“There was no system for managing so sinister a mess.”[i]

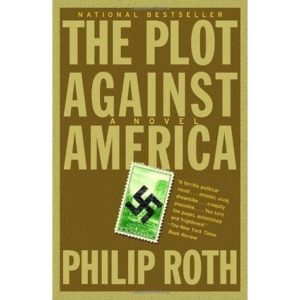

My post today follows up on my previous one from November 28th. Recalling that post, The Plot Against America is a fiction in the form of an alternate history. In it, the novelist Philip Roth considers what would have happened had Charles Lindbergh, buoyed by the America First movement, won the presidency over FDR in 1940. The novel is the story of the turmoil experienced by a Jewish American family in Newark, New Jersey as creeping fascism sets in over several months from 1941 to 1942. Roughly, the mood in the family’s enclave in Newark moves from shock to anger, defiance, then crippling fear, until something very near to chaos ensues.

The narrator of the novel is Philip Roth, who recalls from the remove of adulthood what happened in those months when he was between the ages of eight and nine as the events unfold. He reconstructs his boyhood thinking, reflecting on it and the reactions of his parents and members of his extended family.

The Roth family is divided over the Lindberg administration. Herman, the father, for most of the story is defiant in the face of Lindbergh’s administration, trusting that American history and its institutions will ultimately prevail. Bess, the mother, is most concerned for the safety of her family, and so worries about Herman’s principled obstreperousness and eventually lobbies for a move to Canada. Sandy, the eldest of the boys, for some time embraces the Lindbergh administration and its programs, only to rejoin the family fold much later in the novel. Sandy is encouraged in his betrayal by Bess’s sister Evelyn, who eventually marries the Rabbi Lionel Bengelsdorf, a collaborator who runs the OAA (Office of American Absorption), managing the Jewish Question for the Lindbergh administration, including policies of assimilation and resettlement. Alvin, a cousin who had been orphaned as a young boy, radicalized by Lindbergh’s election, joins the Canadian army to fight the Nazis in Europe, losing his leg in the process. Philip stays loyal to his father and mother, but his world is structured around childhood beliefs and a series of picaresque misadventures, so his reaction is the most confusing and at the same time the most poignant.

When Alvin returns after a long recovery in Canada, he moves into the Roth home, taking a room with little Phil, replacing Sandy, who moves into the family parlor. As one would expect of a little boy, Philip alternates between feelings of revulsion and fascination over Alvin’s missing limb. He also believes the house has become haunted for any number of reasons. He resolves to be a good kid:

One evening a few days before Alvin’s scheduled return I shined his pair of brown shoes and his pair of black shoes, ignoring as best I could any uncertainty I had as to whether shining all four of them was still necessary. To make those shoes gleam, to get his good clothes clean, to neatly pile the dresser drawers with his freshly washed things—as all of it simply a prayer, an improvised prayer imploring the household gods to protect our humble five rooms and all they contained from the vengeful fury of the missing leg (132-33).

Philip understands why he has to share a room with Alvin even though he would have preferred the parlor. “But how possibly could Sandy, who was now working for Lindbergh, share a room with someone who had lost a leg going to war against Lindbergh’s Nazi friends?” (133)

Alvin is broken. He no longer fulminates over Lindbergh and fascism. His prosthetic and the stump of his leg dominate his everyday life. Because of a bad fitting prosthesis, the site of his amputation continually breaks down:

“Is it healed?” I asked him.

“Not yet.”

“How long will it take?”

“Forever,” he replied.

I was stunned. This is endless! I thought.

“Extremely frustrating,” Alvin said. “You get on the leg they make for you and the stump breaks down. You get on crutches and it starts to swell up. The stump goes bad whatever you do” (136-37).

Eventually Philip becomes invaluable to Alvin, dressing the leg every day for him, the leg that will never heal. Alvin’s Sisyphean labors over his lost leg are a metaphor for the unalterable losses of the family and their world, the trauma that will forever haunt them in the aftermath of the Lindbergh administration. From Philip’s perspective the missing leg is another part of an enchanted world full of menacing specters. What else can explain all of these extraordinary events, these ruptures tearing at the peace and safety of his childhood? For a time, living with Alvin and nursing his wounds gives Phil purpose, but this isn’t the kind of structure a child needs. It’s a structure that develops from dealing with trauma, coping with the continually unexpected and the continually breaking down. It leads to fantasies. Philip’s sense of haunting only expands. He comes to believe that the ghosts of dead and vengeful extended family members have it out him from down in the cellar, which suggests that he owes them something, that he is guilty of some kind of betrayal.

The downstairs neighbors—the Wishnows, Mr. and Mrs. and their son Seldon—become part of the madness. Mr. Wishnow is dying, and his cancerous coughs only punctuate the fear of the space: “a cough that sounded from the cellar as though he were being ripped apart by the teeth of a two-man saw” (140).

Political activism ended, Alvin eventually falls in with a group of local ne’er-do-wells, but the FBI nonetheless pursues him relentlessly. They ruin what little life he has left in Newark, but not before Philip’s fantastical world reaches a fevered pitch of paranoia. He encounters Alvin shooting dice on the street and while fascinated, as boys understandably are with the illicit world of men, he laments what has become of his cousin: “as I watched him now in the clutches of his inferiors, and remembered all that my family had sacrificed to prevent him from turning himself into a replica of Shushy [Margolis, a local gangster], every obscenity I’d learned as his roommate flooded foully in my mind” (162). Alvin wins a good pile of cash and gives Philip two ten dollar bills, an extraordinary amount of money for a boy of nine in 1942.

As he makes his way home, an FBI man moves in beside him, asking him questions. As the agent asks him what the dice-shooting men were talking about, he thinks about the twenty dollars. A steady beat of leading questions come from the agent, who shamelessly tries to glean information from a scared boy. His kindly façade is chilling:

“Call me Don, why don’t you? And I’ll call you Phil. You know what a fascist is, don’t you Phil?”

“I think so.”

“Did they call anybody a fascist that you remember?”

“No.”

“Don’t rush yourself. Don’t rush to answer. Take all the time you need. Try hard to remember. It’s important. Did they call anybody a fascist? Did they say anything about Hitler? You know who Hitler is.”

“Everybody does.”

He’s a bad man, isn’t he?”

“Yes, I said.

He’s against the Jews, isn’t he?”

“Yes.”

“Who else is against the Jews?”

“The [German] Bund.”

“Anyone else?” he asked.

Philip is smart enough to know that he should keep quiet at that point lest he incriminate his family: “‘Don’t talk,’ I told myself, as though a protected boy of nine were mixed up with criminals and had something to hide. But I must have already begun to think of myself as a little criminal because I was a Jew” (167).

This is the horrible magic of fascism. By a series of terrifying steps, it takes advantage of innocence, transforming it into criminality. It then marks a person’s very identity as illegal or illicit. This is also heartbreaking, because Philip had begun to think of himself “as a little criminal.” He was a good boy, but his moral universe was spinning into chaos as the unforeseen and the unprecedented became regular parts of his life. The missing leg wanted vengeance. The cellar was haunted. To be Jewish was a crime.

Philip runs home only to come upon police cars and an ambulance. Mr. Wishnow had killed himself. “But then I realized that the ghost of Mr. Wishnow would now join the circle of ghosts already inhabiting the cellar and that, just because I was relieved he was dead, he would go out of his way to haunt me for the rest of his life” (168).

In a moment of confusion, the boy’s guilt takes over completely. He sees not Mrs. Wishnow but his mother emerging from the house with the medics. He now believes his father has committed suicide, not Mr. Wishnow, “He couldn’t take any more of Lindbergh and what Lindbergh was letting the Nazis do to the Jews of Russia and what Lindbergh had done to our family right here and so it was he who had hanged himself—in our closet (169). From the vantage point of a child, the narrator thus collapses international events far away with immediate, intimate ones, appearing in the family home, “in our closet” a space of privacy and hidden things, now exposed for the world to know.

The memory of his father in his head at that moment is astounding. It connects the elements of Philip’s menacingly enchanted world, the guilt, the missing leg, Alvin, his father’s everyday kindnesses:

I didn’t have hundreds of memories of him then, I had just one, and it did not seem to me at all important enough to be the memory I ought to be having. Alvin’s last memory of his father was of him closing the car door on his little boy’s finger—mine of my father was of him greeting the stump of a man who begged every day outside his office building. “How you doin’, Little Robert?” my father said, and the stump of a man replied, “How you, Herman?” (169)

It’s deadpan and yet devastating stuff, some of the best in the novel. Philip collapses into sobs and then tries to tear himself from his mother’s embrace to go after the ambulance. His mother attempts to break the spell, but his cracked childhood universe is too persistent:

“It’s Mr. Wishnow—it’s Mr. Wishnow who is dead.” She shook me back and forth to bring me to my senses. “It’s Seldon’s father dear—he died from illness this afternoon.”

I couldn’t tell if she was lying to keep me from becoming more hysterical or if she was telling the wonderful truth (169).

I’ll quote the narrator’s account of what happens next. It sums it all up better than I can. It’s one of those really good Roth summings up, where the pace of the paragraph speeds up, unrelentingly breathless as the repetitions reach a climactic moment:

I didn’t know why Alvin was bad now instead of good. I didn’t know if I had dreamed that an FBI agent had questioned me on Chancellor Avenue. It had to be a dream and yet couldn’t be if everybody else said they’d been questioned too. Unless that was the dream. I felt woozy and thought I was going to faint. I’d never before seen anyone faint, other than in a movie, and I’d never before fainted myself. I’d never before looked at my house from a hiding place across the street and wished that it was somebody else’s. I’d never before had twenty dollars in my pocket. I’d never before known anyone who’d seen his father hanging in a closet. I’d never before had to grow up at a pace like this.

Never before—the great refrain of 1942.

The denouement of the section is a punch in the gut for its naiveté: “I remained in bed with a high fever for six days, so weak and lifeless that the family doctor stopped by every evening to check on the progress of my disease, that not uncommon childhood ailment called why-can’t-it-be-the-way-it-was” (172).

Touching as that is, reading these pages in November 2016, one realizes only too well that it’s time to grow up. Roth has set a trap. He suspends meaningful politics for the narrow world of a child’s reasonable desire for structure, here figured as nostalgia for the immediate past. I’ll continue next time with more on this idea and others as they appear in the novel.

[i] Philip Roth, The Plot Against America (Houghton Mifflin, 2004), 340-1. Succeeding references to the book in parentheses.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks so much for these wonderful reconstructions of the novel; you’ve picked out some stunning passages for reflection and weaved them together beautifully.

I was struck by the moment you zero in on regarding Phil’s admission that he has begun thinking about himself “as a little criminal” and felt that it had an echo of Huck’s “All right then, I’ll go to hell.” Both moments are almost paradigmatic instances of anagnorisis, of a recognition that the full weight of the prevailing “moral”/legal/political order is set against the boy’s natural inclinations. (I guess I’d read the passage in Plot as a little more defiant: Phil is affirming his Jewishness as much as he’s submitting to the state’s categorization of him as such–thus, “I must have already begun to think of myself as a little criminal because I was a Jew” becomes less an admission of guilt than an assertion of self-definition–”I *am* a Jew, so I guess that makes me a criminal.”)

Anyway, I really enjoyed these two installments, and can’t wait for more!

Thanks so much Andy. Your reading makes a lot of sense here. He is a kind of Huck figure sans Jim.( Or maybe Alvin is his Jim, at least for a little while.) I guess I thought him a little more confused, seeing how Phil is nine and Huck is around thirteen if I recall it right. The structure of that sentence only complicates the reading: “But I must have already begun” which is not necessarily a faithful reconstruction of Philip’s thinking there, but the adult narrator’s speculation about what he must have thought at the time. That probably supports your reading more than mine. It also helps that Philip decides to keep his mouth shut at that point, which is a defiant act in itself. That’s certainly Huck, as you say.

At the same time, Philip’s feelings of guilt are very real. This particular section shows how intensely Philip grieves for the loss of his world, his “childhood ailment.” This is how grief often works. The grieving parties feel guilty because they always wonder if they might have done something differently, that wishful naive hope that things could be different while knowing they can’t be. “Maybe if I had or had not done x or y the outcome would have been different.” It’s even more complex than that, because grieving generates bizarre strings/senses of causation. For example, the grieving party thinks, “if I had done x or y all that time ago (point a), maybe the outcome (point b) would have been different,” as if any number of contingencies in between point a to point b didn’t have a much greater effect on the outcome. As a child, Philip’s sense of being haunted, of spectral vengeance, suggested to me that he’s set up to believe that things are his fault somehow. Possible strands of causation are everywhere in his world. After all, he’s haunted by his Jewish ancestors from the cellar. In his typically wicked sort of way, Roth could be playing around with a stereotype here. In other words, maybe it’s a bit of both–self definition and a pretty intense sense of guilt.

I should add that I don’t necessarily think Roth is playing that stereotype inasmuch as he’s depicting a perfectly natural reaction of thoughtful children to household problems. Why are mom and dad fighting? What did I do? Maybe if I’m a good kid, bad stuff won’t continue to happen. This is why he polishes Alvin’s shoes. After all, he had already collaborated with Sandy by keeping his brother’s drawings of Lindbergh a secret from his parents.

Peter–Not surprisingly, perhaps,I hear echoes of EL Doctorow’s “The Book of Daniel” in your exchange with Andy Seal. First Daniel Isaacson refers to himself as a “little criminal of perception” and variations on his experience with illicit epistemologies. Second, Daniel is very conscious of the scary (to him) African American janitor and handyman who lives in the basement of the Isaacson’s house and with whom Daniel’s also scary grandmother has some communication. I’m not sure what to make of the parallels but they do allude perhaps to the various registers, the different levels of existence, a child, a Jewish one at that in a situation where to be a Jew is a risk, must operate in in a predominantly white and Christian society. That’s awfully general, I know, but it’s an observation worth making. Can you make anything of it?

On its face the differences are striking. Paul and Rochelle Isaacson have a pretty tight circle of friends who are all Communists of one kind or another and who live essentially apart from their own community. Daniel’s father bombards him with lectures designed to expose capitalist perfidy at the level of culture, “teaching him how to be a psychic alien” (34). The Roths on the other hand are very much a part of their larger community. At one point in the novel, we get a sense of just how robust Bess Roth’s civic engagement was. We also get this early in Plot:

[Lindbergh’s] nomination by the Republicans to run against Roosevelt in 1940 assaulted, as nothing ever had before, that huge endowment of personal security that I had taken for granted as an American child of American parents in an American school in an American city in an America at peace with the world. (7)

Lots of “Americans” there. It takes an extraordinary event for Philip’s Jewishness to become essentialized in a white Christian nation, or rather, for the family to become fully aware of that essentialism. Lindbergh’s fascism dredges up long held prejudices in a white Christian nation. On the other hand, by the time the Isaacsons become notorious during the height of the Cold War, their Communism can’t be disentangled from the widespread anti-Semitism of a white Christian America, to use an anachronism, Richard Nixon’s poisonous comment that “the Jews are born spies.”

So it’s interesting that both children see themselves as “criminals” in one way or another. Daniel, as “the little criminal of perception” can view his parents in the way that a writer might. What I mean here is that kind of misanthropy that’s necessary in good writers, to see first the flaws of the subjects portrayed, particularly their base physicality, their limits and everyday peccadilloes. His crime stems from his refusal of idealism. Philip’s criminality is different. It’s the illicit world of childhood adventures, the thrill of breaking little taboos, say, rooting around in Earl Axman’s mom’s underwear drawer. Philip commits “crimes” when his “normal” childhood is disrupted. Daniel commits “crimes” by exposing the very normal underbelly of his parents’ extraordinary ideological commitments.

For Paul Isaacson, Williams (the super who lives down in their cellar) is an abstraction, a victim of exploitation, who, like Daniel’s grandmother, is also a victim of history, doomed: “he said Williams, the janitor in the cellar, was a man destroyed by American Society because of the color of his skin and never allowed to develop according to his inner worth” (35). How’s that for condescension! How can his parents ever have a genuine relationship with Williams under those assumptions? So in a way Williams, from down in the cellar, haunts Daniel, as does his grandmother. The super shares Daniel’s grandmother’s judgment of her daughter and son-in-law, who would deny the deeper history of life, symbol, and ritual that allowed her to live with suffering. As Williams puts it, “she [grandma] was the class of the house.”