brighter news, pitchers and catchers report next month. Go Giants!