As many of our regular readers probably know, I used to be a participant in what members often refer to as “the atheist community.” I’m not going to go over the story of how I migrated out of that crowd – if you are curious I have written about this extensively elsewhere – but I did think to highlight one of the more interesting public intellectuals I came across due to my interest in ontological questions.

Unlike the infamous three-headed hydra of New Atheism – Dawkins, Harris and Hitchens – Bart D. Ehrman comes from a background of both deep religious belief and sustained academic study. Converting to evangelical Christianity as a teenager, Ehrman pursued his faith through education, graduating from Wheaton College and receiving his PhD and Masters of Divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary. Yet it was in graduate school that Ehrman first discovered the potential of scholarly analysis to modify his views on the origins and meanings of scripture, and years later he finally felt unable to maintain his faith.

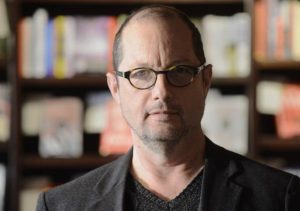

This seismic change in personal belief, however, did not alter Ehrman’s love for the study of early church history, and today he is the author or editor of two-dozen plus books and the James A. Gray Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. However, I became familiar with Ehrman the way most of his readers likely did – through the several books he has written for popular audiences exploring the complex and often self-contradictory Gospels, approaching problems such as the origins of the New Testament in books such as Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why and Jesus, Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (And Why We Don’t Know About Them.)

As a graduate student in history, I appreciated Ehrman as a refreshing example of how debates about religion and belief must be informed by an historical awareness and an approach that incorporates, rather than scorns, the analytical techniques of the humanities. I will not go as far as to say that most “active” atheists do not like history, but I think it is fair to argue that the majority of them do not really sufficiently understand or appreciate it. In concern to xenophobic and racist arguments about Islam this is, of course, particularly problematic, but the problem persists everywhere. Ehrman’s books provided me with a way of exploring the issues I was investigating in a language and style I found both familiar and more congenial than the abstract, ahistorical detachment of other non-faith based commentary. On the other hand, he also made his books accessible enough to count as pleasure reading; although I actually count early Jewish and early Christian history as one of my favorite historical subjects, I not surprisingly lacked the time to delve into the professional scholarship and all the minutia that accompanies it. Ehrman, however, writes both thoughtfully and engagingly.

Ehrman is also a rare bird within the atheist community: a well-known and liked public intellectual who scorns the term “atheist” and insists that the more proper way to describe his theological position is “agnostic.” (The only other example of this that comes to mind is Neil DeGrasse Tyson, who, much like Bill Nye the Science Guy, has the redeeming quality of actually caring more about making people excited about science than shitting on religious belief.) Moreover, while he often debates evangelists and scholars to his right who maintain that the scriptures are more historically reliable than his books suggest, he also has spent considerable energy battling a fringe group of atheists who are hell-bent on insisting that, contrary to scholarly consensus, no man (human or otherwise) named Jesus ever lived in the ancient Middle East preaching about the Jewish God.

Of course not all scholars are sanguine about Ehrman’s work, and some have accused him of oversimplifying the historical consensus. My guess – not being an expert – is that this has to be true, to some extent, in order for Ehrman to write the kind of books that he does, lest they turn into chronicles of every moderately significant historiographical debate. Even so, I refuse to subscribe to the idea, floated by David Hollinger a few years ago at the S-USIH conference, that to write accessible books is to degrade the art and craft of history. This is especially the case with Ehrman who, by walking his readers through the methods of historical investigation, lays his analytical tools on the table and produces books that not only expose readers to early Christian history, but also provide them with a tutorial on how historians go about the process of writing history.

But more than anything else I appreciate Ehrman’s bravery. By this I do not allude to his willingness to take on the ire of both puritan atheists and Christians – although I imagine that can be exceptionally exhausting – but rather his willingness to show how his internal life and his scholarship have intersected. His favorite book of mine (although I have yet to read his latest, How Jesus Became God) concerns the question of evil and suffering and how it was ultimately the failure of scriptures to provide him with what he regarded as acceptable or convincing answers to that question that led him to concluding he could no longer consider himself a Christian. In an academic culture that actively discourages recognizing, or at least encouraging, the unavoidable intersection between our selves and our work, I find such an approach profoundly invigorating – because after all, that’s the deepest reason I care about history in the first place.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this interesting post.

Do you classify Ehrman as a “public intellectual” because of the subject matter he investigates (history and religion), which might necessarily imply a “public” for some people, or due to his attempt to reach a “popular audience”? Does he frequently appear on radio/tv?

Do you know if the evolution debates were a factor in his development as a person? Some scholars find that the turn to “higher criticism” was more damaging to Christianity (in the long run) than Darwinism. Does he take this position?

Mark

Hi Mark —

On the first question, it is because of the latter; not only does he try to engage with a larger audience, but he is willing to actually tackle some “fundamental questions” and discuss them from a personal perspective, rather than just allude to them as though they constitute impersonal forces he has no take on. I really appreciate that and think that honesty elevates him from just maybe a widely read historian to a public intellectual.

He is not often on TV, but there are lots of videos of talks and lectures he has given on YouTube.

And no, he does not engage with the evolution debate. The stuff he focuses on is really much more focused; i.e., what we do and do not know (or cannot claim to know) about early Christian history.

I encountered Ehrman when I listened to his course on the Historical Jesus. It was free when I found it but now seems to only be available through Great Courses.

http://www.thegreatcourses.com/courses/historical-jesus.html