On March 24-

On March 24-27 28, 2015, Indiana University Cinema and IUPUI’s Center for Ray Bradbury Studies are presenting a series of shorts and films based on Ray Bradbury’s work. The following essay is the first of two on Bradbury and intellectual history.

In a 1994 collection of Science Fiction writing, Ray Bradbury explained the germ of an idea that grew into one of his most famous cycle of stories (and arguably among the most significant for the genre), The Martian Chronicles. Bradbury said:

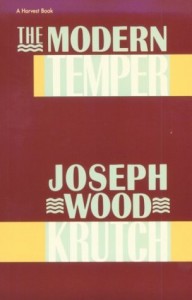

I imagine “The Off Season” was caused by my reading the critical works of Joseph Wood Krutch, one of the earliest ecologists, and seeing various issues of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar where the skinny lady models behaved outrageously in far places and outré climates. Seeing a Coca-Cola stand near the Egyptian Sphinx [illeg] pyramids further irritated me. These were the grains of sand which, popped into my oyster-mouth, caused me to grow a pearl—or, if not a pearl, at least a somewhat amusing tale about the first man to build a hot-dog stand on Mars. Once I dreamed up the man and the hot dogs, the story fell into place and was finished within that afternoon. I would like to think that Joseph Wood Krutch would have approved of it.

My colleague Jonathan Eller, Bradbury’s most prolific and celebrated biographer, explained that the character Bradbury conceived to set up a hotdog stand on Mars represented in the seemingly innocuous act the defeat of indigenous life in one civilization and the beginning of a culture that would sow the seeds of its own decline. If you don’t recall the narrative arc of the Martian Chronicles, Bradbury wrote a series of stories, most published in science fiction magazines in the late 1940s, that tells of the brutal and ultimately destructive impulses of us–we destroy all that we touch, including the earth and then, most likely, Mars. The settlement and development of our world leads to such catastrophic disasters that Bradbury has us search for a new home on Mars. The Martians try to resist only to succumb to earth-born diseases and stubborn earthly persistence.

My colleague Jonathan Eller, Bradbury’s most prolific and celebrated biographer, explained that the character Bradbury conceived to set up a hotdog stand on Mars represented in the seemingly innocuous act the defeat of indigenous life in one civilization and the beginning of a culture that would sow the seeds of its own decline. If you don’t recall the narrative arc of the Martian Chronicles, Bradbury wrote a series of stories, most published in science fiction magazines in the late 1940s, that tells of the brutal and ultimately destructive impulses of us–we destroy all that we touch, including the earth and then, most likely, Mars. The settlement and development of our world leads to such catastrophic disasters that Bradbury has us search for a new home on Mars. The Martians try to resist only to succumb to earth-born diseases and stubborn earthly persistence.

According to Eller, Joseph Wood Krutch helped Bradbury imagine that a hotdog stand on Mars was similar to what he saw in photographs of the commodification of another lost civilization, ostensibly Egypt. Eller writes in the first volume of his biography of Bradbury, Becoming Ray Bradbury, that the author, largely a self-educated polymath, “purchased a copy of [Krutch’s] The Modern Temper in January 1947″ helping to lay the intellectual groundwork for the novelette “–And the Moon Be Still as Bright,” “the story,” Eller explains, “that Bradbury would eventually transform into the fourth expedition chapter of The Martian Chronicles” (174-5). The crux of this part of the story is a tragic showdown between Captain Wilder of the spacecraft that has delivered a crew to Mars and Spender, a member of the crew who has taken it upon himself to stop the corrosive invasion of Mars by killing the rest of the crew. Of course, Spender’s attempt to prevent the madness of destroying Mars renders him mad by the Captain, and Spender is killed.

According to Eller, Joseph Wood Krutch helped Bradbury imagine that a hotdog stand on Mars was similar to what he saw in photographs of the commodification of another lost civilization, ostensibly Egypt. Eller writes in the first volume of his biography of Bradbury, Becoming Ray Bradbury, that the author, largely a self-educated polymath, “purchased a copy of [Krutch’s] The Modern Temper in January 1947″ helping to lay the intellectual groundwork for the novelette “–And the Moon Be Still as Bright,” “the story,” Eller explains, “that Bradbury would eventually transform into the fourth expedition chapter of The Martian Chronicles” (174-5). The crux of this part of the story is a tragic showdown between Captain Wilder of the spacecraft that has delivered a crew to Mars and Spender, a member of the crew who has taken it upon himself to stop the corrosive invasion of Mars by killing the rest of the crew. Of course, Spender’s attempt to prevent the madness of destroying Mars renders him mad by the Captain, and Spender is killed.

The paradoxical idealism of Bradbury illustrates why he was attracted to Krutch’s book. As Eller has said to me a few times, Bradbury saw rockets as both the delivery of destruction and deliverance from a broken world to one beyond the stars. In Krutch, Eller notes, Bradbury found an “articulation of a ‘tragic fallacy’ in modern man–that our appreciation of the great life-affirming tragedies of past literary ages disguises our inability to produce such works about our own age” (175).

Krutch and Bradbury seem apt observers for the discussion we’ve had (and continue to have) across many posts about the conditions that led to the Culture Wars. My own introduction to the work of Krutch came through my doctoral mentor Charles Alexander in his work, Here the Country Lies: Nationalism and the Arts in Twentieth Century America. At the end of a chapter that uses Randolph Bourne’s great turn of phrase, “This Hot Chaos of America,” Alexander calls The Modern Temper a “belated manifesto” of the Lost Generation that bemoaned “the moral and spiritual emptiness of the ‘modern temper.’ Modern man, according to Krutch, was unable really to believe in either the discredited older humanistic values or the ruthless, amoral prowess of triumphant science and technology” (150). Those “acids of modernity” had eaten away not merely at an older order but also at the prospect of finding something to replace it.

Bradbury’s consideration of Krutch’s lament produced an intriguing meditation on existential stewardship. Like Krutch, Bradbury didn’t pine for some idealized lost world of order and light; he wrote his characters as conscientious observers of and participants in dynamic worlds. They existed not only to demonstrate the dangers of technology without ethics but also to remind us that the past lives despite our plans to destroy it with our history.

The following piece of dialog that Bradbury wrote for the planned but never produced 1978 teleplay of The Martian Chronicles might capture what I mean. Captain Wilder tries to convince Spender that his plan to stop the invasion of Mars can’t succeed. Spender fought “a losing battle,” Wilder tells him. “You’ll grow old and die.”

Spender: Yes, but maybe Mars can take over again by then and protect herself. Feel. Out there. They’re watching.

Wilder: The dead Martians? Do you think they can feel us here?

Spender: Doesn’t an old thing always know when a new thing arrives?

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Interesting connections. I’ve read about Krutch in other contexts (particularly nature writing / environmental thought), and I’m curious to see how such ideas connect to popular culture.

May have to read Bradbury and check out how he (like, of course, Frank Herbert after him) applied ideas about commodities and ecology to exploration of a fictional desert…

“Mars can take over again by then and protect herself;” I wonder what other versions of ‘the planet (or ecosystem?) will protect itself’ sci-fi or other authors might’ve been exploring at the time?

Of all novel genres, my tendency with science fiction is always to think, or fantasize, that they are *the most imaginative* and least connected to everyday realities/context. The nice thing about posts like this (and others such as Robert Greene’s and Mike O’Connor’s reflections on Star Trek) is that they remind me of just how connected the works really are to the authors’ context. Even better is when one such as Jonathan Eller can show how a novelist is connected to other contemporary thinkers and larger philosophical problems of a day. – TL

I will use these comments to plug the Institute for American Thought at IUPUI. One of the discussion that circulates through that place is the role Ray Bradbury plays in it. Beside the institutional history that, because of Jon Eller, places Bradbury in the IAT, there are very good reasons to consider how popular culture and in this case science fiction fits into our study of American thought. With the work I do on movie history in America, I accept that place for popular culture in American thought, but also contend with the fights over how such culture relates to the more outright accepted pillars of intellectual history such as Charles Pierce and John Dewey, both of whom are represented in the IAT in different ways. In short, I find being part of the IAT an interesting chance to consider how best to leverage the fight over the role of popular culture in American thought.

Interesting way of framing the issue, Ray. I can see a consideration of “popular culture in American thought, as you’ve put it here, but also “popular culture as American thought” — not the whole of it, certainly, but definitely one expression of it. I guess the fight (or one fight) might be over the tension between those terms, “in” v. “as.” In any case, thanks much for this post.

Yup, well put. In fact, that distinction often seems to be in play within our field and among the various groups that write about and edit journals and books about American thought. For me, I often go back to the Randolph Bourne-Gilbert Seldes axis which seemed to suggest the necessity of playing with both in/as in order to understand modernity. I suppose we could call Nils Gilman on our bat phone?!

Enjoyed this post. I’m not that surprised that part of Bradbury’s reason for writing “The Martian Chronicles” was a response to American cultural and political trends. I only say that because there’s a long history of that in science fiction writing–as Tim, Ray, and LD all point out, it’s easy to tie together popular discourse through fiction to intellectual discourse during the same era.

A couple of examples: I’ve read elsewhere that H.G. Wells was inspired to write “War of the Worlds” partially by reading reports of European contact with the people of Tasmania. The alien invasion subgenre of science fiction has often served as a metaphor for concerns about invasion, war, and clashes after contact between civilizations different in technology and culture. I’ve wanted to write a post for some time comparing the 1953 and 2005 versions of “War of the Worlds” and what they both said about ideas of American security at the time.

Finally, reading this post brings me back to the Kim Stanley Robinson “Mars” Trilogy of the 1990s. It had some of Bradbury’s concerns, along with a more explicit warning about environmental degradation and the idea of starting over on Mars.