The following short guest post is by Mark Edwards.

The title of this post is a bit of a joke. Are the 1990s REALLY history yet? As a twenty-something during that era, I’d have to say no. But what about for my students? To them, the 1990s are like what the 1960s were for me in the 1980s. So, whether or not I (or we) “feel” like the 1990s are historical, they are; and we have to get busy making sense of them.

The title of this post is a bit of a joke. Are the 1990s REALLY history yet? As a twenty-something during that era, I’d have to say no. But what about for my students? To them, the 1990s are like what the 1960s were for me in the 1980s. So, whether or not I (or we) “feel” like the 1990s are historical, they are; and we have to get busy making sense of them.

This is an especially timely issue for me as I begin work on a historiographical essay for the 1991-2001 era. When first offered this assignment, I thought I had no clue where to begin. The recent AHA panel (and blog series here) on the culture wars then came to mind. I realized I might know more about this time than I had initially thought. In fact, writing on the 1990s would give me the chance to work out some unanswered questions I have about the culture wars.

First, a general observation: What is it about the 90s in U. S. history? The 1790s, the 1890s, the 1990s—they were each difficult decades characterized by profound ideological, moral, and social conflict. And, yet, out of each seemed to emerge a new consensus: Jefferson’s Empire of Liberty and Jackson’s Democracy; the Roosevelts’ Progressivism or New Deal Order. Was a similar dynamic at play in the 1990s? My preliminary answer would be Yes. Amidst the real fracture of the culture wars, neoliberalism was finding bipartisan support and institutional expression. Capitalism won with and without family values.

My question at this preliminary stage is: How would you narrate the 1990s? Is the “fracture+consensus” storyline I’m suggesting the best one to make sense of that era? Notice that I write “+” rather than “versus” or “within” because I’m not ready to commit to how those two themes might interrelate. I’m especially wondering if it is possible to take both the culture wars and neoliberalism seriously at the same time, or must we prioritize one over the other (as, for instance, Thomas Frank has been accused of doing)? Finally, and perhaps most importantly, what studies do you think should be highlighted in a historiography of the 1990s (Age of Fracture and A War for the Soul of America are already on the list)?

17 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

It seems to me that the most important “event(s)” marking the 1990s as the beginning of a new era, markedly different in feel and tone and fear and function from what came before, is the (seeming) end of the Cold War. So I guess I’d start the 1990s in 1989. And it seems to me that the most important cultural and economic developments in the 1990s would be “globalization” of corporations/trade and the rise of the internet/world wide web. I do think it’s possible to take cultural conflicts and neoliberalism seriously at the same time, but I’d argue that 1) neoliberalism is a movement *in* the culture wars, not outside of them and 2) neoliberalism seems to be the winning side.

I doubt that’s of any help, but thought I’d toss it out there.

It’s GREAT help, LD–thanks for it!!

It seems to me that the most important “event(s)” marking the 1990s as the beginning of a new era, markedly different in feel and tone and fear and function from what came before, is the (seeming) end of the Cold War.

I’d agree with L.D. on this (I might well omit the “seeming,” though I understand why she includes it).

To put the ’90s in context, even for someone mostly concerned w ‘domestic’ developments, I think there’s a good case for starting w/ fall of the Berlin Wall (as symbolic marker), dissolution of USSR and end of the Cold War (’89-’91, though the roots of these developments of course go back earlier). Also the Gulf War and Bush 41’s (somewhat premature) proclamation of a ‘new world order’ (plus Fukuyama on ‘end of history’). Then there are int’l developments in the mid-90s that have effects on U.S. politics etc. (And some that don’t have full effects until later: e.g. bin-Laden’s formal declaration of war vs the U.S., largely ignored at the time, is in ’96 or thereabouts.)

I suspect it’s maybe a little too early for a historiography of the ’90s, but on the end of the Cold War and related matters there’s a substantial literature by now. One recent addition is James G. Wilson, The Triumph of Improvisation: Gorbachev’s Adaptability, Reagan’s Engagement, and the End of the Cold War (2014). (Was the author’s dissertation. Not a leftish account in any sense. The four key figures in the bk are Gorbachev, Reagan, George Schultz, and Bush 41.)

Thanks Louis! One question going forward in this discussion is how much most Americans really paid attention to the end of the Cold War. My gut sense is that they were much more engaged with the culture wars than they were the collapse of the Soviet Union. In other words, I’d start the story with the domestic over the geopolitical.

Mark — The focus of most people’s attention in this period is a good question and you could well be right about that.

One of my favorite works that covers this period is:

Walter LaFeber, Michael Jordan and the New Global Capitalism, (New York: W. W. Norton, 2002).

I think it helps us look at pop culture (and the explosion of branding and MNCs), globalization/free trade/cultural imperialism(?), and the eventual war on terror in a certain way. At least, that’s how I try to make sense of it in my survey, with the caveat to my students that we’re often trying to interpret history on the fly.

Also, in my survey I look less at the “end” of the Cold War, and more at the question of possibilities in a new world order. You have the U.S. trying to figure out its role and place in the world (are we the policeman?) — we see this in Rwanda, Kosovo, Bosnia, and the Persian Gulf.

FWIW: The long decade perhaps goes from the fall of the Berlin Wall to 9/11, from the rise of the personal computer into 50 percent of households to the start of Google and the release of the iPod, the decade in which Walmart went nationwide. In my memory it wasn’t a difficult decade, it was a hopeful decade (for straight white males), something like I imagine the 1920’s to have been, with lots of froth (the tech boom). AIDS was the big cloud.

Bill, that’s how I periodize the era for teaching the survey: 1989 – 2001. Makes sense for all the reasons above.

Addenda: the Beloit college mindset list for 2016 college freshmen is always interesting.

https://www.beloit.edu/mindset/previouslists/2016/

The thing about the end of the Cold War is that not U.S. foreign policy changes radically in the era of ‘unipolarity’ (or what Krauthammer notoriously called ‘the unipolar moment’); it doesn’t. There are eventually some reductions of U.S. soldiers in Europe, but not a drastic reduction; NATO is expanded and turned into an instrument of (allegedly) humanitarian intervention in Kosovo. The Gulf War showcases the supposedly antiseptic character of high-tech ‘precision’ munitions, the effect of which some Americans eagerly consume on their TV screens (never mind e.g. the thousands of Iraqi soldiers killed when attempting to retreat or the subsequent devastating effect of sanctions on Iraqi civilians).

That said, does it make sense to suppose that the dissolution of the Cold War adversary, pivot of a conflict that had been the subject of so many political tracts and bad novels and movies (and an occasional decent one, I suppose) from the 1950s to the 1980s, had no effects on the American collective psyche and its expression in ‘culture,’ pop or otherwise? Probably not (i.e., no, it does not make sense to suppose that).

correction first sentence:

not that U.S. foreign policy etc

Thanks for this post, Mark. For what it’s worth (probably not a lot), I wrote about the 1990s in American religious history a while back I mostly used a culture wars framework; there are some good hip hop links in the post.

See here: http://usreligion.blogspot.com/2014/10/the-1990s-in-american-religious-history.html

Ah, yes, I remember this post now, Charlie–it’s wonderfully insightful and very helpful!! Glad to have it here with all the other excellent suggestions above.

Dr. Edwards, thanks for this post–quite the thought-provoking piece, as I am also starting to think about the 1990s in historical perspective (despite growing up during this decade).

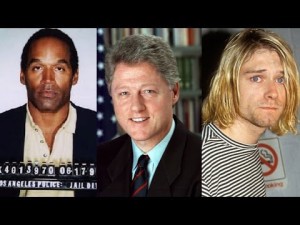

The final chapters of Julian Zelizer’s “Arsenal of Democracy” provide a good background for foreign policy in the 1990s. As Andrew, LD, and Louis have pointed out, it was an interesting era for American foreign relations. But turning to the domestic front, framing this question around issues of race changes things a bit–the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, the O.J. trial, the shooting of Amadou Diallo by the NYPD, and the 2001 Cincinnati Riots–coupled with debates about race, crime, and welfare centered around “The Bell Curve” and the welfare reform law, creates an interesting narrative one has to wrestle with. Just what *defined* race relations in the 1990s? And I didn’t even touch on debates about immigration and affirmative action. These questions touch on *both* neoliberalism (shown in Lester Spence’s new book, *Don’t Knock the Hustle*, which might be worth looking at for historiographic reasons) and the Culture Wars. In sum, the 1990s is definitely a decade worth studying–and I look forward to seeing what you produce next!

Great points, Robert! and thanks for the book recommendations as well. I’m tempted to think of neoliberalism in mainly economic and foreign policy terms (NAFTA, the China trade bill, ending Glass-Steagall). But you’re right that the term is relevant to domestic and race issues as well.

Thanks, Mark and all. Great post & thread! To toggle between pop culture, standard scholarly narratives, and the print culture of 1990s ideas, why not assign straight from the archive? With a nod to one of #USIH15’s themes, I note here the collections of several libraries that house that quintessential ’90s-era public(ish) forum for ideas and debate, namely, zines:

1. Barnard College Library: https://zines.barnard.edu

2. University of Iowa: http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/sc/resources/zineresources/

3. Duke University: http://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/findingdb/zines/

4. San Francisco Public Library: http://sfpl.org/index.php?pg=2000003501

5. For more U.S. collections, please see: http://www.lib.utexas.edu/subject/zines

This is quite the helpful thread when looking at the 90s, though I’d like to emphasize the role of technological growth during the period. In particular, the increasing importance of the internet and telecommunication. While not at the age of social networks, we do see the growing role of the internet to mediate social, cultural and economic interactions.