This past week we covered (“covered”) the War of 1812 in my U.S. history survey sections. I told my students right off the bat that I will not be asking them to recall the names of naval officers or the details of particular troop movements on the exam — though it doesn’t get much more memorable than “Oliver Hazard Perry,” or much more of a close call than the British burning Washington and marching toward Baltimore, or much more unambiguously lopsided than the Battle of New Orleans. Instead, I focused on some significant consequences of the war in terms of America’s place in the world (including its relationship to the native peoples in its midst and to its west) and in terms of the nation’s internal affairs and politics.

While I too don’t put much stock in historical precedents (history is not a lab science, or even a science; you cannot control variables that would yield comparable results at two different moments in time; our discipline is ideographic, not nomothetic, damn it!), in our narrative construction of the past, we can return (or, perhaps, often can’t help returning) to some recurring themes – not precedents or even prototypes so much as topoi. Implicit topoi underlie our attempts at historical analogies – that goes for professional historians, I think, but also for the public at large.

In thinking of the consequences of the War of 1812, one particular outcome seems possibly relevant to our current political moment (we will only know what is or is not relevant in retrospect): the end of the First Party system and, more particularly, the accidental and spectacular self-immolation of the Federalists as a viable national party. The underlying topos here might be something like, “when political parties bet it all on one outcome and lose big.”

In thinking of the consequences of the War of 1812, one particular outcome seems possibly relevant to our current political moment (we will only know what is or is not relevant in retrospect): the end of the First Party system and, more particularly, the accidental and spectacular self-immolation of the Federalists as a viable national party. The underlying topos here might be something like, “when political parties bet it all on one outcome and lose big.”

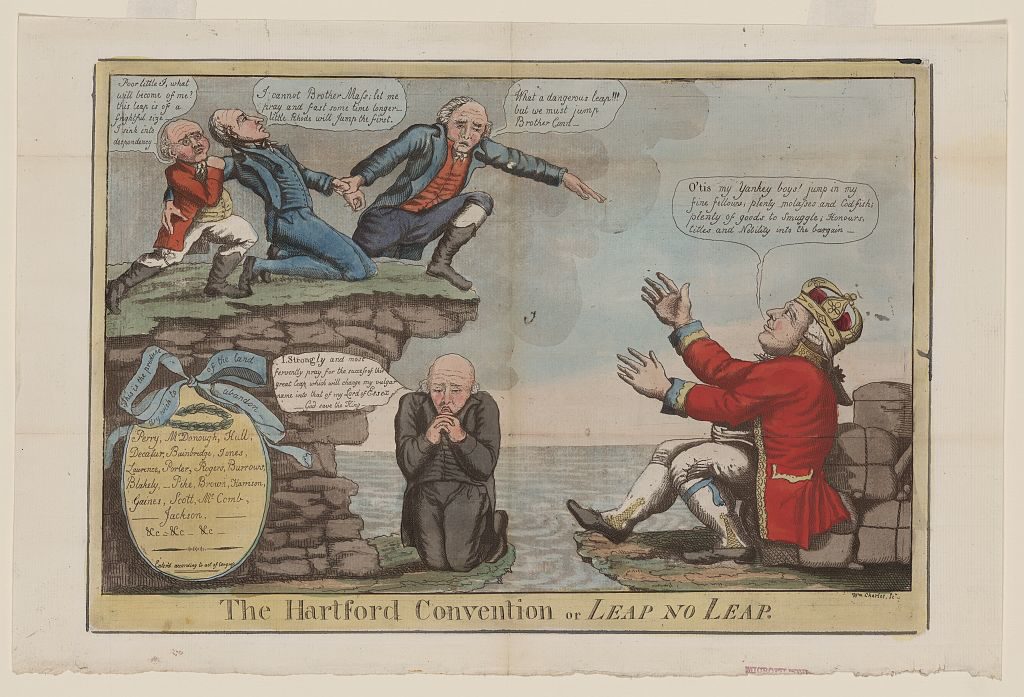

While Federalist opposition to a war that the United States ended up winning by simply not losing might have doomed that party anyhow, the nail in the coffin of the Federalists’ national political sway was the Hartford Convention, where New England leaders of that political party, sure that the stupid war was going to end in spectacular failure, openly discussed (though did not ultimately approve) the possibility of seceding from the rest of the country and making a separate peace with the British. Off the Convention’s envoys went to Washington to recommend a mixed grill of constitutional amendments that might fix everything wrong about the country, just in time to hear the welcome news of the Treaty of Ghent and the stirring news of the Battle of New Orleans.

Talk about terrible timing – terrible timing that was quickly taken as a sign of terrible (if not treasonous) judgment. So long, Federalist presidential aspirations. (But, as we know, hello – eventually – to the American Whigs.)

To be clear, I’m not saying that the closest or best historical analogy to our current political situation dates from the War of 1812. The “topos” of this election will emerge only in retrospect. Really, it was just what I happened to be teaching this week, and the Hartford Convention struck me as neatly emblematic of “betting so big and betting so wrong that you’re out of the game for decades.”

I think what we’re seeing at present seems to fit more neatly into the theme of “Mugwumps on steroids,” with many members of the Republican establishment (and not a few Republican-leaning newspapers) openly endorsing the Democratic candidate for president. This was not the end of the Republican party, but it was the end of a few Republicans’ careers within the party. Teddy Roosevelt, on the other hand, stuck with the party’s nominee, proving himself to be a loyal Republican. In retrospect, he made the right bet — not for that election, but for his own future, and for the future of his party. But when he laid his bets again in 1912, strong as a Bull Moose, he made a losing bet, as did the progressive Republicans who rallied to him – losing not only that election but also forfeiting any possibility for a progressive movement within the Republican party.

It seems to me that Republican leaders today who are trying to figure out how to triangulate around their party’s nominee, if they’re thinking about historical precedents or analogies or recurring themes at all, are probably most mindful of the example of Teddy Roosevelt. The moral of the story as they are reading it or telling it to themselves seems to be this: stick with the party and the party’s nominee, for your own sake and for the sake of the political principles you hope to put into practice.

We’ll see what happens, and we’ll figure out later how to frame the narrative as part of a longer history – well, somebody will figure that out. It’s hard to frame the narrative of the soon-to-be historical moment that you are currently living in, even if framing historical narratives is what you do for a living.

But as we are rummaging through the historical lumberyard looking for some handy materials to construct even a makeshift narrative of the present, a plank or two from the end of the First Party system strikes me as something that might prove useful in building the frame for one part of the story. But historical use is not the same as historical precedent. If the story we tell ends up echoing themes from the demise of the Federalist party, it does not at all follow that some Era of Good Feelings, in name or in fact, awaits us around the corner.

12 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I have a word besides Mugwump for you.

Try “mudsill.”

http://socraticgadfly.blogspot.com/2016/10/mudsill-one-word-that-explains-trump.html

Thanks — though I’m not looking for an explanation of Trump and Trumpism here. On the “mudsill” as both a class and a cultural identity, Nancy Isenberg does a fine job discussing this history in her recently published White Trash. That was my summer beach read, and it was pretty good.

I just got the book and am on about page 50.

Nicely turned post. The last time I took a U.S. history survey was AP U.S. history in 12th grade — it was a pretty good course, but in my case a long time ago. Thus I had to spend a few seconds with the search engine reminding myself who the Mugwumps were.[*] Which, to be clear, is not a criticism of the post, but rather a self-criticism, since it’s probably something I should have remembered.

——

*For the heck of it, I also wondered if I had a very quick way to look up ‘Mugwump’ that did not involve the computer, and so just now I pulled from my shelf my one-volume 1983 edition of The Concise Columbia Encyclopedia — in some ways a quirky and far from altogether satisfactory reference work, but it happens to be the one general encyclopedia I have (and I have no encyclopedia of American history on the shelf since, unlike probably the majority of readers of this blog, I have no pressing, imperative reason to own such a work). To my pleasant surprise, the Concise Columbia does have a one-sentence entry for ‘mugwump’.

Thanks Louis. I wrote this post in a hurry, and realize that I didn’t manage the handoff very well between the current situation (“Mugwumps on steroids”) and the historical antecedent (the election of 1884, when a lot of elite Republicans backed

Chester ArthurCleveland).On today’s Mugwumpism…I don’t think any Republicans who have endorsed Clinton have a future in the Republican party, and I’m sure they knew that already. (Some might argue that they had no future even before they endorsed Clinton, or that they were has-beens anyhow, so their defections are no loss to the party.) On the other hand, the short list of establishment (non Tea-Party-type) Republicans who are not in the awkward position now of considering whether to “unendorse” Trump, having been pretty clearly against him from the beginning, could conceivably be the “rump” of a new party, maybe even a renewed Republican party, if the Tea Party, the Trumpists, and the Religious Right (not identical but overlapping) all scatter. But this is all speculation, and anything could happen between now and November, and/or after November.

It seems pretty clear, though, that the modern Republican party’s always-strained conservative coalition (in which, lately, the John Bircher-types who were allegedly driven out, or at least to the fringes, by movement conservatives, are now “the base” in so many senses of the word) is on the ropes.

Will the first-we-endorsed-him-then-we-unendorsed-him Republicans be pigeonholed by their political foes like the post-Hartford Federalists were, as politicians who put party before country when the country was in peril? Hard to say. But the anti-R ads for the next midterm elections almost write themselves.

If time lasts and we don’t die, as my granddad used to say, it should be an interesting few years.

But the way things are going lately, that seems like a really big “if.”

Gah. Not Chester Arthur. Grover Cleveland. Long day.

It’s always interesting to note the plethora of *former* elected officials vs. the paucity of *current* elected officials who do such cross-party endorsements.

Agreed that there’s a direct line in the GOP. Other than Trump having less connection to the religious right, his voters are the Buchananites of the 1990s.

L.D.,

I agree (and I think most everyone would agree) that Trump and this campaign have created new strains and potential or actual fractures within the Republican electoral coalition; and as you suggest the most interesting, though I suspect unlikely, outcome would be the creation of a new ‘rump’ party that managed to become more than a minor party. That indeed would amount to the emergence of a new ‘party system’ and that of course that hasn’t happened v. often in U.S. history (which, needless to say, doesn’t mean it’s impossible).

Assuming however the Republican party does not formally split but manages to stay at least quasi-intact, one group of Repubs who endorsed Clinton who might have some future in the Repub party as advisors (not candidates) are neocons like Robert Kagan, who can argue they went with Clinton solely on foreign-policy grounds (which, in Kagan et al.’s case, is an accurate statement). Whether a politician like Kasich has any future in the Repub party, regardless of the election outcome, seems more questionable.

(sorry, pls. ignore the extra “that” in last sentence of first paragraph)

Couldn’t remember who abandoned Goldwater in 1964 so found this piece http://www.rothenberggonzales.com/news/article/comparing-the-gop-divides-1964-and-2016 (dates back to May of this year).

It appears people like Cruz followed the rule implicit in 1964–give lip service to the nominee and preserve your future in the party. But will people who supported Trump post convention and pre-Oct 7 be hurt if they withrew their endorsement after Oct 7?

Surely there are counter-examples of presidential aspirants or other major political figures who, under similar circumstances, stayed loyal to the party and saw their political fortunes destroyed in the subsequent electoral disaster–for example, after the demise of the Whigs, or northern Democrats after 1860, or Republican loyalists after 1932, or HW Bush loyalists after 1992.

Well, it seems that the party is not over. But it has taken an ugly turn.

I teach three sections of U.S. history today. My job is to show up and offer what light I can for all my students — my immigrant students, my queer students, my students who proudly or quietly voted for Trump, my students who proudly or quietly voted for Clinton.

That’s why they pay adjuncts the big bucks, right?