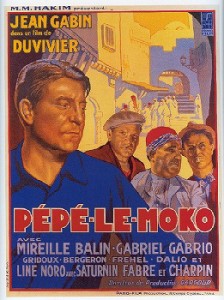

Last week in my film noir colloquium, we watched Pépé le Moko (1937), the French poetic realist masterpiece about a French jewel thief holed up in the Casbah in Algiers, longing for escape.[1] The film is largely about working class self-transformation. In the Casbah, Pépé (Jean Gabin) lives like a king, enjoying wealth generated by a big jewel heist that took place in Paris two years earlier, the adoration of the other denizens of the Casbah, and the protection of his surroundings. He and the police both understand that, so long as Pépé is in the Casbah, they cannot capture him. But if he leaves the Casbah, he will be immediately imprisoned. As a result of this situation, Pépé at the start of the film is feeling trapped by the Casbah. His longing for escape grows when he meets Gaby (Mireille Balin), a wealthy and attractive French tourist fascinated by the exotic Casbah. Though he first notices Gaby’s jewels, he soon falls for Gaby herself. It turns out that she is a kept woman, attached to the much older and deeply unattractive Champagne magnate, Maxime Kleep (Charles Granval). Like Pépé she comes from the Parisian working class. And, like Pépé she seems to have become trapped by her riches. They each represent for the other a kind of escape back to their Parisian working-class pasts. When Pépé tells Gaby that she smells like the Metro, both understand it as a romantic and nostalgic gesture. But it turns out that neither can escape back to their roots. At the end of the film, Gaby – having been misinformed by the police that Pépé has been killed – boards a ship back to France with Kleep. Pépé, unable to stop himself, leaves the Casbah to chase after her and is captured by the police as he boards the boat. As Gaby stares at the Casbah from the deck, dreaming of her failed hope for escape, Pépé manages to kill himself with a pocketknife, thus effecting the only escape that the world of the film offers him.

Last week in my film noir colloquium, we watched Pépé le Moko (1937), the French poetic realist masterpiece about a French jewel thief holed up in the Casbah in Algiers, longing for escape.[1] The film is largely about working class self-transformation. In the Casbah, Pépé (Jean Gabin) lives like a king, enjoying wealth generated by a big jewel heist that took place in Paris two years earlier, the adoration of the other denizens of the Casbah, and the protection of his surroundings. He and the police both understand that, so long as Pépé is in the Casbah, they cannot capture him. But if he leaves the Casbah, he will be immediately imprisoned. As a result of this situation, Pépé at the start of the film is feeling trapped by the Casbah. His longing for escape grows when he meets Gaby (Mireille Balin), a wealthy and attractive French tourist fascinated by the exotic Casbah. Though he first notices Gaby’s jewels, he soon falls for Gaby herself. It turns out that she is a kept woman, attached to the much older and deeply unattractive Champagne magnate, Maxime Kleep (Charles Granval). Like Pépé she comes from the Parisian working class. And, like Pépé she seems to have become trapped by her riches. They each represent for the other a kind of escape back to their Parisian working-class pasts. When Pépé tells Gaby that she smells like the Metro, both understand it as a romantic and nostalgic gesture. But it turns out that neither can escape back to their roots. At the end of the film, Gaby – having been misinformed by the police that Pépé has been killed – boards a ship back to France with Kleep. Pépé, unable to stop himself, leaves the Casbah to chase after her and is captured by the police as he boards the boat. As Gaby stares at the Casbah from the deck, dreaming of her failed hope for escape, Pépé manages to kill himself with a pocketknife, thus effecting the only escape that the world of the film offers him.

Pépé le Moko is about many things. But this time through, I especially noticed the theme of working-class self-reinvention, a subject that I had been thinking about because of the recent death of David Bowie.

If Bowie was known for anything, it was his great capacity for self-transformation. Not surprisingly, Bowie’s transformations – captured visually by this gif which started appearing all over social media after his death – were the topic of much of the commentary in the wake of his passing. And one of the most interesting threads of this commentary involved the discussion of an aspect of David Bowie’s biography – and persona – that I think most Americans rarely registered: his working-class origins. Mostly this commentary took place around the edges of the larger discussion. Brixton, the multiethnic working-class London neighborhood in which Bowie was born and spent his early childhood, held a memorial celebration for him. The English musician and activist Billy Bragg noted on Facebook how important art school was for Bowie (and Alan Rickman, another recently deceased artist from the English working class):

If Bowie was known for anything, it was his great capacity for self-transformation. Not surprisingly, Bowie’s transformations – captured visually by this gif which started appearing all over social media after his death – were the topic of much of the commentary in the wake of his passing. And one of the most interesting threads of this commentary involved the discussion of an aspect of David Bowie’s biography – and persona – that I think most Americans rarely registered: his working-class origins. Mostly this commentary took place around the edges of the larger discussion. Brixton, the multiethnic working-class London neighborhood in which Bowie was born and spent his early childhood, held a memorial celebration for him. The English musician and activist Billy Bragg noted on Facebook how important art school was for Bowie (and Alan Rickman, another recently deceased artist from the English working class):

Is it still possible for working class kids to realize their potential in such a way? The art schools are almost gone, those that survive now charge a fortune. The social mobility that Rickman and Bowie experienced is increasingly stifled.

Bowie’s changes were, of course, rather different from Pépé’s.

Pépé le Moko in its exotic location is very unusual among French poetic realist films, most of which take place in France itself. In focusing on working class self-transformation, it is also unusual. But it is typical of poetic realism in having working-class characters who are trapped by fate. Pépé and Gaby have successfully transformed themselves, but they find both themselves in situations in which there is no escape, except perhaps death. For a film about working-class characters who become rich through shady means but find themselves unhappy and missing their earlier, simpler lives, Pépé le Moko is oddly uncritical of riches themselves. Though they prove to be unsatisfying, riches are not exactly the cause of Pépé and Gaby’s unhappiness. Other characters in the film who are not rich also find themselves trapped by fate and longing for their past. For example, Tania (Fréhel), a former Parisian cabaret singer who is now the abused girlfriend of one of Pépé’s gang members in the Casbah, like Gaby and Pépé dreams of her youth in Paris. But she has been trapped by circumstances without affecting any class transformation. Working class self-transformation in Pépé le Moko is thus not so much tragic as it is ineffectual.

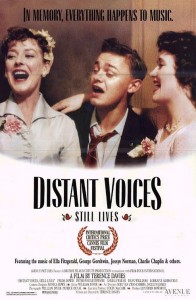

Bowie’s transformations, on the other hand, were triumphant. Resituating them in his working class, postwar English roots makes them all the more impressive. The filmmaker Terence Davies, a near contemporary of David Bowie’s, having been born just fourteen months before Bowie in November 1945, is a great chronicler of what it was like growing up queer and working class in post-war Britain. In the autobiographical Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), Davies presents the post-war, working-class, Catholic Liverpool world of his youth as repressive and patriarchal. Only popular movies and music seem to provide a kind of escape, though none of the characters in the film, which takes place just before the arrival of rock and roll in the 1950s, transcends the world it depicts.

Bowie’s transformations, on the other hand, were triumphant. Resituating them in his working class, postwar English roots makes them all the more impressive. The filmmaker Terence Davies, a near contemporary of David Bowie’s, having been born just fourteen months before Bowie in November 1945, is a great chronicler of what it was like growing up queer and working class in post-war Britain. In the autobiographical Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), Davies presents the post-war, working-class, Catholic Liverpool world of his youth as repressive and patriarchal. Only popular movies and music seem to provide a kind of escape, though none of the characters in the film, which takes place just before the arrival of rock and roll in the 1950s, transcends the world it depicts.

Bowie’s self-reinvention became a kind of beacon for other working-class youth. As the English philosopher Simon Critchley recently recalled:

The cool thing about Bowie is why working-class heterosexual boys like me found in Bowie a new landscape of possibility in relation to identity. We were dying our hair red and wearing mascara. And women were doing the same. What Bowie brought about was a kind of plasticity, or malleability, around questions of gender and gender identity. For him, there was something absurd about the standard heterosexual understanding of sexuality, and sexuality required a larger field of possibility and imagination. I think the liberating effects of that were felt by his fans.

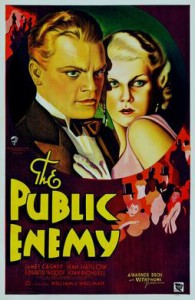

As I was thinking about Pépé and Bowie, I wondered what the American equivalents of them might be. Working-class identity seems less acknowledged or expressed in our popular culture. In both the 1930s and 1970s, Hollywood took a deep, if temporary, interest in the working class. The great cycle of “pre-Code” gangster movies of the early 1930s – The Public Enemy (1931), Little Caesar (1931), and Scarface (1932) – were absolutely chronicles of working-class self-transformation. Their protagonists were attractive, but tragic and ultimately undone by their ambition and ill-gotten gains. (Pépé le Moko, which is a kind of echo of these films, made half a decade and an ocean away, contains none of their moralizing about criminality in its equally tragic end.). My Man Godfrey (1936) and, in a roundabout way, Sullivan’s Travels (1942) present a more humorous view of class self-transformation. And the coming-home-from-war drama The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) has a subplot involving Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), a working-class kid who made officer in the war and now has to deal with returning to his pre-war status. In the 1970s, Hollywood’s working-class characters often seemed more stuck in place.

As I was thinking about Pépé and Bowie, I wondered what the American equivalents of them might be. Working-class identity seems less acknowledged or expressed in our popular culture. In both the 1930s and 1970s, Hollywood took a deep, if temporary, interest in the working class. The great cycle of “pre-Code” gangster movies of the early 1930s – The Public Enemy (1931), Little Caesar (1931), and Scarface (1932) – were absolutely chronicles of working-class self-transformation. Their protagonists were attractive, but tragic and ultimately undone by their ambition and ill-gotten gains. (Pépé le Moko, which is a kind of echo of these films, made half a decade and an ocean away, contains none of their moralizing about criminality in its equally tragic end.). My Man Godfrey (1936) and, in a roundabout way, Sullivan’s Travels (1942) present a more humorous view of class self-transformation. And the coming-home-from-war drama The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) has a subplot involving Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), a working-class kid who made officer in the war and now has to deal with returning to his pre-war status. In the 1970s, Hollywood’s working-class characters often seemed more stuck in place.

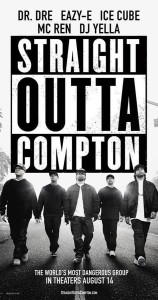

But then I suddenly realized that there was a much more contemporary drama of working-class self-transformation staring me in the face: Straight Outta Compton (2015). In many ways, Straight Outta Compton is a remarkably by-the-books musical biopic about the rise of N.W.A. and especially Dr. Dre. The scene in which Dre (Corey Hawkins) and Snoop (Keith Stanfield) spontaneously generate “Nuthin’ But a G Thang” is a classic example of the ridiculous way Hollywood has presented the song-writing process in films going back to the introduction of sound in the 1920s. Like many a biopic, the film is also a rags-to-riches story. And although race is a more obvious focus of the film, Straight Outta Compton is also very much about class.

But then I suddenly realized that there was a much more contemporary drama of working-class self-transformation staring me in the face: Straight Outta Compton (2015). In many ways, Straight Outta Compton is a remarkably by-the-books musical biopic about the rise of N.W.A. and especially Dr. Dre. The scene in which Dre (Corey Hawkins) and Snoop (Keith Stanfield) spontaneously generate “Nuthin’ But a G Thang” is a classic example of the ridiculous way Hollywood has presented the song-writing process in films going back to the introduction of sound in the 1920s. Like many a biopic, the film is also a rags-to-riches story. And although race is a more obvious focus of the film, Straight Outta Compton is also very much about class.

Dre and the other members of N.W.A. want to get out of the awful situations of their youth. But unlike Pépé or Bowie, their reinvention involves representing and marketing the world from which they hope to escape. Like a number of other strains of American popular music – including folk, country, and, often, rock – gangsta rap is built on a kind of working-class authenticity. But while musical authenticity can, at times, be banal or even conservative, in the right hands, its performance can suggest the often unexpressed possibilities of working-class life.

There’s a wonderful short video of Ice Cube celebrating the Eames House[2] in the middle of which Cube declares “before I did rap music, I studied architectural drafting.” It’s a fabulous and slightly jarring moment. If Bowie’s art school roots are clearly part of his persona of self-transformation, Cube’s roots in architecture seem seem to come out of the blue. And yet Cube is both very much himself and very much in character in this video, comparing the Eames’s architecture to sampling and declaring “this is going green 1949-style, bitch.” Instead of showing his own plasticity, as David Bowie always did, Ice Cube is showing the capaciousness of his authenticity-driven persona. Why transform yourself when you can sample? Cube contains multitudes.

[1] The film is indirectly responsible for an important piece of American popular culture. Pépé le Moko was remade in America as Algiers in 1938, with Charles Boyer as the romantic jewel thief. His performance as Pépé le Moko apparently inspired Chuck Jones to create the cartoon character, Pépé le Pew.

[2] Seriously. This is terrific. It’s only two minutes and fifteen seconds long. If you haven’t seen it yet, watch it now.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Ben: Thanks so much for this, and in particular the link to Ice Cube talking LA culture, architecture, and the Eames House. I love the black-and-white effect of the video.

On your post generally, is it about *representations* of working-class self-transformation, or the subject matter itself? Seems more of the latter, definitely by the end. – TL

Good question! I went back and forth on that title (I originally had “politics of” rather than “representations of”). I went with “representations” because: 1) PÉPÉ LE MOKO (and, for that matter, STRAIGHT OUTTA COMPTON) are clearly representations of it rather than than the thing itself and 2) though both Bowie and the members of N.W.A. went through actual processes of working class self-transformation, their careers were performances / representations of that transformation. Ice Cube’s video on the Eames House is a good example of this. (I also considered making this more explicit in the post, but ultimately chose not to….maybe I needed a better editor 😉 )

Now that I think of it, the word I should have gone with was “Performance.”

Hopefully my question didn’t sound critical; I was aiming for conversational.

BTW: Pépé le Moko sounds like a wonderful film. How did the students react to it?

Students like PÉPÉ LE MOKO (this is the fifth or sixth time I’ve taught it). It’s a lot of fun.

And no, I didn’t take your question as an unfriendly one…it just honestly raised an issue that I’d waffled on when titling the post 🙂