Editor’s note: It’s my great pleasure to announce that Sara Georgini will be joining us for for a four-post extended guest-blogging gig starting with this post. She’ll be posting every other Monday. Sara is a Ph.D. candidate in American history at Boston University, and assistant editor of the Adams Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society, an editorial project that has published nearly 50 scholarly editions of the personal and public papers written, accumulated, and preserved by President John Adams and his family. Her dissertation, “Household Gods: Creating Adams Family Religion, 1583-1927,” is a history of faith and doubt in one American family, charting the cosmopolitan Christianity that the Adamses developed while acting as transnational agents of American politics and culture. She is a founding contributor to The Junto: A Group Blog on Early American History. You can hear some of Sara’s thoughts about public history and historical editing here and here. The following post is based on a paper she gave at this year’s S-USIH Conference. Please join me in welcoming her to the blog! — Ben Alpers

Nearly once a month, researchers contact the Adams Papers editors with a routine query: “I think I’m related to John Adams, and is there a way for you to check?” We check them all, starting with the printed genealogical tables of presidential families. Then we turn to the Adamses’ own family research, and review six decades’ worth of reference files. There, knee-deep in the glebe lands of Puritan England, I glimpsed the Cold War origins story of historical editing, and the public rise of modern American interest in the founders’ intellectual genealogy.

Nearly once a month, researchers contact the Adams Papers editors with a routine query: “I think I’m related to John Adams, and is there a way for you to check?” We check them all, starting with the printed genealogical tables of presidential families. Then we turn to the Adamses’ own family research, and review six decades’ worth of reference files. There, knee-deep in the glebe lands of Puritan England, I glimpsed the Cold War origins story of historical editing, and the public rise of modern American interest in the founders’ intellectual genealogy.

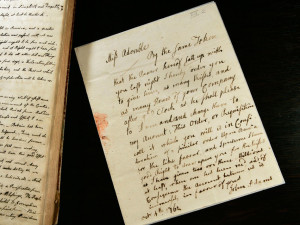

The Adamses’ hazy Anglo-Welsh heritage had drawn our first editor in chief Lyman H. Butterfield there, too, and so I waded through his offsite papers for clues. One stray, battered book in the cold-storage box caught my eye—a 5” x 8” black-ring binder that turned out to be a miscellany or “rubbish” book kept by Butterfield to document his first year on the job. Mining the words of revolutionaries like John and wife Abigail for mass consumption in 1954 was, Butterfield wrote, “the greatest opportunity of its kind ever presented” to an editor. His task was epic: to prepare nearly 250,000 manuscript pages for publication, while upholding the twin goals of preservation and access. Toiling away with a small but hardy crew at the Massachusetts Historical Society, Butterfield faced the founders, and nearly fled. Transmitting early American ideas to the modern public was, he wrote, a “heavy responsibility” for any historian to undertake. “How,” Butterfield asked, “can I hope to live up to it?” The depth and heft of John and Abigail’s rich correspondence—some 1,200 letters, minutely edited when first printed to suit Victorian sensibilities a century earlier—convinced him to try.

At Princeton’s Papers of Thomas Jefferson project, Julian P. Boyd faced a similar wealth of content. So, too, did Leonard W. Labaree at Yale’s Papers of Benjamin Franklin. Armed with a critical mass of primary sources unearthed from attics and archives, these historical editors successfully promoted manuscript preservation in the nuclear age. Flanked by federal support in the form of the National Archives, and by what became the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, they ensured that rare books, alongside cutting-edge defense needs, made it onto the Congressional docket. With President Harry S. Truman’s support, the first scholarly editions of the founders’ words went to press. Conceding that a “recital of the Adams legacy is surely intimidating,” President John F. Kennedy welcomed the initial volumes in his American Historical Review essay of January 1963. “We can expect to have a genuine historical chronicle, not mere biographical vignettes,” Kennedy wrote approvingly.

Postwar public historians like Butterfield aimed to fulfill the mission of the new(ish) National Archives: to “seed our national consciousness with historical fact.” One way to do that was to let loose the founders in print: Hear Adams argue; see Jefferson write; let Franklin charm. The unique cadre of historian-archivist-editors forged a fresh version of the founders’ words—one that fostered lively intellectual debate, and at least one best-selling musical/movie. As the “life in letters” model of 19th-century biography ceded to modern editions, Butterfield and his peers drove cultural interest toward the production of high-quality public history. It’s what people seem(ed) to want. Postwar Americans responded favorably to the publication of candid, prickly John Adams’s diary. They connected with mother Abigail’s unspooling memories of a homefront at war. Even the nation primping for a Bicentennial gala paused, intent to reexamine the roll of what (or who) was listed as bought and sold in Jefferson’s Farm Book. The complexity of editing founders’ half-told lives disrupted traditional history-writing and reshaped archival practice, at a critical moment in postwar American intellectual life. In reintroducing early Americans’ experiences, sins, and contributions, these historical editors reoriented the scope of scholarship and tradecraft at midcentury. Or, as Butterfield’s friend, the modernist poet and Librarian Archibald MacLeish, put it over cocktails in Cambridge one night: “Tell me, is the work you are doing going to set a new magnetic north in American history?”

Artfully, Butterfield dodged the query. After all, role models were few. When Philip Hamer defined the new breed of scholar-editor in his 1961 presidential address to the Society of American Archivists, the list thudded with heavy qualifications. Per Hamer, the modern editor exhibited the “humanity of a biographer, the flashing insight of a poet, the dedication of a teacher.” He was generous with time and knowledge. Finally, he must be “indifferent to, or at least resigned to, small financial rewards.” Butterfield’s C.V. was robust: a master’s degree from Harvard, five years’ service at the Jefferson Papers, and an enviable post as director of the Institute of Early American History and Culture near Colonial Williamsburg. He published a compilation of Benjamin Rush’s letters. He taught at Harvard, Franklin and Marshall College, and at the College of William and Mary. Yet the idea of editing John and Abigail Adams made even a veteran editor nervous. “The founders,” in 1954, retained a near-mythic status. If Americans felt “related” to Adams or Jefferson at all, it was mostly sentimental: the founders’ original words were, for the most part, still walled away in private archives. Butterfield and his peers sought to change that, to make the founders familiar enough to provoke new research.

Butterfield’s editorial apprenticeship with Julian Boyd proved a huge source of support. Boyd had lobbied Truman to fund publication of the Jefferson Papers. His editorial skill, evident in his scrutiny of Jeffersons’s drafts of the Declaration of Independence—and the marathon pace of production that he set, shuttling off 16 volumes between 1950 and 1959—was unparalleled. Boyd was agile in the archive, and with the press. When the first Jefferson volumes appeared, national newspapers ran the story on page one. The sage of Monticello was rediscovered, reified. Headlines ranged, but the broad fascination with resurrecting 18th-century personality spoke to the bitter sectarian politics of the day. Jefferson, under 1950’s hot lights, became a rural Virginia homebody who corresponded with “great men and humble citizens” alike. In lighter moments, magazines like Life replayed his diplomatic tours. One glossy spread even invited suburban Americans to tour French wine country “through Jefferson’s eyes.” And, as with scholarly reviews of other documentary editions, academic journals met the projects with thorny praise. Operating minus a cumulative index, most reviewers lauded Boyd’s approach to Jefferson as a cosmopolitan patriot tailor-made for the Cold War era: a man of science, liberty, and law.

Producing modern volumes with clear, authoritative transcriptions was a stride forward. The real revolution of historical editing came with the modern union of preservation and access. No longer were Jefferson’s Declarations or Abigail’s accounts to wither, proudly, in a secret archive where dissertators could not reach. Historical editing, at midcentury, offered a new cultural site for intellectuals and their publics to convene, over the common cause of telling the nation’s story. Butterfield, Boyd, and Labaree were key architects of that vision. American archives, by association, were open to all, and that included the Adams Papers. Since the 1870s, most of the Adams documents resided in the fireproof Stone Library, built by Charles Francis Adams near the Old House in Quincy, open only to a select few. Once moved to the Historical Society on deposit in 1902, the papers remained a kind of hidden history. Locked away in a sunny seminar room, the Adams archive was notoriously difficult for researchers to explore. Between 1908 and 1920, Worthington C. Ford remained the sole editor with access and publication rights. Butterfield’s first thought was to organize and open the papers for research.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Butterfield was caught up in the excitement of a new public history that established visitor sites like Plimoth Plantation and Colonial Williamsburg. He was keen to preserve a “national treasure house” of manuscripts, while unlocking it for study. Butterfield created one long chronological sequence for the general correspondence, to be filmed on 608 reels. Originally, he estimated that 125,000 to 150,000 pages of paper prints were needed. A reconnaissance trip to the Library of Congress, where he watched archivists filming the Papers of the Continental Congress, persuaded Butterfield that 1) the new machinery held real merit and 2) technology had reshaped the archivist’s role. Butterfield remained the scholar’s greatest ally. To advisors, he “pleaded for liberality,” anxious that “scholars cannot make more than token use of the material.” When he wasn’t reading Adams documents, he scavenged the local biography shelves for Patton, Truman, and more. He juggled camera crews from CBS and Life magazine.

Part of preservation meant rethinking the standard architecture of an editorial apparatus: how documents were selected for publication and which types mattered most; where annotation called out archival silences; whether the index should be names-only or analytical in nature. There was no shortcut. Butterfield read as much as he could to understand the Adamses and the way they wrote down history. Butterfield readied an editorial plan. He envisioned two series: diaries first, then family correspondence. He planned a third track, focused on the papers of the three Adams statesmen, which “would take the longest time to plan and be the hardest editorial chore.” Annotation was to be minimal, elegant, direct. He hoped that a collected index would allow scholars to search across multiple volumes. By providing faithful transcriptions of original text, Butterfield and Boyd now offered unfettered access to the founders’ many turns of thought.

Butterfield read Adams manuscripts seven days a week, conscious that the Victorian editions no longer fit scholars’ needs. In 1955, he sat on a panel at the American Historical Association with his mentor Boyd, aptly titled “Publishing the Papers of Great Men.” The guild was in transition, Boyd lectured, ready to cast aside the arcane editorial rites that omitted “family matters” and “cleaned up” original text. Raw manuscripts, he argued, made for refined history. Boyd told conference-goers to weigh how they made colonial ideas accessible to a new, critical audience. “We ask a great many more questions of our texts than our predecessors did,” he said.

Libraries champion many publics. Archival dilemmas like Butterfield’s and Boyd’s deserve a place of analysis within American intellectual history. “We can spread the record before the world,” Butterfield wrote, “to be read, understood, and in some degree, emulated.” The founders’ “relatability” was/is why they are quoted, misquoted, and even retweeted today. When we consider claims about the founders’ intellectual genealogy, it’s worth discussing why this revolutionary cohort can feel so familiar—or foreign—to modern minds. What is it, tucked away in their words, that makes them seem so oddly “relatable”? Butterfield’s survey of sources, and Boyd’s appraisal of audience hints, too, at a greater democratization of intellectual authority in postwar America. In an era when research dollars poured into atomic energy or jet propulsion, Adams and Jefferson editors invoked paper recordkeeping as a vital tradition, and one with a long future in the computer age. Working as a scholarly collaborative, they convincingly staked the public interest on sharing 18th-century sentiments, even as they tightened the canon for those seeking “founder” status. On Bicentennial’s eve, scholars pondered the cultural “turn” ahead. John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin offered complex prototypes to study. Still, historians longed to move past “Publishing the Papers of Great Men.” Abigail led the way.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Welcome, Sara. What a marvelous post — and it ends on a cliffhanger!

I’m particularly interested in how the importance of preserving “the originals” guided/constrained the development of this broad publishing endeavor. Your mention of Butterfield’s enthusiasm for using the latest technology (microfilm, in that example) to open up these documents for scholarly research reminded me of Nicholson Baker’s Double Fold, and of (he argues) the profound loss to scholars that came from the conviction that the “originals” (historic newspapers, chiefly) either need not or could not be preserved — or, at least, that preserving them would be too expensive.

By contrast, the hand of the founders — both their talismanic touch and their script on the page — makes it inconceivable that their papers would be transposed to another medium and then discarded. But I suppose that might be true of any archival manuscript collection — publication of scholarly editions does not render “the original autographs” irrelevant. Perhaps it makes them all the more important.

Looking forward to reading more!

Thanks, L.D. and all, for the warm welcome. Also, a general huzzah for the many cliffhangers we study in early America!

Yes, I had a similar soundtrack running as I wrote: Miles Orevell’s “The Real Thing,” on the debate over imitation and authenticity. Maybe another look at archival dilemmas like this one might pose a useful sequel.

Welcome, bravo, and hooray, another Documentary Editor! I look forward to your upcoming posts.

Thanks, Ethan, glad to be here!