Editor’s Note: This is the last of four biweekly guest posts by Sara Georgini. — Ben Alpers

Rain hammered his manuscript. Ink pooled over the words that a weary John Quincy Adams, 76, had polished at four o’clock in the morning for his Cincinnati crowd. In a lifetime of travel, this had been a particularly tough trip for the ex-president to make. Leaving Boston in late fall, Adams looped west through Albany and Buffalo. Snow crusted the rails near Utica. Hail kicked at his train window. Icy wheels skidded along the patches of newish track; he ticked off miles in his omnipresent diary as they jerked and skated past. Pausing at a Cleveland barbershop, the elderly Adams was mobbed, in mid-shave, by a corps of western well-wishers.

Rain hammered his manuscript. Ink pooled over the words that a weary John Quincy Adams, 76, had polished at four o’clock in the morning for his Cincinnati crowd. In a lifetime of travel, this had been a particularly tough trip for the ex-president to make. Leaving Boston in late fall, Adams looped west through Albany and Buffalo. Snow crusted the rails near Utica. Hail kicked at his train window. Icy wheels skidded along the patches of newish track; he ticked off miles in his omnipresent diary as they jerked and skated past. Pausing at a Cleveland barbershop, the elderly Adams was mobbed, in mid-shave, by a corps of western well-wishers.

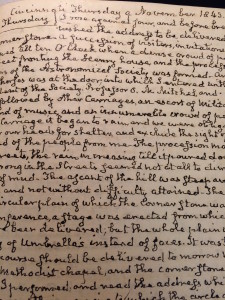

In Dayton and Columbus, more throngs came out to greet the Massachusetts Congressman and celebrated defender of the Amistad captives. It was a worthy but tiring tour, Adams thought. Yesterday–and yesterday was 8 November 1843–he gave another welcome address on the fly. The “Old Man Eloquent” felt exhausted, off his game. A raw winter’s cough had scuffed up his voice. But to Adams’s surprise, his “confused, incoherent and muddy” remarks only stirred “new shouts of welcome.” The next day, he climbed into a barouche and paraded, gingerly, through Cincinnati streets swollen by gusty “torrents.” His horses staggered and strained to ascend a nearby hilltop, site of the dedication ceremony for the new Cincinnati Observatory. From the center dais, Adams searched for eye contact and met a wall of umbrellas shielding his view. Now, his precious text bubbled and slid off the page, “so defaced by the rain, that it was scarcely legible.” Adams stood resolute, as the western downpour battered his last public address.

In a political career that spanned two continents and 51 diary volumes, President John Quincy Adams never quit easily, or gracefully. And he held back little from history. His diary opens new doors to the early American mind, and glories in its growing pains. Adams’s Cincinnati tale fires up some familiar motors of nineteenth-century thought: the communication/transportation revolution that broadened intellectual exchange; the political desire to suture western interests to the American union; and the rise of national scientific and cultural institutions. But there is a deeper story of antebellum selfhood and statehood here, and it’s (mostly) saved for us to read in the realms of his capacious diary.

John Quincy Adams, a less-loved leader of the fractious American republic, went west during a late and dramatic surge in his popularity. Crossing into Ohio, Adams was taken aback to learn that people liked him enough to attend his talks—and even to cheer. He inspired odes. He led city processions, and kissed at least one line of lady admirers. Baptist, Presbyterian, and Unitarian congregations turned out in small towns to worship with him. In the newspaper scrapbook that the family compiled of his western sojourn, John Quincy Adams’s crowds hailed the “child of the Revolution” as their patriarch. As one panegyric ran: “We come the FRIEND OF MAN to greet / The Hero who hath stood / Undaunted—scorning to retreat— / When slavery threatened blood.” A Christian soldier of Congress who tipped his words with flattery for the west’s “unparalleled growth and prosperity,” Adams savored his welcome/farewell tour. Scion of what was arguably the most famous family in America, the founder’s son finally seemed at ease in his birthright. When the rain blotted out his hard-won words, Adams winged it, and to wild applause.

Diary entries and press clips tell us something of Adams’s state of mind and self, but his encounters on the road likely say more about the moral landscapes that he saw. Given the 1841 Amistad decision’s notoriety, and his continued assault on overturning the gag rule in Congress, Adams became a familiar face to a nationful of strangers. In New York state, and again in Ohio, he attracted special notice for his antislavery stance. Early one morning at Columbus, David Jenkins visited Adams to “return the thanks of the coloured people of this city for my exertions in defence of their rights.” Jenkins had traded ideas and letters with the former president in spring 1841. Jenkins’s eloquence, then much in the same vein, clearly registered with the famed New Englander. “I hope and trust that the day is not far remote when Justice will be universally considered as the common right of all,” Adams replied to Jenkins, “unconfined by an unjust and oppressive distinction of colour or complexion…I am with respect, your friend & fellow Citizen.”

Tracking north, south, east, and west, the family archive captures flashes of American thought in motion. Often, when teaching history straight from the archive, I use John Quincy and the Adamses as cultural weather vanes, to decode the turns of American life from seventeenth century to present: feisty, expressive, glad to spin in new directions. Famous or infamous, who are your cultural weather vanes, and what makes you chase their “turn”? For, even in an archive as generous as these family papers, we must miss out on some moments (dinner table chatter, a few state secrets), as the best manuscript harvest cannot gather all. That talk at dawn, between John Quincy Adams and David Jenkins, is one more exchange to wonder at. It’s a few lines in a president’s diary, yes. But it points to the great growth of Adams’s mind, stretching from the plight of African captives to perceive the unfolding experience of African-American life in the west. Questions of race and justice threaded through every part of Adams’s latter life, and sealed his civic legacy. Adams’s meeting in Columbus stands as proof of the early American conscience hard at work—but not his words there, because we cannot have those words. Only David Jenkins can.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I’ve enjoyed every one of your posts Sarah. I loved this notion of Quincy Adams “winging” it, because he rarely comes off as the type to wing it. There’s also a tender humility in JQA’s surprise that people would cheer for him. It recalls for me one of my favorite moments in _The Education_, when a six-year-old Henry throws a tantrum at his mother because he doesn’t want to go to school. (Maybe this is one of your favorites?) His grandfather John Quincy (something like eighty at the time) emerges from study, puts on his hat, takes little Henry’s hand and walks him all the way to school, never letting go and never saying a single word. He just installs him in his seat once they get there and leaves. No lectures, just a quiet example. I looked up Henry’s great observation that immediately follows the account: “The point was that this act, contrary to the inalienable rights of boys, nullifying the social compact, ought to have made him dislike his grandfather for life. He could not recall that it had this effect even for a moment.” JQA seems to get a reputation for stiffness, but he comes off differently here and in _The Education_, not the least because there’s a certain affection in Henry Adams’ memories of his grandfather, his quirks and the like.

I’ve always loved the affectionate self-deprecation in that scene. It’s more or less forgivable and picaresque for being about childhood, especially when compared to the walloping stuff Henry throws out later: “Dillentantism” “The Abyss of Ignorance” and so on. Thanks for another great Adams post.

Peter, thanks so much, and I’ve greatly enjoyed your work, too. Looking forward to reading more!

For the procrastinators, the dissertators, the late-night laborers, and the conference-goers toiling at comments on the plane, I think that JQA would have shown great sympathy. From his Harvard days to his big Congressional finale, often he wrote into the wee hours of the morning to make a deadline. He was always on the road, and his family made him famous in a way that he could never shake. Perhaps his inner rebellion endeared him to me; he became less of a gloomy, crabby Yankee and more of a last-minute genius, a bright-burning intellect happy to prowl after new ideas in any terrain.

Oh, and that IS one of the warmer family sketches that rounds out Henry’s so-called “Education”–which I hope is still taught in American intellectual history classrooms everywhere. Henry idolized JQA and, far more importantly, his cosmopolitan grandmother Louisa Catherine. You’re right, of course, that Henry’s vignette tells us a great deal about how Victorian children viewed the antebellum patriarchy and its insistence on tradition. But perhaps his little brother Brooks, who was JQA’s prospective biographer at 20th century’s dawn, offers another revisionist view of his polarizing and prolific grandfather. In all of literature, Brooks found just one corollary for JQA: Moses.

I really liked the image in this passage: “the political desire to suture western interests to the American union.” I rarely think of the Founding generation and members of the early Republic as working *actively* to create more of a common culture—something beyond mere political or economic calculation, or that longer sense of what is later called “manifest destiny.” But I could imagine JQA, at least, as someone really desiring a true union. – TL