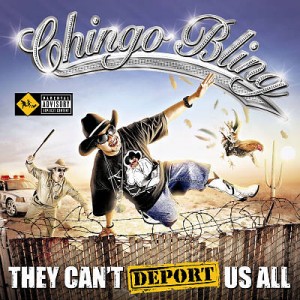

In Part 1, we drew attention to an important event: in 2007, Texas rapper Chingo Bling released the recording They Can’t Deport Us All. Bling’s record is a brilliant, inspired work of parodic agit-prop, rooted in the polyglot, underground hip-hop tradition of Houston. Promotions for They Can’t Deport Us All playfully modified the yellow, diamond-shaped signs that one often sees near the US-Mexico border—a haunting silhouette of an adult man, woman, and a female child (signified by flying pigtails), hand in hand, running (from what, and towards where?).[1]

As we noted in Part I, Bling’s aesthetic interventions struck a nerve. Billboards and promotional vans were riddled with gunshots. And recall Michelle Malkin’s comments of August 2007:

Understand this: The adoption of Chingo’s “They can’t deport us all” mantra is the adoption of a radically ruinous open-borders fallacy. Since we “can’t deport them all,” they argue, we should deport no one. To the likes of Chingo, national security concerns are a joke. Border Patrol officers are pigs. And jihad is a joke…[2]

It is unlikely that anyone has ever confused Michelle Malkin with a logician, but even according to the flexible standard against which we might measure her capacity for consistent thought, this is an odd series of statements. The oddness derives primarily from the fact that Chingo Bling is obviously correct: however parsed, “they can’t deport us all.”

In the next installment of this essay, we will try to take up the various possible meanings of “they can’t deport us all,” drawing on Jacques Lacan’s notion of the “pas-tout” or “not-all” and Alain Badiou’s reflections on this idea in his work on Intuitionist logic. We will want to emphasize the complexity of the phrase “they can’t deport us all,” a slogan that puts into question who “they” are, who “us” is, what it means to “deport,” and crucially, what “all” means.

Here, let’s take a look at some of the more obvious meanings of “they can’t deport us all.”

“Whites cannot deport all Latina/os,” or “the state, at the behest of whites, cannot deport all Latina/os”: this is perhaps the meaning that leaps to mind first, and, of course, Chingo Bling is correct. The operation “deport them all” is impossible. Surely Michelle Malkin knows that this is true.

Is what Malkin really enraged at the implication of Chingo Bling’s rallying cry: “They Can’t Deport Me” (signaled by the gleeful fence-jumping of the album’s cover art)?

Perhaps. There is a gleeful anarchic comedy about all this—the sort of thing that would drive anyone with a rage for order insane––as in a verse of the title track wherein Bling provides some family history:

Big Uncle Sam in that white and green van

Why you chased my daddy uh? Why you make him ran?

On the 25th of august 1969

Yeah, he crossed with a trampoline, not with a passport

The image of Chingo Bling’s father jumping over the border on a trampoline is a beautifully anarchic and comedic one, illustrative of the plastic force that meets the rigid policing fantasies of thinkers like Malkin when confronted by the vicissitudes of governmentality. “Controlling populations” across borders, it turns out, is a difficult business, at least when trampolines are lying around.

From a different perspective, the American state cannot deport “them all” because it quite literally lacks the repressive force for mass deportation (at over two million deported humans under the Obama administration, it is doing its best).

At the level of ideology, to complete the genocidal work of a defining a “them” against an “us” and ridding the country of every last “them” would be suicidal—achievable only as a structurally impossible paranoid fantasy.

Finally, most importantly perhaps, at the level of political economy, the system is working. Post-NAFTA, capital has come to quite like the situation of hyper-precarity and violence in Mexico, informal labor markets in agriculture and building trades in the US. American corporations profit from every aspect of the arrangement: systemic skimming of paychecks (either in the case of employers who suddenly disappear when the job is over or money-transfer and check-cashing services that charge usurious fees), and suppression of collective bargaining impulses under threat of deportation, not to mention the steady supply of narcotics to American consumers. In the randomness, unpredictability, absurdity of this state of conditional life, capitalism has found its new frontier of proletarianization—a particular form of sadism and discipline that discourages collective action and motivates moving on rather staying and fighting the epidemic wage theft, exploitation, and harassment experienced by immigrants on and off the job. “They” can’t “deport them all” because to do so would be to lose an extraordinary amount of money and to introduce a new level of risk and uncertainty into financial markets.

Thus, at the simplest level, what Malkin objects to is Chingo Bling’s illumination of capitalism’s obscene internal logic—if “they” all can’t be deported, though that would follow rationally from a strict anti-immigrant legalism, couldn’t we deport a few of “them,” at least?

I am lingering with Malkin because she distills the crucial logic at work in so-called “immigration debates,” the shared premises that link a Barack Obama to a Tom Tancredo. Chingo Bling offends Malkin because “They Can’t Deport Us All” secretly means: “Since we ‘can’t deport them all’… we should deport no one.” What all politicians, on all sides, agree upon is this: someone should be deported. We return to the logical operation conducted by Woody Guthrie in one of his most effective interventions, the 1961 song “Plane Wreck at Los Gatos (Deportees)”: wherein Guthrie names his friends (“Goodbye my Juan, goodbye Rosalita”) and contrasts this named-ness, what Levinasians might call a certain face-having-ness, to the anonymity of the official report (“the radio says they are just deportees”).

Part of the difficulty with immigrants’ rights politics—here, I should make clear that I am a partisan of a “no one is illegal,” or perhaps more accurately, “no one is legal,” line (as a co-panelist at a conference recently suggested), which is to say that I am for open borders and the immediate naturalization of all current residents of the United States––is that the Levinasian moment of recognition can become a substitute for the radical changes that a proper ethics of hospitality demands.

The given humanity of a “Juan” here or a “Rosalita” there might be acknowledged, then; a pardon granted, a conditional pass given. This remains, however, within the political-theological confines of old-fashioned sovereignty: the selective pardon (the more theatrical and publicized the better) has always been crucial to the operation of the state. In this traditional articulation of sovereign power, the one exception is granted in order to perpetuate the subjugation of the population as a whole. (In this sense, there is a tremendous resonance with the logic of carnival; both dynamics are interwoven in the ostensibly idiotic—it is the one time of year when one is commanded to get outrageously intoxicated––but secretly profound Jewish holiday of Purim, which happens at around this time of year).

What Chingo Bling achieves with They Can’t Deport Us All is an escape from this double-bind. I am going to suggest that They Can’t Deport Us All works is a way quite similar to Jacques Rancière’s key phrase “anyone and everyone”—more precisely, the notion of “the equality of anyone and everyone”––as the foundational term of democratic politics (with “democracy” a term that Rancière wants to insist remains a radical potential, not a name for Western-style parliamentary liberalism).

Malkin wishes to be able to deport “anyone and everyone,” which might also mean “anyone-as-a-substitute-for-everyone.” To be counted by authorities in a set that functions under the condition “subject to random attention/deportability”—this is what Malkin wants for darker-skinned people in the United States, because “national security concerns” and “jihad” are not jokes, though it is hard to see what they have to do with Chingo Bling in Houston, Texas.

Chingo Bling answers with They Can’t Deport Us All’s title track. The song begins with an ostentatiously ham-fisted guitar lick, looping over and over. It is the sort of “chicken-picking” figure (so named because of its rhythmic mimicry of the clucking of barnyard fowl, conjured forth by muted and choked notes) that signals a particularly Texan inflection of modern country in advertisements, soundtrack cues, cartoons.

Immediately, we ask: what is this figure doing on a hip-hop track? We quickly learn the answer: its function is cinematic, scene-setting. We cue up the album, expecting to enter the aural universe of Chingo Bling (to the degree we have expectations, let’s say that we predict certain spaces of festivity and enjoyment, certain evocations of Chicana/o life in the US Southwest, certain fantasy zones). Instead, we are immediately transported to someplace unexpected, to a site of hellish danger and ludicrous incompetence. The sonic mise-en-scene calls to mind Paredes and the sheriff who is “interpreted to death.” We are at the border.

Using an exaggerated drawl and growl, Bling assumes the role of white border cop: “bring out the guard dogs!” The track circles around itself via digital delay and echo. “There’s been an invasion!” “Yeah, you run!” Get ‘em boy, get ‘em!”

This intro prepares the listener for the arrival of the beat (with strong drum hits wedded to heavy metal power chord stabs, calling to mind classic Run DMC and Beastie Boys singles). Chingo Bling’s assumption of the role of Malkinian border authority is now refigured as anacrusis—retroactively situated as that which was to be interrupted by Chingo Bling the rapper. The fantasies set in motion by the country guitar loop (a certain set of scenes of Texas, beer commercials, trucks, the Alamo, line-dancing, what have you) are now subsumed beneath a question mark: the longer riff becomes a single note (along the way we are reminded of the intimate proximity of country and funk guitar styles)…

The song’s vocal hook accompanies the arrival of the beat: “They Can’t Deport Us All/We’re Gonna Knock Down the Wall” repeated over and over, delivered in Bling’s characteristically hushed, secretive, confidential tone. What happens next is remarkable. The anacrusis returns, but now totally altered. Chingo Bling’s hapless Texas lawman, red-faced and sweat-drenched (we imagine) now rants over the beat: “It’s been an invasion! That’s all we need now! Red Alert” (dogs barking)… Get ‘em boy! Y’all better hightail them on back to Mexico!”

Earlier, we considered Bruce Fink’s synthesis of Lacan’s notion of “scanding” as a procedure wherein “the analyst, trained to detect…rhetorical ploys, learns where to intervene in order to undo them,” and proposed this formulation as a possible answer to the question of what we are looking for when we say we wish to map a “politics of interruption.” What Chingo Bling is up to in “They Can’t Deport Us All,” I think, is exactly this: detecting rhetorical ploys, learning (and teaching) where to intervene in order to undo them. Perhaps it is this that makes Michelle Malkin so angry.

[1] See Leslie Berestein, “Highway Safety Sign Becomes Running Story on Immigration” San Diego Union-Tribune, April 10, 2005, for a fascinating story of the Caltrans graphic designer who came up with the sign. http://www.utsandiego.com/uniontrib/20050410/news_1n10signs.html

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Kurt,

Sorry if this was just a throwaway point you made, but I’m interested in hearing more about the connection between the sovereign’s power of pardon and the carnivalesque festival of Purim. I understand how a Bakhtinian reading of the carnivalesque connects to the pardon (suspending the ordinary rules of hierarchy to show that the power to suspend them remains solely within the power of the sovereign), but Purim is as much about the courage of Esther and the resoluteness of Mordecai as it is about the sovereignty of Ahasuerus. Most of the time, Ahasuerus’s sovereignty is being manipulated, either by Haman or by Esther, without him being fully aware of its ultimate ends. That is a far cry, I would argue, from the power of the symbolic pardon that you point to here.

Andrew–thanks for this question! What do I like talking about more than Purim?

So, the holiday and the megillah (Esther) itself is interesting in a couple of ways, in addition to what we have mentioned so far: “purim” means something like “lottery,” and the holiday is really about the *aleatory* from its name through its narrative (the narrative features you mention, I would argue, serve to bolser the representation of life as aleatory, random, subject to interruption). The other feature that isn’t always talked about is a mass-slaughter/revenge fantasy at the end. The only way this can be read as an ethical text, I think, is if we think of it as an allegory of the aleatory.

(I learned this interpretation, for what it’s worth, in Israel; I was there during Purim and one of our observant teachers presented it as a master-allegory about diasporic Judaism pre-Zionism, with Israel serving as the bottle stopper finally putting an end to the vulnerability of non-sovereignty… I now see the text as pushing towards a Judith Butler-ian rather than a Herzl -ian reading).

While I agree that the text has all sorts of fascinations (Esther means “I will hide” in Hebrew as well as echoing Ashtoreth, as Mordecai echoes Marduk), I think that the aleatory character of sovereignty, in its carnivalesque and pardoning-power modes, are paramount (there is even a recurring thematization of “the king’s two bodies”!).

Of course, you are right: the text is also about these particular epic heroes and villains. But would you agree that there is something about the command to get drunk and to blot out the iteration of the name “Haman” with the noisemaker something that touches on the question of sovereignty and power (I might say, the Real?)

Let me preface this comment as I should have prefaced the last by acknowledging the marvelous way you have deployed so many fertile connections and contrasts in this post, Purim being just one!

I definitely take your point about the aleatory nature of Purim, but I think we need to be a little more precise in defining what is the aleatory element. If my memory serves, the “lots” from which the name of Purim comes is in reference to a drawing of lots for which day Haman would execute his plans. The aleatory element is merely temporal; what is not aleatory is the nature of the threat to the Jews, which is constant (one might even say eternal) and comprehensive–it is not just a certain random percentage of Jews whom Haman would execute, but all the Jews within his jurisdiction. And, at least in the way that the moral of Purim is drawn, there will always be Hamans.

Therefore I would read the annual celebration of the holiday as a way that Jews reiterate that it is only the timing of the execution of the threat that is aleatory, not its existence. I would argue that the lesson proposed by the holiday’s celebration, indeed by the very actions you note, the drinking and the noisy obliteration of Haman’s name, is in fact an assertion of the ultimate inefficacy of temporal sovereignty, of anything like a reliance upon earthly sovereignty (or military might) for protection. Esther’s queenship is temporarily effective, but even the mass killings of Haman and his helpers is insufficient to extinguish the eternal threat which he symbolizes. The drinking and graggers are admissions of the flimsiness of the power of the Jewish people alone to fend off that threat. Perhaps the famous absence of the name of G-d in the Megillah is another way to note this message–a story of purely temporal deliverance can be told, but it has to be eternally retold because that deliverance is never permanent.

Perhaps that is what you mean, though, by a Butlerian reading of Esther?

Enjoying the Talmudic turn here. Chingo Bling as Esther?! Also lots and lots of goodies, such as your noting of the proximities of country and funk guitar styles (but presumably not their ideological affinities, or maybe so?).

I think the politics of interruption is a promising concept. But only if it is, as you start to propose, something more than just carnivalesque redux. Is this just “rough music” at the border, charivari with barbed wire and guard dogs (and some chicken picking), or something else, an interruption that (1) intensifies the contradictions of the ideology being disrupted or (2) resolves a “double bind” that the subaltern voices find themselves in or (3) both of the above?

Also thinking about interruption vs. collage, pastiche, certain Situationist tactics that make their way into punk, the seemingly useless (but maybe not?) protest of interruption in places such as congressional gallery seats (throw up your banner, shout a few words, get manhandled out by the police, carry on), and the tensions between interruption and civility.

More! I promise not to interrupt.

Best,

Michael

Thanks for this, so much. Yes, I agree, of course, the rupture of interruption has to be differentiated from carnivalesque repressive desublimation and “disruption” in its Arne Duncanian sense…

Interestingly, Butler’s Parting Ways has an awful lot to say about interruption and alterity, and may prove to be the really key text if “interruption” actually turns out to be a concept with which I continue.

Lacan’s Seminar XX of 1972-73, which I either will or won’t be blogging about on Tuesday (if not, certainly the Tuesday after next) also has a lot to say about “interruption”–as a very un-Bakhtinian notion, derived from set theory: interruption as the impossible’s self-assertion that prevents the “whole” from ever cohering.