The Hunt County Confederate Memorial, located on the grounds of the Audie Murphy American Cotton Museum in Greenville, Texas.

As such, I’ve been frustrated by a number of what I will call “hold up!” articles, several from historians, because of a flawed line of alarmist-slippery-slope-questioning made explicit in this recent HNN piece: “So one question we should be asking is if we should be contemplating erasing history by deleting monuments from the landscape? Does that set a bad precedent? Where does it lead?”

The Star City Confederate Memorial is located at the southwest corner of the town square of Star City, Arkansas.

If we actually do learn a lot of our history from monuments (a dubious proposition worth questioning), what precisely are people gaining, knowledge-wise, from the massive numbers of Confederate ones, deliberately placed among the descendants of slaves and slave owners? What ideals and ideas are being conveyed by heroic renditions of Generals Lee and Stonewall Jackson, as well as other Confederate politicians and generals? The value of rebellion, treason, and war? The nobility of slave production? Freedom? Who’s freedom?

The removal of these monuments is, again, not about some insidious cleansing of history. It is rather a necessary revising of our shared history, much as postwar Germans and former Soviet citizens corrected their own public memory by toppling monuments to hate. So I’ll cast my lot with people like James W. Loewen, who is now taking stock (again), to paraphrase his most famous work, of the Lies America and its Monument Makers Keep Telling us. I’ll continue to annoy my friends and colleagues with calls for reframing, removing, defacement, and, yes, occasionally destroying the bad public art that keeps some of us in chains. – TL

13 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this Tim. I think it’s primarily about making an unequivocal stand against racism and slavery and its very real continuity in American society today. Letting these monuments stand as they are is supporting injustice pure and simple. No way around it.

Huzzah. This discussion about deleting or defacing history seems so contrived I have a hard time thinking something else isn’t going on with the objections. Because really, the solution is completely obvious – build a new one that condemns, not celebrates the Confederacy and its various heroes, or, put a fellow monument right next to it that explains, “look, this is how deeply racist America is, to put a monument to this in [insert date here]!” Or you know, just basically puts it in context and presents it the way that say, old relics from the Third Reich would be presented. Problem solved. No history erased; just the narrative it is telling brought closer to something not completely God-awful.

And James Loewen is at it again, with an HNN editorial, published today, that chastises James McPherson for neo-Confederate views in the latter’s recent textbook, The American Journey. – TL

I’ll admit I have qualms about destroying Confederate monuments; they may be historical artifacts in their own right. (They are, in effect, monuments to themselves as representations of white supremacy.) But that raises the question of what to do with a Confederate monument that can’t reasonably be (re)moved—does it just have to be demolished?

As I see it, there can be room for some creativity. The ultimate goal, I think, is not to remove Confederate monuments (though that may be the best method of achieving it) but to deconsecrate them. There may be various ways of achieving that.

See my comment, Jonathan. It’s solved pretty simply, although yeah, the possibilities for creativity are great, but the fundamental solution is really rather simple.

Simple yes, but I wonder who is going to add to the narrative as you suggest. I have made a similar call (and have even volunteered to contribute to the textual stuff) that has mostly fallen on deaf ears. With time and money factoring in this simplicity might become difficult rather quickly.

As an author of what Tim calls a “hold up” article, I would echo Jonathan’s point. I agree that that there are very good reasons to want to tear down memorials to individuals who led—or fought in—a war to perpetuate slavery and racial oppression. Although I tend to side instead with the idea of counterbalancing Confederate memorials with more accurate historical monuments (such as Charleston’s Denmark Vesey statue) as well as contextualizing markers, I have no problem with folks who prefer removal. (In that case, however, I would hope that we would preserve the monuments in some sort of museum or monument graveyard as can be found, I am told, in Hungary.) That said, I think that Tim’s essay, like several others that make a similar point, misrepresent the arguments of at least some of us crying “hold up!”

Confederate monuments do not tell us much—or, at least not much that is accurate—about the people they represent: the soldiers and statesmen of the Confederacy. But they do tell us quite a lot about the (disturbing) heroes, values, and culture of the people who erected them. They are, as Jonathan suggests, artifacts of the segregationist South and my worry about simply tossing all Confederate monuments in the trash heaps is that it might undermine our ability to understand Jim Crow culture.

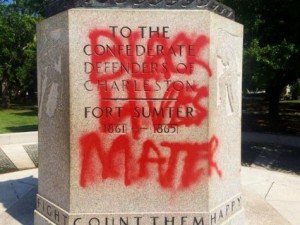

Well in that case, it seems to me like citizens with a can of spray paint are doing a pretty decent job very cheaply.

I am really fascinated by the push back against correcting “wrong” history. I would like to expand the discussion. Hopefully it will be of use.

Earlier this week, Eran penned a piece about utilizing settler colonialism to purge the influence of Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis in the study of early America. He could have just as easily have substituted Hartz or some other flavor of mainstream historical orthodoxy. I wonder what percentage of professional historians or other public intellectuals reflexively hold on to a triumphant “master narrative” of American history where forms of unfreedom are the exception. I am sure that the percentage is extremely high among laypeople. But even within the profession, how many would characterize the American experience as being predicated upon dispossession of native lands and the elimination of native peoples along with racial chattel slavery?

How many of us reflexively believe that slavery is in the past and not being practiced in the agricultural fields today? How many of us know what percentage of modern native households on reservations have electricity or running water? How many know when the Indian Health Service stopped performing forced sterilizations on young girls?

This push back against correcting wrong history is a kind of ‘historians anti-intellectualism’—a denial of consensus evidence (however ‘new’) that corrects the older master narratives. …I think I’ve just identified another strand in my long and ongoing research on anti-intellectualism. Thanks Brian! – TL

There is statue of Strom Thurmond outside of SC Capitol building, and it strikes me as really weird that in all this discussion of taking down Confederate flag and confederate monuments, there is no discussion of the monument to the guy who was major force in keeping politics of Confederacy/ “Lost cause” as important to 20th century politics.

Tom: I’m sure someone is thinking about this. But at least his descendants (granddaughter, I think, w/r/t taking down Confederate battle flag in SC) have been involved in more recent efforts to correct the record. – TL

I live in Hunt county and I haven’t seen the first monument in your article. It’s time I did. I grew up near the Star City monument shown above. I love Civil War history and the artistic monuments, both Union and Confederate. When I look at these pieces of historic art, I don’t think about slavery. I have ancestors who were confederate, yet owned no slaves (neither did most southerners). I agree with those of the slippery slope camp concerning where this will end. I personally don’t like statues of Malcolm X, a man who was a horrible racist, and separatist. Does that mean that they should be destroyed, removed, or worse, defaced? “the value of rebellion, treason, war”–might I remind you that the American revolution was a rebellion and considered by many to be treason.