It is 1966. A twenty-five year old Bob Dylan stands, beanpole frame and electric curls illuminated under spotlights, between the instruments of rock ‘n’ roll and his audience of baffled and fuming folk enthusiasts. As Dylan’s one-time fans have done for the past year from San Francisco to Paris, the crowd is booing. “This is a folk song.” Dylan says to them. “I want to sing a folk song now,” he calls above the din. With the incantation “folk song,” Bob Dylan transforms the boos into roaring cheers and applause. “I knew that would make you happy,” he teases.[1]

My dissertation project began as an examination of mid twentieth-century scholars of mid nineteenth-century American literature, such as Perry Miller and F.O. Matthiessen. In the course of investigating the intellectual context of the scholars who created the first canon of American literature, I discovered a number of interesting characters who worked as social scientists in the burgeoning field of American folklore studies in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s. Cowgirls, frontiersmen, outcasts, mystics, Native-Americans, sons of immigrants, and daughters of slaves, these social scientists reminded me of the characters that populate so many of Bob Dylan’s song. As students, professors, journal editors, field workers for federal programs like the WPA, members of the American Folklore Society, or simply folk enthusiasts, they uncovered, collected, analyzed, and popularized tall-tales, superstition, myths, folk songs, and murder ballads. Often these folklorists were as unusual– both in their relationship to their context and in their temperament– as the characters in the songs and stories they recorded.

As a rising star in the Greenwich Village folk scene in the early 1960s, Bob Dylan drew upon the work of professional and non-professional folklorists who, in the decades before, had collected folk tales and recorded and published folk songs across the United States. Dylan was in no way unique in going back to the work of early folklorists. The 1960s folk revival in music grew directly from a lager folk movement in literature and social science, beginning in 1889 with the creation of the American Folklore Society, but gaining momentum and significance in the 1920s. I have become captivated by this story, and my dissertation has shifted focus. I now aim to examine the development of American folklore studies, and the broader folk movement that grew out of it, asking what cultural or political need early folklorists tapped into, and what they created that allowed the simple words “folk song” to mollify the hostile crowds at Dylan’s concerts in the United States, Australia, and Western Europe.

The quest to uncover American folklore represents a cultural and intellectual movement based on repossessing a hidden, repressed, uncanny American past. Neither modernist nor anti-modern, this cultural and intellectual tradition valued imagination and poetry over science, prized mystery over naturalism, and embraced a radical anti-historicist philosophy of history. Many of the early folklorists were women, Jews, African-Americans, Native-Americans, or others excluded from academic social sciences or from full citizenship in American society. They used this rich repository of hidden and unsettling stories about America to dissent from the dominant political culture, and they used the methods and tools of social science not to clarify, but to make the United States and American history more mysterious, more chaotic. Their work insisted on the existence of an alternative America where they could discover themselves.

Historians have argued that American social science grew from wide-spread commitment to naturalism, Progressivism, modernism, Protestant ethics, and Victorian sensibilities, but scholars who have produced valuable work on the development of professional history, sociology, economics, psychology and other similar fields, have not examined the American Folklore Society or the work of American folklorists as part of the discourse of social science.[2] Scholars such as John and Alan Lomax, Harry Everett Smith, J. Frank Dobie, Zora Neale Hurston, Benjamin Botkin, Constance Rourke, Carl Sandberg, and Dorothy Scarborough often considered themselves social scientists, but represent an intellectual tradition completely opposed to the modernism, naturalism, historicism, Progressivism, and Pragmatism that still dominates most characterizations of mid twentieth-century U.S. intellectual life.

Coming at the height of progressive history, the folklore movement also represented a challenge to the methods, goals, and assumptions of the history profession. Uncovering this movement represents a similar challenge to the historiography of this period, dominated by Richard Hofstadter’s The Progressive Historians (1968). As folklorist and song collector Harry Everett Smith wrote in the 1950s, “historical facts served hierarchy, while [folklore and folk tradition] was liberating because it grew from a voluntary personal response to the repertory of the past.” [3] Thus, in addition to offering a different view of the development of social science and its relation to U.S. thought and culture, this chapter creates a new canon of historical consciousness in the United States, examining figures critical of professional or progressive history.

I am also interested in the tension between individual and society that lies at the heart of the idea of “folk.” Although folk songs and folk tales often celebrate the unique individual, the outcast, or the criminal who stands outside society, much of the American fascination with folk grew from a desire to celebrate the culture of “the people” in the aggregate, and to put folklore to work in the service of political populism during the Popular Front and the Civil Rights Movement.

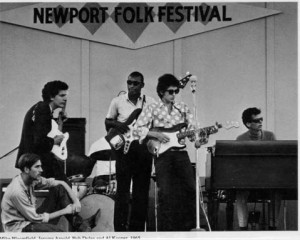

Bob Dylan (center) at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, when he first angered fans with his alleged betrayal of folk.

This tension between individual and society culminated in the conflict between Dylan and his fans. According to Dylan, folk music was “based on myth and the Bible and plague and famine and all kinds of things like that which are nothing but mystery.” Speaking of songs about “roses growing right up out of people’s hearts and naked cats in bed with spears growing right out of their backs,” Dylan asserted: “its all really something that nobody can touch.” Furthermore, Dylan separated the idea of folk from the politicized protest-folk song: “All those songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese, they’re not going to die. . . . Songs like “Which Side Are You On?” and “I Love You Porgy” – they’re not folk music songs; they’re political songs. They’re already dead.” Folk music, Dylan argued, was “too unreal to die.”[4]

Dylan’s conflict with his fans over the meaning of folk also points to one more important theme in the story of creating a canon of American folklore and the attempt to recover and reenact a certain American past: once a canon is created, how can it be kept alive and relevant? Once artists and thinkers have repossessed the past, how do they keep the past from possessing them?

I hope to continue to blog about these and other questions as I continue to explore the fascinating world of American folklore and the men and women who sought to uncover it.

______________________________________________

[1] Dylan then proceeded to play his newly released “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat,” which no one would describe as a “folk song.”

[2] See, Thomas Haskell, The Emergence of Professional Social Science (Baltimore: 1977); Andrew Jewett, Science, Democracy, and the American University (Cambridge: 2012); Wilfred McClay, The Masterless: Self and Society in Modern America (Chapel Hill: 1994); Dorothy Ross, The Origins of American Social Science (Cambridge: 1991).

[3] Harry Smith, quoted in Greil Marcus, Invisible Republic (New York: 1997), 100.

[4] Bob Dylan, quoted in Marcus, 114.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

very fascinating stuff here. I have worked a fair bit in the archives of some of the folklorists you discuss, and the overlap with the foundations of American Studies as a discipline is really interesting. You probably know Benjamin FIlene’s work, but if you don’t, it’s terrific; as is Sean Burns on Archie Green http://www.amazon.com/Archie-Green-Making-Working-Class-Hero/dp/0252078284 I will put in a plug for this new book on 78 collecting http://www.amazon.com/Archie-Green-Making-Working-Class-Hero/dp/0252078284 because it features a discussion of Ian Nagoski, the most interesting of the heirs to the Lomax/Smith tradition (and a public intellectual with serious criticisms of that legacy); and this great documentary on blues collector Joe Bussard http://www.amazon.com/Desperate-Man-Blues-Discovering-American/dp/B000JMK6IU

As luck would have it, our friend Michael J. Kramer is about as authoritative a voice on this history as I know about–hope he chimes in here.

It is worth thinking about, too, the way that Greil Marcus himself is self-consciously a product of Perry Miller/Leo Marx American Studies—he may well be, in fact, its most widely-read exponent.

oops, the book on 78s collectors is http://www.amazon.com/Not-Sell-Any-Price-Obsessive/dp/1451667051

Dear Rivka —

How exciting to read about your developing interest here in folklore studies in relation to mid-twentieth century US intellectual history, trends in social science, and the whole question of the “folk” in the midst of a modernizing, even post modernizing America.

One of the now mostly ignored facets of the so-called cultural turn in US history during the 1970s and 80s was Lawrence Levine’s argument in Black Culture, Black Consciousness that folklore materials themselves were untapped and extremely valuable source for tracing the past. Complex materials, to be sure, and not pure avenues into the minds of the “common people” in the past, but still quite rich, particularly for cultural historians who wanted to take ideas seriously as they appeared across a far broader range of the population. I think the debates among Levine, Lears, Lipsitz, Kelley, and Zemon Davis in the AHR from 1992 (an exchange that has surfaced here before) offer a nice window into the subsequent debates about how historians might access and analyze these kinds of sources.

But your post reminded me of something else that has always struck me as underdeveloped in US cultural and intellectual history (except in certain quarters, such as the aforementioned work of Benjamin Filene, as well as a few other studies I’ll mention below): a lack of attention not only to folklore sources themselves, but also to the methods and perspectives, the debates and controversies, within folklore studies as they developed in the 20th century in the US. The scrutiny in those fields to *how* to read sources, to relationships between power and culture, to issues of ontology and phenomenology as well as epistemology, to questions raised about assumptions concerning historical correlation and causality, to moments when incoherence of meaning mattered as much as hegemonic consolidation of ideas–I think there is still much for historians to learn here from those steeped in the methods and debates of folklore.

The field of folklore is also shot through with issues of class, race, gender, sexuality, region, nation, and world, of notions of free democratic culture and the role of the state in enabling or constraining it, and many other key analytic entry points into this wide-ranging story.

One way for historians to harness and make use of the methodological possibilities explored by folklorists would be to historicize more robustly the history of the field of folklore, and to do so in the ways you describe: by attending not only to the professionalization of the field (something Filene chronicles quite expertly in his chapter on Richard Dorson and Benjamin Botkin) but also to the broader intellectual, ideological, economic, performative, aesthetic, and artistic currents moving through folklore as a profession, a set of commercial and institutional enterprises, and a kind of “scene” or “scenes.” Maybe even as a Wickbergian “sensibility”! Or set of sensibilities.

One issue that your post raises already is precisely the question of professionalization. Folklore is marked more than any other field by a kind of anti-professionalization ethos. So many of the most famous folklorists existed on the margins of academia as it developed in the twentieth century. They had a foot, if not their entire bodies (both of self and of work), in bohemia. And their work, by focusing on “the people” and being framed by questions about the politics of culture, always pushed against, or at least was in tension with, notions of professionalization in terms of who possessed expertise, knowledge, wisdom, and the right to speak about it with authority. And, of course, the field of folklore itself has always been marginalized: is it merely some strange bastard child of anthropology (say it ain’t so!) or is it its own separate venture?

So I think there is a lot here to ponder. And there has been a lot of scholarship on the topics you raise worth diving into if you have not already. Benjamin Filene’s book is great. I use it in my folk music courses. But I think the one most pertinent to your questions is my teacher Robert Cantwell’s When We Were Good. Bob’s book is wild, deep, profound. But it rattles the cage of conventional academic writing a bit (I wish more intellectual history were written like this myself! It’s riskier prose, and sometimes it sacrifices clarity for adventurous metaphor, but it takes us away from what I find to be the stale formulas, and the stale thinking and assumptions behind those formulas, in a lot of historical writing). In fact, I’d love to see a whole exchange or panel at an upcoming USIH conference on Bob’s work–both about and informed by folklore studies, this kind of work might make a valuable contribution to intellectual history in terms of how we think about the relationship between culture and intellect and power both close up and across longer spans of time.

Greil Marcus’s work is important here too–quirky and often frustrating within the framework of conventional academic, and with plenty to critique within it, Marcus’s work comes out of American studies circa 1970 (as well as out of the countercultural bohemian folk revival milieu of the Bay Area) and it focuses quite a bit on the role of music in what you are interested in exploring, with a special sensitivity of course to Dylan as a cultural figure.

Indeed, I wonder as your project develops how you might address the intellectual history found in non-written forms: storytelling, visual arts, and since you start with Dylan, music.

There’s just so much to explore here the more you broaden your focus (and I assume you’ll narrow as this develops): the work of Constance Rourke and Joan Shelley Rubin’s study of her; the work of someone such as Alan Lomax, and John Szwed’s recent biography of him; the important and (still!) under appreciated folklore influence of the work of Zora Neale Hurston on professional folklore. Regional folklore efforts as compared to national ones and the interplay between them. Archie Green’s important lobbying in the 1970s to establish the American Folklife Preservation Act and Sean Burns’ recent bio of Green. Much more.

Now (oh, Didn’t He Ramble?), I offer a few corrections to your post, not in the spirit of nitpicking but rather in the spirit of us all getting this stuff right:

-Most importantly the quotation you have of Harry Smith, I don’t think those are his words. I believe they are Richard Candida-Smith’s sentiments in his amazing book Utopia and Dissent that Greil Marcus quoted to talk about Smith. Correct me if I’m wrong here, but I’m pretty sure that’s the case. Harry Smith would agree with those words, I suspect, but not sure he would have ever used language such as that.

-Carl Sandburg yes, not Sandberg.

-This isn’t really a correction, but rather a thought and question: I’d be careful to characterize Dylan’s fans as a unified group. There were many who objected to his going electric, but just as many who loved it. Indeed, it was precisely the controversy of his efforts to link conceptions of folk music to the emerging popular commercial avant-garde collisions of 60s rock *at the level of intellectual understanding rather than musical sound* that garnered so much attention. He was making an argument about what folk music was and might be in that historical moment, and making it *performatively* rather than in the conventions of either the emerging commercial niche market of “folk music” or in the academic or journalistic modes of the professional folklore field. He was doing so in dialogue with his fans, yes, but perhaps more so in dialogue/argument/rejection with what you start to characterize as the professional/commercial mix of those who had deemed themselves the keepers (gate keepers? flame keepers? depended on who you asked) of American folk by the 1960s.

OK, I have gone on long enough here. Hope some small portion of these musings is useful for you. And look forward to watching your project develop!

Folkloristically,

Michael

A few other wonderful contemporary thinkers on the history of folklore as a field who came to mind (there’s more of course):

-Neil Rosenberg and the writers in his edited collection Transforming Tradition.

-Anything by Roger Abrahams.

-Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett

-Nick Spitzer is better known for his great radio show, American Routes, but his writing about the folklore field is ace too.

-Julie Ardery’s amazing book on the “outsider” artist Edgar Tolson

-Regina Bendix’s book In Search of Authenticity: The Formation of Folklore Studies

-Rosemary Zumwalt, American Folklore Scholarship: A Dialogue of Dissent

-Jay Mechling’s work.

Hope this helps a bit.

Best,

Michael

Just wanted to say: thanks Michael for this illuminating discussion, and to Rivka. Looking forward to hearing about all of this as it evolves.

I really enjoyed this illuminating post as well as Kurt and Michael’s generous comments on folklore studies, a subject that also deserves more attention in Latina/o studies. Rivka, I look forward to all future posts on this!

I wanted to share my own bibliographic tidbit, a book I just read and thought is great for grasping the emergent circulation of notions of folklore, folklore studies, and culture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century: Brad Evans’ Before Cultures:http://www.amazon.com/Before-Cultures-Ethnographic-Imagination-Literature/dp/0226222640

Evans does a masterful job at complicating anachronistic notions of culture, looking at a broad array of ethnographic texts (from Joel Chandler Harris to to Sarah Erne Jewett and Dubois) while “suggesting how cultural difference might have been imagined without recourse to a culture concept.” There is much on folklore in the book, specially in the chapter on the Chandler Harris (author-collector of the Uncle Remus tales), John Wesley Powell, and the “folklore craze” in the late nineteenth century.

Folklore, news media, and propaganda all have a thing for each other. In those areas they overlap and form a blindness while allegedly struggling to shine light. It makes some of the history slippery. (Blind Willie McTell News, quoting “Bob Dylan In America”, by Sean Wilentz).

For an excellent analysis of the electric Dylan vs. folk music brouhaha, see Ellen Willis’ brilliant 1967 essay “The Sound of Dylan” I know it’s in Representative Men ed. by Theodore Gross.

I happen to think that “Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat” is a folk song. As David Lee Roth (yep that David Lee Roth) said: “Any kind of rock music is what I call high velocity folk music.”

Hey everybody’s good for something aren’t they.