In 1963, the young historian Walter Nugent plunged into what was already a roiling debate about the putative xenophobia of the Populists of the late nineteenth century. His book, The Tolerant Populists: Kansas Populism and Nativism, opened the first chapter by asking the reader to recall the Raphael painting Saint George and the Dragon, which has been on display in the National Gallery of Art since the 1930s.[1]

In 1963, the young historian Walter Nugent plunged into what was already a roiling debate about the putative xenophobia of the Populists of the late nineteenth century. His book, The Tolerant Populists: Kansas Populism and Nativism, opened the first chapter by asking the reader to recall the Raphael painting Saint George and the Dragon, which has been on display in the National Gallery of Art since the 1930s.[1]

One of its [the painting’s] happiest qualities is its utter lack of ambiguity: good and evil are unmistakable; moral judgment is simple. For almost half a century, the Populist was one of the St. Georges of American historical writing. Yet suddenly in the 1950s it appeared that he was not that at all but in fact a dragon and a fierce one. The awful truth emerged that in fixing good and evil upon their canvases, historians had got the combatants reversed.

Nugent’s book was a spirited rebuttal of this new demonology, in which the Populists of the 1890s became the grandfathers of the McCarthyites of the 1950s—paranoid, nativist, anti-intellectual, and deeply hostile to change. Nugent didn’t stop there, however: he also sought to demonstrate the immense benevolence and virtuousness of the People’s Party: the Populists were St. George after all.

This fifty-plus year-old historiographic quarrel may have been on your mind as well recently—Yoni Appelbaum had a tweetstorm along these lines last month which concluded with “Five years from now, we’ll reap a bumper crop of dissertations on the Populist Party, informed by this election. Can’t wait to read them.”

But what Appelbaum, I think, sees as linking Populism to Trumpism is not so much the internal dynamics of the two movements (“Populism isn’t the same as Trumpism. But there are echoes,” he writes) but rather the similar difficulties that one faces in trying to characterize them, to plumb their motives—or even to decide whether it’s worth trying to plumb their motives. Looking ahead to the interpretive challenges which future historians will face, Appelbaum writes, “It’s easier, at a century’s remove, to pick out policy proposals that seem prescient or attractive, deemphasizing hateful rhetoric. / Conversely, it’s easy to dismiss the ‘paranoid style’ of people who’re long dead, overlooking the real concerns that animate it.” Perhaps 2083 will see a slim monograph titled The Tolerant Trumpists.

Nugent, I think, was wrong in using Saint George and the Dragon as a metaphor for the historiographic quarrel about the Populists. While it nicely captures the monochromatic nature of the debate, the chivalric narrative is the incorrect frame. The issue at the heart of any disagreement over a populist group or movement—whether we’re talking about the People’s Party or Trump’s followers—is not whether we should recognize them as heroes or not but whether we should recognize them as victims. What was so profoundly shattering about the historiographical upheaval caused by Richard Hofstadter’s charge that the Populists were anti-Semites was not that it made them less valiant in their political quest but that it placed them outside the reach of empathy. That is why “Tolerant” is in Nugent’s title: what had to be restored was not the validity of the Populists’ political program or the accuracy of their diagnosis of what was wrong with the new corporate order but their membership in the community of basically decent people. It is why, I think, J. D. Vance is so concerned early on in Hillbilly Elegy (which I’ve been reading a few pages at a time over the past week) to reassure us,

Nearly every person you will read about [in this book] is deeply flawed. Some have tried to murder other people, and a few were successful. Some have abused their children, physically or emotionally. Many abused (and still abuse) drugs. But I love these people, even those to whom I avoid speaking for my own sanity. And if I leave you with the impression that there are bad people in my life, then I am sorry, both to you and to the people so portrayed. For there are no villains in this story. There’s just a ragtag band of hillbillies struggling to find their way—both for their sake and, by the grace of God, for mine.

When I first read over this passage, I nearly skipped over it as an almost routine act of empathetic exculpation: something more like a shrug of humility, or at best a “cast the first stone” acknowledgment of human frailty. But its quasi-banality actually masks a more dispositive certainty. Vance is not saying that he (or we) cannot judge because we are all “deeply flawed.” He is instead saying that judgment has already been rendered and it is in their favor: they are acquitted, not simply released because of a hung jury.

The line between empathy and exoneration is a fine one, and it accounts, I think, for some of the gritted teeth and stony frustration that one can feel in reading any of the exchanges in a current debate—mostly among liberals and leftists—over the way “economic anxiety” has become both a keyword for a class-first strategy of envisioned outreach to the white working class from the left and a sort of punchline for journalists pointing out the virulent racism and anti-Semitism that goes on at Trump rallies and in digital spaces like Twitter. There seems to be very real differences in the way one might parse the data that has been collected so far about Trump supporters—differences enough to support either one of two starkly opposed viewpoints: yes, the “economic anxiety” among Trump supporters (or a big enough swath of them) is real and it should be addressed by the left and/or by Democrats; no, “economic anxiety” is a screen for an open sewer of racism, misogyny, and xenophobia which no progressive should go anywhere near.

This debate over “economic anxiety” appears to be a question of political tactics: is there a chance for a coalition rooted in class? But just as the historiographical debate about Populism smeared together the acts of empathy and exoneration (“they suffered… they were good people”) so, I believe, those who—like Jamelle Bouie or Matt Yglesias—simply reject any outreach to Trump’s supporters because they intuit a future redemption of the Trump movement as less morally noxious than they believe it is. In order to maintain a focus on the racial and gendered elements of the Trump movement, Yglesias et al. have to hold the line on class: even if, they are saying, there is validity to the economic anxiety argument, that argument is not worth making. Something can be both true and yet a distraction from a larger truth, and this is a larger truth. Empathy is a bed too soft to lie in, they feel: the danger is that you won’t get up.

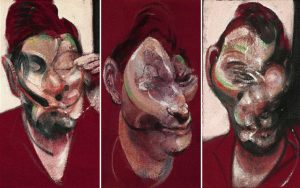

Populism is not best represented, I believe, by a classically straightforward painting like Raphael’s Saint George. It is better illustrated, rather, in the mode of Francis Bacon, whose figures confront us with a discomfiting ambiguity: are the contortions, the howls, the effects of agony or anger? Do we empathize or recoil?

Study for a Portrait 1952 Francis Bacon 1909-1992 Bequeathed by Simon Sainsbury 2006, accessioned 2008 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T12616

Which will it be, then: pity or terror?

Some of the contributions to the “economic anxiety” debate:

Matthew Yglesias, “Why I don’t think it makes sense to attribute Trump’s support to economic anxiety,” Vox, 8/15/2016

Brian Beutler, “I Started the ‘Economic Anxiety’ Joke about Trump—and It’s Gone Too Far Now,” The New Republic, 8/16/2016

Derek Thompson, “Donald Trump and ‘Economic Anxiety,’” The Atlantic, 8/18/2016

Jamelle Bouie, “Do Half of Trump’s Supporters Really Belong in a ‘Basket of Deplorables?’” Slate, 9/11/2016

Dylan Matthews, “Taking Trump voters’ concerns seriously means listening to what they’re actually saying,” Vox, 10/15/2016

E. J. Dionne, “Even if Trump loses big, the anger will remain,” Washington Post

James Kwak, “Economic Anxiety and the Limits of Data Journalism,” The Baseline Scenario, 10/17/2016

Mike Konczal, “Would Progressive Economics Win over Trump’s White Working Class Voters?” Medium, 10/18/2016 (in my opinion, the best article about this topic)

Seth Ackerman, “Sympathy for the Devil,” Jacobin, 10/20/2016

Connor Kilpatrick, “Fool Me Once,” Jacobin, 10/27/2016

[1] This painting was one of those bought by Andrew Mellon from the Soviet Union’s 1931 sell-off of part of the Hermitage’s collection. Along with about twenty other paintings, Mellon donated the Raphael as part of the inaugural set for the new National Gallery of Art.

17 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Andy, excellent — no, fantastic — post.

In many ways the “economically anxious” v. “racist/nativist” debate depend on a heuristic division between those two options that is not necessary for either (or both) of them to be persuasive.

This piece by sociologist Philip N. Cohen challenges the sharp binarism of the debate, along lines similar to what you’ve done above with your proposal of an alternate interpretive frame (or, an alternate canvas): Don’t Think Economic Anxiety Is Rational and Racial Anxiety Is Not

So on point, like always. It is telling how these political narratives are framed typically in either/or fashion, almost as if there was a phobia of multicausallity, hetoregeneity, or plain old complexity. From my perspective, the most empathetic position is grasping not only the economic anxiety and racial / nativist ideologies that Trumpists navigate and how these values vary depending on factors such as region and socioeconomic difference (working class versus struggling low-middle class, Appalachia versus suburbia, etc.), but also comprehending that even both elements do not explain fully the problem at hand. I think bringing up empathy as a political affect is a wonderful point, understanding that it is not the same as sympathy. To empathize is about imagining other worlds of being, glimpsing the affects, ideologies, and material circumstances that shape the experiences of others. And their own agency in said experiences: this is where the question of exoneration comes into play (or to be more precise, it doesn’t). At the same time, part of the process of empathy is understanding its epistemological limits, that we cannot altogether grasp the singularity of others, that we will never be able to decode their behaviors and thoughts completely.

Andy,

I haven’t kept up with the articles on this debate, some of which you list at at the end of this post; but I’m aware, from a bit of time likely ill-spent in the blogosphere (this blog excepted, of course) that one other article that has been cited is:

Zack Beauchamp, “White Riot,” Vox, 9.19.16

(it’s very long).

And a commenter elsewhere mentioned:

H. Farrell, “How C. Hayes’s ‘Twilight of the Elites’ explains Trump’s appeal,” Vox, 10.13.16

Haven’t read either one, or the P. Cohen piece L.D. links.

As both you and L.D. in her comment suggest, it should be possible to recognize that both elements are involved, in differing degrees depending on individuals. Mentioning economic anxiety does not “distract from” the recognition or, in some cases, centrality of xenophobia and racism, unless the debate becomes pointlessly nasty and either/or-ish, as it does in some online quarters.

[The Deaton/Case paper on mortality rates, although it’s probably gotten some overly broad interpretations by people who couldn’t be bothered to read it carefully, also should be mentioned here.]

p.s. I posted the above before seeing Kahlil’s comment, with which I agree.

So much agreement here. 😉

Thanks! All inspired by Andy’s masterful post.

Thank you all for these great comments, and for the links to other studies/essays. I especially love the deeper definition of empathy that Kahlil gives, and the many challenges that it entails.

One way of reframing what I was trying to get at above is to say that the concept of empathy is associated with a fairly narrow range of spatial metaphors that emphasize intimacy and alignment: we “walk a mile in someone else’s shoes,” as Harper Lee has it, or “see the world through their eyes.” Empathy is presumed to be disalienation; one can’t empathize with someone strange, for as soon as one initiates the act of empathizing, it is no longer strange.

I’m not convinced that’s a very helpful way of defining the limits of empathy, and I have been thinking about the ways that empathy can occur even when intimacy/identification/disalienation does not. Can I empathize with and yet remain estranged from someone? Maintain my distance and yet reach a genuine, connected comprehension of their worldview’s inner logic? I’m not sure; I feel like that would be a very different definition of empathy from what we are used to.

Another great, perceptive post. I’ve been thinking some lately about love and politics, whether “politics can be an expression of love” to quote from Invisible Man. It might not be empathy but there is agape love. I don’t have to agree with nor even like the other person, but can recognize their worth as a human being. For MLK of course this meant being made in God’s image. It had to have metaphysical backing in his case. You don’t write the other in your midst off this way. You can try to appeal to conscience, but that may not work. In that way you might try to understand them insofar as you encounter them as political opponents. Nothing scintillating there, but a thought. I wonder how that works with the more complex way you’re thinking about empathy.

I should direct blog readers to Bob Hutton’s sharp disagreement with the Vance book.

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/10/hillbilly-elegy-review-jd-vance-national-review-white-working-class-appalachia/

Hi Andy – found this piece in my mentions – nice, thanks. I think it’s important to sort out the response to race versus class privilege in this debate, which is what I was trying to get at in my post, where race anxiety is considered toxic and class anxiety is considered sympathetic, with the phrase: “privileges they protect may need to be forcefully degraded rather than just reasoned away.”

Got my own URL wrong: https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/

Hi Philip!

Thanks so much for clarifying. I actually owe knowledge of your blog (and the trackback that you saw) to L.D.’s comment above–she’s the one who made the connection to your great post.

Andy –

Part of the disagreement here has to do with how conceptual categories are used in historical analysis. I certainly don’t have a fix, but I’m glad you’re continuing along the lines of the earlier piece on “Historicizing, Fast and Slow: Trump, Precedents, and Novelty,” USIH 8.1.16. You’re probably right that historians’ standing depends largely on their ability to make convincing connections between past and present.

I like to think of this in terms of analogy, rather than precedent [Grant Lamond’s article on “Precedent and Analogy in Legal Reasoning” is worth a look], and it seems there’s a significant difference between tight narrative continuity and the sense of coherence that can emerge from a network of comparable cases scattered over temporal space, linked by analogous analytical terms and distinctions, even when no one is paradigmatic, and far short of a general theory.

With some reminding on your part, “Tolerant Trumpians” not only recalls Nugent, Hofstadter and the mid-century debates about populism, but the analytic categories in play at that time, which are then analogized to those in contemporary debates around “economic anxiety.” [It might be interesting to map these metonymic instances historiographically, as concerns about McCarthyism and the “radical right” were part of the background in Hofstadter’s time, as Trumpism is today.]

As we know, these terms and concepts often take the form of binary pairs analogized to each another as they are used to interpret historical instances, which then become themselves analogous, and perhaps produce a story in the end. Thus we build our sensible worlds. Some of these partially isomorphic distinctions include: class vs. status, rational vs. irrational or emotional, interest vs. expression or identity, material vs. ideal, class vs. culture, interests vs passions, interest groups vs identity groups, distribution vs. recognition; old social movements vs. new social movements, instrumental vs. expressive, gesellschaft vs. gemeinschaft, economic anxiety vs. racism, etc. [Philip Cohen nicely tries to scramble some of these.]

Relatedly, discussions often develop around how material being studied should be treated, sometimes leading to re-framings. Eg, think race as ethnicity or ethnicity as race, minorities as identity groups, blacks as Jews, women as a minority, or slavery as the black holocaust. This doesn’t even approach the intricacies of multiple intersecting categories. [For me, suggestive articles include Daniel Immerwahr, “Caste or Colony? Indianizing Race in the Un St,” 2007; Deepa S. Reddy, “The Ethnicity of Caste,” 2005; and Howard Brick, “Society,” 1997, on divisions in postwar social sciences around the salience of interests vs meanings, economics vs. culture.]

Andy: Love this. Thanks for taking the time to write up your thoughts on all of this.

Your passage on Vance, and the limits of tolerance and empathy generally, as well as the subject of ambiguity, have me thinking about the axis we variously call common/uncommon, normal/abnormal, or ordinary/extraordinary.

Is there, for instance, a “normal” in relation to economic anxiety? Is there a “common” level of tolerance? When does ambiguity, if ever, move beyond the ordinary? What empathy is ordinary and what is extraordinary?

When does ordinary pity become an exercise of extraordinary behavior, and hence a problem of terror?

When do normal emotions expand to overshadow everyone’s innate ability to participate in the realm of reason, or necessary empathy?

I don’t have answers to these questions. Rather, I wonder how to theorize along these axes in terms of populist politics. -TL

This interview w/ Arlie Hochschild is relevant:

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/red-states-depend-distrust-government/

Based on a 3-second search, I see she’s been publishing articles recently summarizing her book Strangers in their Own Land, which the interview is about. Weakest part of the interview seems to me to be at the end, where is she is optimistic that the “divides” can be bridged. ymmv.

correction: should read:

“where she is optimistic”

Last point on Hochschild: I want to make clear that all I’ve seen is this brief interview; haven’t read the book and thus am not necessarily endorsing what she writes there.

A commenter at the LGM blog criticizes Hochschild for (allegedly, at any rate) avoiding the issue of race — but again the reference seems to be to an interview, not the book:

http://www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com/2016/11/empathy-for-the-devil-i-i-mean-super-nice-misunderstood-salt-of-the-earth-types#comment-2315039

Andy, thanks so much for writing this. I have some thoughts about these calls for empathy, but decided not to post them here, for reasons. They’re up at my own blog for the moment, though I’m not sure I’ll leave ’em there. The damage from this election is going to last long after the election is over — but for pity’s sake I just want the damn thing to be over.

Bless Their Hearts