Recently I came across a brief but very rich historiographic essay by Vincent Harding, “Power From Our People: The Sources of the Modern Revival of Black History,” published in The Black Scholar (Jan/Feb. 1987). Harding’s essay was originally delivered as a lecture during a summer seminar for college instructors hosted by the African-American World Studies Program of the University of Iowa. I’ll be discussing the essay today in connection with my own research, and my colleague Robert Greene will have more to say tomorrow about how the essay connects to his research interests.

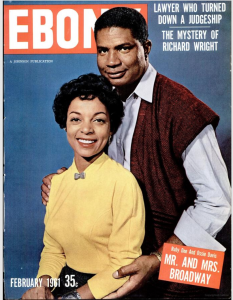

I found Harding’s essay in a search for scholarship that could speak to the significance of Ebony magazine in Black intellectual life. Specifically, I was looking for work that could shed some light on the role Ebony played in providing a forum for Afrocentric classicism or Afrocentric histories of Western civilization.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Ebony highlighted the work of Black historians and intellectuals like Leo Hansberry and John Henrik Clarke, who argued for the central place of African learning and cultural expression in shaping the intellectual legacy of the West, from the pre-classical period to modernity. This basic line of argument – that Western civilization was shaped from its very beginnings by intellectual and cultural influences from Africa (and Asia/the Middle East) – gained wide attention in 1987 when Martin Bernal published the first volume of Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization.* Indeed, some Black scholars saw in Bernal’s widely read and hotly debated book an unacknowledged or underacknowledged intellectual indebtedness to Black thought — very similar to the sort of unacknowledged intellectual indebtedness that Bernal was critiquing. “In this reading,” Jacques Berlinerblau wrote, “Martin Bernal figures as a sort of ‘Academic Elvis,’ watering down African-American traditions previously unknown to the mainstream, presenting them to a infinitely larger audience, and prospering handsomely for the replica he produced” (Heresy in the University: The Black Athena Controversy and the Responsibilities of American Intellectuals, 145-146).

While Afrocentric historiography was perhaps not widely known “to the mainstream” of American culture, it was certainly part of the mainstream of Black intellectual life, thanks in no small part to Ebony magazine. In his historiographic essay, Harding singled out Ebony for its crucial role in popularizing and passing down the work of Black historians, intellectual work that carried important political implications.

Harding described a flowering of Black history during the Civil Rights movement, and he emphasized how the demand for or interest in Black history was not a result of some “inner logic” of academic inquiry (as, for example, Bernard Bailyn claims for Atlantic history). Rather, the growth of Black history came from a grassroots desire for a usable past.

The resurgence of interest in black history, Harding wrote, “is not simply an academic happening. Indeed it was not primarily an academic happening as it began” (40). To be sure, Harding credited the students involved in the Civil Rights struggle, as well as the professoriate at historically black colleges and universities, for the rise of new Black history. “When the students moved into the struggle,” he wrote, “the black history they knew had usually come from those quiet, sometimes not so quiet, disciples and students of Carter G. Woodson who were teaching five, six, and seven different courses each week in the black colleges. Many of the black teachers would never write a book because of their course loads, would never have long bibliographies of their work, but often fed young people in the deepest parts of their spirits. What they did was much more important than long bibliographies” (45).

One of the crucial roles played by Ebony magazine was to bring that intellectual tradition, passed down primarily through classroom instruction or activist-organized community education seminars, to a readership many times larger than the audience that could be reached in a classroom. “It is impossible in my opinion to have any real appreciation of the significance and sources of the post-1955 black history revival without paying attention to the role of such periodicals as Ebony, Negro Digest (later Black World) and Freedomways,” Harding wrote. “These journals – outside of the academies, often scorned by the academies – have nonetheless been some of the most important guides and stimulants to and repositories of the modern black history revival” (48).

Many of the student activists protesting at Stanford in the 1980s were influenced by – and carrying forward – that “modern black history revival.” In my archival research, I have found that members of Stanford’s Black Student Union were making arguments that – read retrospectively – sound very similar to Bernal’s. But they were making these arguments in the early 1980s, well before Bernal’s book came out. While it’s possible that these students were drawing upon knowledge and texts that they had first encountered at Stanford – maybe in an anthropology class, or a classics course, or a course in African-American studies – I wouldn’t automatically assume that this is the case.

College freshmen are not tabulae rasae – they do bring ideas with them into the university, including ideas about history, ideas about a usable past. Many Black student activists in the early 1980s seem to have brought with them to Stanford the expectation that they would be learning more about the Afroasiatic roots of the classical world, upon which rested the idea of the West. As Harding’s essay suggests, there are several means by which this intellectual tradition, this usable past, was passed down within Black communities. So it is certainly possible — and perhaps even likely — that these students picked up these ideas because they grew up in families that read and discussed and debated the historiographic traditions they encountered in the pages of Ebony magazine.

——————–

*In this blog post – as well as in my dissertation – I am setting aside the question of whether or not Bernal was right in detecting racist underpinnings of the 18th-century historiographic turn in classical scholarship, a turn aimed at suppressing (Bernal argued) the influence of African and Asian thought on the classical world. A recent, riveting work by European intellectual historian Peter K.J. Park makes a very strong case that in the late 18th century “racist ideas and attitudes induced major revisions in historiography” among historians of philosophy (6). See Peter K.J. Park, Africa, Asia, and the History of Philosophy: Racism in the Formation of the Philosophical Canon, 1780-1830 (SUNY Press, 2013). I will have more to say about Park’s book in a future post.

12 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This is a great post. And I’m formulating a response to it right now–or, at the least, a similar meditation on Ebony magazine and Harding’s article about the publication’s importance to African American history. The importance of a usable past is key to understanding Harding’s point of view–and, really, most of African American historiography.

I know others will chime in here and to my piece tomorrow as well–but I just wanted to say, once again, great job. And thanks for reminding us of how much intellectual stimulation can be found in Ebony!

Excellent post, L.D. I look forward to reading more of your writings on the role of Ebony magazine in the larger story of the culture wars.

I think you and Robert are right on pointing to magazines (and by extension, newspapers) as vital, often overlooked sites for observing intellectual history in action. As I’ve posted on the blog before, my work on the NAACP’s The Crisis magazine first alerted me to the power of print culture, and current analysis of Freedomways/W. E. B. Du Bois is leading to equally rich discoveries. While there is tons of work yet to do on the broader history of the black press, the large number of African American newspapers and magazines offers a stunning variety of perspectives and opinions that capture both the leading voices of particular times periods as well as ordinary perspectives of everyday people. I look forward to further conversations on this topic.

I really enjoyed this–what a great find this historiographic essay is! You’re probably familiar with it, but Adam Green’s study of the Johnson publishing empire, Selling the Race does a great job of embedding some of these impulses toward African-American self-education within the local context of Bronzeville in Chicago. Based on my interests, I was immediately drawn to the fact that Harding delivered this paper at the University of Iowa, which makes me wonder what more could be said about regional variations within African-American intellectual culture based on the different geographical distribution of various kinds of institutions (e.g., most HBCUs are in the South while a lot of the “middlebrow” print culture comes from the Midwest).

Then again, there are certainly nationalizing influences going the other way as well–Ebony has a national circulation, after all, and graduates of HBCUs are found all over the country.

Yeah, that book is definitely becoming more and more important to my thinking about African American print culture in the 20th century. It’s one that more folks should also be talking about!

No Stanford connection, but Ta-Nehisi Coates touches upon some of this in his book, The Beautiful Struggle. His dad was involved with publishing and selling Afrocentric, Black nationalist histories throughout the 70s and beyond, and then wound up working at Howard, if I remember correctly, in the library. Coates was steeped in that literature throughout his youth. The memoir’s definitely worth checking out anyway, but it might help with context (or texture) on this, and I bet either he or his dad could be great interviews, too.

When I read that book years ago, one of the things I was struck by was just this–his father’s deep interest in African American education, history, books, etc. It’s something I could relate to–while my dad never had his own publishing company, he did certainly take me to black owned bookstores when he had the chance.

Thanks to all for the comments.

I want to thank Robert most of all for conversing back and forth about Ebony on Facebook and then by email, and for suggesting we collaborate on some posts. This scholarship stuff can get pretty lonely; it meant so much, and means so much, to know that something I am working on is helpful or important or even just possibly interesting for somebody else, and vice versa.

Thanks for the book recommendation, Andy. I will check it out. Indeed, the Harding essay is really good, but hasn’t been cited much. Two citations that I could find in the Thomson-Reuters database, four citations in Google scholar. It’s interesting how the essay models the tradition it explains — given as an address/lecture at a summer institute for teachers, it is a popularizing version of the historiographic essay. And it’s a really good historiography, I think — very valuable as a counterbalancing model against those “inner logic” narratives like Bailyn’s, where new questions or insights just naturally emerge from the work itself, rather than in dialog with or response to broader conversations happening outside the academy.

And yes indeed, Phillip, print culture is indispensable for following those conversations — in the case of my project, following the academic argument as it gets “popularized,” then showing how that popularized version of the story recoils back on the academy. It’s quite a feedback loop, and there’s no way to draw it without looking at what people outside the academy were reading and writing about it.

Zack, thanks for the Coates reference. Jonathan Scott Holloway (who was at Stanford during the period I’m looking at) mentions Ebony in Jim Crow Wisdom: Memory & Identity in Black America Since 1940, which will be reviewed here at the blog some time soon. These sorts of examples — much like the one Robert gave at the end of his excellent post — are really helpful for establishing in a general way that Ebony was part of the intellectual landscape for Black college students.

Great post, I really need to talk to you guys more! Final year doctoral student in UK, current title ‘Listen to the Blood: Ebony, Advertisers and the Boundaries of Popular Black History from King to Reagan’ – we have much to discuss!

That sounds FANTASTIC. Please by all means get in touch with me off the blog. Such a project, just from the title, sounds like something much needed.

James, thanks for the kind words.

I did a search for all the posts on this blog that mention Ebony magazine. Here are the results:

S-USIH posts mentioning Ebony

As you can see, to date we’ve had ten posts at the blog that mention Ebony (so we should probably make this a blog category and retroactively tag the posts for easier finding!). And as you can see from the post bylines, clearly we have Robert to thank not only for introducing Ebony into the discourse of the blog but also for initiating and carrying forward most of the discussions we’ve had about it.

In my current project, I am merely nodding to this subject in passing — barely making contact with a pitch I have to reach for to get a bloop single in one of my “innings,” one of my chapters. But Ebony is right in Robert’s wheelhouse for his current project, and I think he’s going to keep knocking this one out of the park. So I’m grateful to be included and take my cuts in a more wide-ranging discussion, but Robert is the heavy hitter on this subject.

(Have I mentioned that I love metaphors and baseball almost equally, and am never happier than when I can combine the two?)

Anyway, thanks again for the encouragement. It is most welcome and much needed.

And thanks for the kind words, L.D. I suspect this won’t be the last time we’ll see *Ebony* mentioned on this blog, heh.

Thanks for responses! I’m glad Andy Seal mentioned Holloway’s book, particularly within the context of recent developments around the Ebony Building at 820 South Michigan in Chicago, and the ways in which that building ties into Holloway’s arguments – The Johnson Legacy Project with Columbia College Chicago is really interesting, although it seems to have hit the rocks somewhat, along with the recent work of figures like David Hartt.

The personal relationship between Harding and Ebony’s Lerone Bennett is really rich territory for looking at Ebony’s role in the dissemination of black history out of the academy and black think tanks and towards a popular audience – Derrick White’s, ‘The Challenge of Blackness’ offers some great insights into how Bennett’s thoughts about black history were impacted by involvement with the IBW, which we can then trace through his own books on black history published during the 1970s (including a book which White takes his title from) and his special series of articles on black history published in Ebony during this period

My own understanding of the utility of black history to Ebony during the 1970s and 1980s really centers on black history as a kind of unifying prism through which contemporary debates about the black community(ies) and perceived ‘crises’ in African American life could be understood. We can take Johnson’s publishers statements in any number of special issues throughout the 1980s (I’m thinking in particular of the ‘Crisis of the Black Family’ special in 1986 as a good example of this) as a route into how this relationship was framed.

Its fascinating to see how advertising responses to the role and relevance of black history can be seen to shift during this period as well, which adds a whole different layer to Ebony’s content and coverage. Indeed, by the 1980s we can see a marked contrast between Bennett’s articles, which continued to call for the primacy of race and the importance of black history as a unifying historical experience, and advertisers which explicitly decreed that black history ‘belongs to everybody’ and used the black past to promote colorblind ideas about individual meritocracy and political rights.

Its really exciting to see people who are working on similar material!