————————————————————-

I.

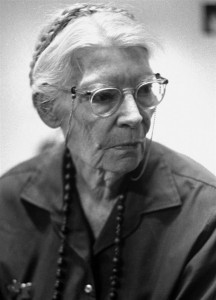

Catholic activist Dorothy Day (1897-1980) is best known for founding, with Peter Maurin, the Catholic Worker Movement. The Movement began in the early 1930s, growing out of Day’s long interest in labor and the laboring classes.

While the Catholic Worker Movement is less well-known today than it was at midcentury, it and Day’s name retained significance for Catholics well into the 1980s. I know of no pointed study of her impact or popularity, among Catholics and otherwise. But my sense is that her work and name became less important, or was transformed into something less jarring, as the “new orthodoxy” arose with conservative Catholics in the 1990s. That is not to say that First Things-style Catholics neglected or ignored her; her name has appeared in almost 70 FT pieces since 2000. Still, it is fairly intuitive that Day’s long and deep interest in labor would resonate more positively in an age when that topic was more central—when labor unionization was more prominent and labor was thought of as an important class of American society.

Day’s long connection with labor and her interest in class differences drew me to her writings. I was surprised, however, to also find in her works an interest in great books.  Indeed, after having given myself a long exposure to her thinking, especially through her 1952 book, The Long Loneliness, I will argue that Day both thought and operated with a great books sensibility.[1] In my view, the origins, development, and eventual steady-state of Day’s great books sensibility are more consistent, furthermore, with a bottom-up than top-down approach to the great books idea. Her sensibility was rooted in family tradition, journalism, and an intense practicality that correlated with her Catholic activism.

Indeed, after having given myself a long exposure to her thinking, especially through her 1952 book, The Long Loneliness, I will argue that Day both thought and operated with a great books sensibility.[1] In my view, the origins, development, and eventual steady-state of Day’s great books sensibility are more consistent, furthermore, with a bottom-up than top-down approach to the great books idea. Her sensibility was rooted in family tradition, journalism, and an intense practicality that correlated with her Catholic activism.

An exploration of great books sensibilities that purports to emphasize bottom-up versus top-down thinking, as this study does, must deal with the question of Dorothy Day’s place in the realm of thinkers and the history of thought. Whether one views that realm as a continuum or hierarchy matters less than understanding, in this case, the origins of Day’s sensibility. We can elide questions of her precise bodily and intellectual place, in her times, by exploring the place and development of her sensibility in history of thought. That said, I can accept both affirmative and negative arguments about Day as an ‘intellectual’. I find moments of complexity and systematic thinking in her writing that approach what many categorize as intellectual or philosophical. However, I also see something less complex and systematic, more along the lines of reflective and thoughtful. Those with rigorous definitions of what it means to an intellectual will probably find Day’s work unsatisfactory.

II.

Day’s interest in labor arose from her work as a journalist. For many years in the 1910s and 1920s she reported on labor, socialism, and communism. That was her first job after dropping out of college at the University of Illinois, where she had studied literature and written for the town paper. Her work as a reporter came in New York City, where she had followed her family after their move from Chicago in 1916. Her father was also a journalist. While in New York, Day wrote for the Call, Mother Earth The Masses, and the Liberator, but also freelanced. For a short time during World War I she gave up journalism to work in a hospital. But after the war and for much of the 1920s, Day traveled and changed residences for several years. Before returning to New York City in 1932 she had spent time in Europe, Mexico, Los Angeles, and Chicago (again—she had lived there as an adolescent and teenager). After returning to New York it became her home for most of the rest of her life.

Day’s interest in labor arose from her work as a journalist. For many years in the 1910s and 1920s she reported on labor, socialism, and communism. That was her first job after dropping out of college at the University of Illinois, where she had studied literature and written for the town paper. Her work as a reporter came in New York City, where she had followed her family after their move from Chicago in 1916. Her father was also a journalist. While in New York, Day wrote for the Call, Mother Earth The Masses, and the Liberator, but also freelanced. For a short time during World War I she gave up journalism to work in a hospital. But after the war and for much of the 1920s, Day traveled and changed residences for several years. Before returning to New York City in 1932 she had spent time in Europe, Mexico, Los Angeles, and Chicago (again—she had lived there as an adolescent and teenager). After returning to New York it became her home for most of the rest of her life.

Raised nominally a Protestant, Day became a Catholic in 1927.[2] This is significant because her previous time spent as a journalist coincided with a Bohemian lifestyle. That period included at least four serious love affairs, one marriage (and divorce), an abortion, and the birth of a child out-of-wedlock (with her daughter Tamar). Day became associated (and in some cases friends) with Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Kenneth Burke, Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Malcolm Cowley, and others. Day also participated in the Women’s Suffrage Movement. Day’s attitudes, experiences, and associates reveal her as either socialist or anarchist, but definitely as a leftist and something of a radical. I argue this despite her personal feeling that she “was not a good radical.” In relation to her conversion, she saw her moral trajectory as perhaps “the Baudelairian idea of ‘choosing the downward path that leads to salvation'” (p. 59). Despite those misgivings, she never disowned the politics or social justice of her pre-conversion work on, and for, labor.

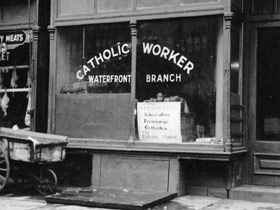

Dorothy Day met Peter Maurin in 1932, and they created the Catholic Worker Movement (CWM) a year later. Here’s how Catholic Workers describe their founding and movement to others (in 120 words, author and date of publication unknown):The Catholic Worker Movement began simply enough on May 1, 1933, when a journalist named Dorothy Day and a philosopher named Peter Maurin teamed up to publish and distribute a newspaper called “The Catholic Worker.” This radical paper promoted the biblical promise of justice and mercy. Grounded in a firm belief in the God-given dignity of every human person, their movement was committed to nonviolence, voluntary poverty, and the Works of Mercy as a way of life. It wasn’t long before Dorothy and Peter were putting their beliefs into action, opening a “house of hospitality” where the homeless, the hungry, and the forsaken would always be welcome. Over many decades the movement has protested injustice, war, and violence of all forms. Today there are some 223 Catholic Worker communities in the United States and in counties around the world.

When I noted above that Day and CWM were a midcentury phenomenon, the proof of that assertion is, to some extent, in the numbers. After creating the Catholic Worker newspaper, by the end of 1933 circulation hit 100,000. By 1936 it was 150,000 (p. 182). Circulation today is about 30,000 (per a December 2013 “Statement of Ownership).  Members of the Movement also created hospitality houses. The first was created in New York City in 1933. Per CWM’s website, “today over 130 Catholic Worker communities exist in thirty-two states and eight foreign countries.”

Members of the Movement also created hospitality houses. The first was created in New York City in 1933. Per CWM’s website, “today over 130 Catholic Worker communities exist in thirty-two states and eight foreign countries.”

III.

Day’s background in labor and social justice, and the size of the movement she created, is precisely what makes her great books sensibility fascinating. The lack of philosophical treatises and theoretical work, as well as her “narrow” interests (i.e. poverty, peace, labor, social justice), push Day out of the category of philosopher. She most certainly resides, however, in the broad category of intellectual because of her literary output and status as a “connector figure” or facilitator. This intellectualism—i.e Day’s capacity as an embedded intellectual or labor-inflected thinker (I won’t say Gramscian organic intellectual)—is tied up with a number of great books, all prominently mentioned and copiously referred to in The Long Loneliness.

In my next post I explore the contours of her labor-oriented thinking as it was braided with, and influenced by, her great books sensibility. – TL

————————————————–

Notes

[1] Every fact about Day referenced in this piece (that is not otherwise sourced) derives from Dorothy Day, The Long Loneliness (New York: Harper & Row, 1952; repr. with introduction by Robert Coles, New York; HarperCollins, 1997). Page references are to the 1997 edition. I refer to pages only for numbers and direct quotes.

[2] The timeline for Day’s conversion is confused in The Long Loneliness. To clear up my sense of chronology I consulted both CWM biographical timeline on The Catholic Worker website and her Wikipedia page.

10 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Tim, I hope you don’t mind if I share this, having mentioned to you on FB my fondness for Day and the Catholic Worker movement.

Here is a short list of titles about Dorothy Day and The Catholic Worker newspaper and movement some folks might find helpful. The FBI still includes the movement on its list of “domestic advocacy groups” that it believes necessary to keep tabs on.

• Coles, Robert. A Spectacle Unto the World: The Catholic Worker Movement. New York: Viking, 1973.

• Coles, Robert. Dorothy Day: A Radical Devotion. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1987.

• Cornell, Thomas C. and James H. Forest, eds. A Penny a Copy: Readings from the Catholic Worker. New York: Macmillan, 1968.

• Coy, Patrick, ed. A Revolution of the Heart: Essays on the Catholic Worker. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1988.

• Ellis, Marc. A Year at the Catholic Worker. New York: Paulist Press, 1979.

• Ellis, Marc. Peter Maurin: Prophet in the Twentieth Century. New York: Paulist Press, 1981.

• Ellsberg, Robert, ed. By Little and By Little: The Selected Writings of Dorothy Day. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1983.

• Forest, Jim. All Is Grace: A Biography of Dorothy Day. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2011.

• Piehl, Mel. Breaking Bread: The Catholic Worker Movement and the Origins of Catholic Radicalism in America. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1982.

• Roberts, Nancy L. Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1984.

Thanks for these! Happy to have the citations.

Ooops, I forgot to mention how much I like the photos!

Thanks!

Just wanted to comment on your point about Dorothy Day being a predominantly “mid-century” phenomenon. I went to a Jesuit High School in Akron, Ohio and I think both personally and in general that Catholic Worker was a huge part of our education. One priest in particular would take students every two weeks or so, and there was always a huge number of people gathered for the meetings of this club. Just getting on the sign up sheet to go was a really big deal. Probably you would also find it interesting that he spent a lot of his ministry in Latin America, particularly in El Salvador (this was an older priest, mind you), so there’s a good chance Day’s legacy today is bound up with Jesuits and proponents of liberation theology. Beyond that, I think the time is more than ripe for her legacy to have a big influence once more. Thanks for the post!

James: Thanks a million for the comment. I concede that my “mid-century” assertion is an impressionistic one. Even if I’m wrong, it’s entirely possible that her influence has changed or been modified, by Catholic parties and otherwise. My hunch is that Day’s legacy has been compressed by conservative Catholics to focus on her spirituality and conversion experience rather than her deep commitment to labor and her skepticism of Church hierarchy (evident on pp. 149-150 of the edition of The Long Loneliness that I use in the post).

That aside, any connection between Day’s (and Maurin’s) work and liberation theology would be worthy of exploration—whether direct or indirect (via citations, conferences, webs of influence, etc.). – TL

There’s no evidence, as far as I can ascertain, of a “connection” between the Catholic Worker movement and Liberation Theology, except insofar as the latter found sympathizers among already existing radical Catholics in this country, including later those in the Church hierarchy* articulating contemporary reflections and extensions of “Catholic social teaching,” much of which first appeared as a somewhat belated response (at the end of the nineteenth century) to communist and socialist doctrines and movements in the form of several papal encyclicals, and later was in part a response to developments in and the influence of Protestantism.

Of course Liberation Theology (its Central and South American variation) grew and flourished for a time in the socio-economic and political conditions of Latin American soil, although its theology was strongly shaped by those trained in European educational institutions who returned to their home countries and endeavored to put their theological learning and Catholic spirituality into praxis in a manner that spoke to the most urgent pastoral needs of the vast majority of Catholics in Central and South America (speaking of the ‘option for the poor’ Phillip Berryman notes that ‘Only the nonpoor can “opt for” the poor, that is, demonstrate preference for and solidarity with the poor).

The Catholic Worker newspaper has over the years accorded much space to topics on or related to Liberation Theology and some of its writers (from contemporary Catholic Worker movement soup kitchens or ‘hospitality houses,’ homes and farms) have of course drawn theological and political connections in the way of some similarities between Catholic Worker movement teachings and Liberation Theology. Yet I tend to believe the latter has (in significant respects) had more of an impact on Left-leaning or liberal Catholics to the extent that some its “demands” are not as arduous (e.g., communal living commitments, etc.) as those of the Catholic Worker movement (anecdotal evidence: I’m no doubt influenced by several relatives who’ve told stories of their participation in Catholic groups studying and teaching the ‘tenets’ of liberation theology amongst themselves), although there is little doubt that existentially and “on the ground,” there may be considerable overlap and similar real world consequences.

Finally, and with the late Penny Lernoux, we might speak of non-causal “connections” between the Catholic Worker movement and Liberation Theology and its (once flourishing) communidades de base insofar as both represent important developments within global Catholicism and a struggle for the “soul of the the Church,” a Church that under Pope Francis appears to be moving away from the regressive “Restoration” that sought to effectively erase more than a few Vatican II reforms. It is therefore distancing itself from a “Eurocentric and repressive Vatican” once defined largely by its barely concealed exercises of raw power on the order of Realpolitik as sanctioned and blessed by tortuous exegesis of Catholic dogma far removed from the ethical and spiritual substance of Jesus’ teachings as found in the Gospels.

*As evidenced in the two bishops’ letters from 1983 and 1986 on peace and the economy respectively.

The CW’s ties to Liberation Theology are explored in the following theses:

McKenzie-Hamilton, Joe, “To Afflict the Comfortable

and Comfort the Afflicted: Liberation Theology and the

Catholic Worker,” M.A. research paper, Fordham

University, 1996.

Smith, Matthew R., “The Catholic Worker Movement:

Toward a Theology of Liberation for First World

Disciples,” M.A. thesis, Christ the King Seminary, 2000.

Phil,

Could you elaborate on the meaning of “ties” in your reference to these MA theses: causal? sympathetic? homologous? solidaristic? etc.

I left out June O’Connor’s book above: The Moral Vision of Dorothy Day: A Feminist Perspective (New York: Crossroad, 1991), which I realized after looking her up to see what she had written (dimly recalling something) about Day and Liberation Theology:

“Her empathy for the working class and underclass of diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds enabled her to break through and out of the boundaries of [an] inherited identity [i.e., ‘a twentieth-century American woman with middle-class, Anglo-Saxon roots’]. As one who appreciated and chose to live with those who were without, she demonstrated the possibility of turning nonpossession, nonattachment, and lack of social prestige into strengths and virtues rather than causes for embarrassment or denial. Her work urges us to notice that people with possessions and status very often live in fear of losing these and that such fear constricts vision and generosity. Those without goods, status, and prestige have little or nothing to lose and thus are better poised to operate out of an ethic of sharing grounded in genuine caring. Indeed, Day’s vision and values anticipate those voiced in the liberation theologies of Latin America, Africa, and Asia: a decision to see life from the standpoint of the poor and to stand with the poor in a struggle for justice, and an approach to theology rooted in praxis, a view of religion as a spur to revolutionary action, a desire to help bring about the transformation of society grounded in values of justice, peace, freedom, and love.”