As promised, today we’re back to the apocalypse. Specifically, I’m going to discuss the sometimes not-so-secret glee that some people feel when Everything Is Awful and Getting Worse, because to them that’s a sign that a final, cataclysmic deliverance from evil is right around the corner.

Perhaps the most prominent example of this kind of thinking in American culture today – this “cosmology,” to borrow a page from Robert H. Abzug’s marvelous conceptualization of how religious views thoroughly informed various 19th century American reform movements – is Dispensationalism of the sort most recently popularized in Tim LaHaye’s Left Behind series.

I say “Dispensationalism of [this] sort” here because there is not a single, “correct,” “orthodox” Dispensationalist theology – one needs a magisterium (or at least an ecumenical council or synod) for that, and despite the best efforts of Lewis Sperry Chafer to establish such a center of authority in Dallas Theological Seminary, there is in fact no central Dispensationalist body to adjudicate between competing schema of the End Times.

However, a Dispensationalist cosmology, broadly construed, has profoundly shaped not only American evangelicalism but also American politics and foreign policy. The book to read on this is Matthew Sutton’s American Apocalypse. (Also crucial: Paul Boyer’s When Time Shall Be No More.)

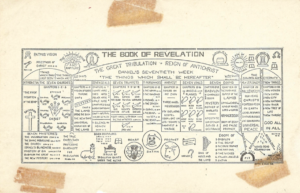

A chart from “Revelation Scripturally Illuminated,” published by the American Prophetic League in 1938 (click for full-sized image). As a kid, I taped this very chart inside my copy of the Scofield reference Bible.

Today I’d like to call your attention to two axioms of Dispensationalism, broadly construed: pre-millenialism and the idea of the rapture.

To adequately describe pre-millennialism requires some description of millennialism or millenarianism. In terms of American cultural history, millenarianism was the belief that it is the job of the Church to prepare the way of the Lord by making society more just, more holy, more loving – more Christian – until finally Christ himself comes to reign on the earth. Basically, millenarians sought to hasten the coming of the Lord by making everything better.

Pre-millennialism, on the other hand, was the belief that society would become more and more wicked until finally God’s judgment rained down upon humankind in a cataclysm of holy wrath, and then Christ himself would come to reign on the earth. Pre-millennialists, dismayed at the wickedness and decay of society, sought to hasten the coming of the Lord by preaching the gospel to the ends of the earth, since Jesus himself had said, “this gospel of the kingdom will be preached throughout the whole world, as a testimony to all nations; and then the end will come.” Pre-millenialists were not sanguine about the possibilities of reform.

As Abzug’s Cosmos Crumbling makes clear, both of these “millennialist” conceptions of the trajectory of human society were operating at the same time. In fact, his first chapter concludes by noting that over the course of his career as a social reformer Benjamin Rush moved from millenarian optimism to pre-millennial pessimism. Both conceptions of the cosmos were available and viable.

Dispensationalism draws from the well of pre-millennial eschatology. But Dispensationalism adds something to the water: the idea of the Rapture. This is the notion, first articulated by John Nelson Darby, that Christians (the “true Church”) will be removed from the earth and spared from experiencing the full measure of God’s wrath. This is a little bit of inside baseball, but it’s worth noting: there are some Dispensationalists who draw a distinction between “the Tribulation” and “God’s wrath,” and who thus believe that even true believers will go through part of the Tribulation, and then be caught up to safety before the final blow of divine judgment. And so there is quibbling within Dispensationalist circles about whether the Rapture will be “pre-trib,” “mid-trib,” or “post-trib.” But there’s no quibbling about this idea: true Christians will be spared from going through the very worst judgments that yet await humankind in this life, on this earth. (Christian ideas about the afterlife are another story.)

Now, putting on for just a brief moment my rarely-used but incredibly handy Christian theologian hat, here’s what I’d say about such a theology, speaking as a sometime “insider”: whatever this teaching may be, it is not the word of the cross. The hope (or “mournful awareness”) that, though others will suffer in this life, I will be spared mortal pain and peril in this life because I am a True Believer is, from this sometime Christian’s perspective, one of the most monstrously un-Christian things it is possible to believe. (And, just for good measure, while I’m at it, when it comes to ideas about divine judgment after death, apokatastasis is the way to go. And yes, I am aware that Origen was a heretic. Take a number.)

Okay, now I’m going to take off my Christian theologian hat and put on my intellectual history hat again – at the jaunty, rakish angle that suits me best – and say a few words about the this-worldly consequences of Dispensationlists’ confidence in the Rapture, which amounts to the confidence that, whatever happens in the geopolitical landscape, they will be miraculously delivered from suffering the worst of it. Indifference to worries or warnings about climate change has been one such consequence. Another such consequence, it seems, was the willingness of many “End Times”-aspirant voters to pull the lever for Donald J. Trump, because a vote for Trump would hasten the apocalypse.

Of course, it’s not “the apocalypse” or God’s wrath per se for which Dispensationalists hope (or so they would tell you); it’s the glorious reign of Christ, the fulfillment of the eschaton, the final fruition of God’s plan for the cosmos, a new Heaven and a new Earth. The apocalypse – including that nasty little bit about God’s wrath poured out upon the earth upon which we all live – is just a necessary and painful step (painful for some!) on the way to ultimate blessing for God’s chosen ones (among whom Dispensationalists count themselves).

So, for some evangelical Christian voters, there was no contradiction between voting for the arguably immoral and un-Christian Trump and seeking God’s will in the world. (And yes, I am personally acquainted with people who believe this way and who voted this way.)

Instead, doing their part to elect Trump was their opportunity to participate in God’s plan by helping to bring about the cataclysmic destruction of the old order, a painful but necessary step to pave the way for the subsequent eternal age of peace and plenty.

I believe that’s called “heightening the contradictions.”

Thanks, but no thanks, burn-it-all-down apocalypticists. While we’re working toward a more just society, some of us have to live here.

22 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Ah, the glaring hubris, perverse pleasure, and utter insanity that arises from claiming to know the mind of God (and hence what God wills) so that one can assist the deity in carrying out foreordained plan. A knowledge dependent in the first instance on texts penned by all-too-human hands, the most notorious in this regard being the book of Revelation, a book that effectively trumps the core Gospel teachings on love and morality (involving the Golden Rule and the double commandment of love, for example) for these putative Christians. See, for example, Adela Yarbro Collins, “The Book of Revelation” in The Encyclopedia of Apocalypticism, Vol. 1, edited by John J. Collins (New York: Continuum, 2000): 384-414. On the other hand, I read a few (thus not many) Leftists during the presidential campaign shamelessly indulging in a similar albeit secular variation on this apocalyptic rhetoric, believing that Trump’s victory will hasten the dissatisfaction with neoliberalism and magically turn the masses leftward.

Indeed. It’s probably a toss-up as to who would be more offended by the implicit comparison: do Dispensationalists resemble those among a certain subset of radical Leftists, or do those among a certain subset of radical Leftists resemble Dispensationalists? This is where “sensibility” really comes in handy!

Loved this piece. Just to note, your argument is closely related to Matt Sutton’s in American Apocalypse; I imagine if he’d commented publicly on the election, he’d be in substantial agreement with you.

Thanks Jeremy. I should note: though I mentioned Sutton’s book above as the book to read on the diffusion of Dispensationalist thinking in American politics/policy, I have not myself read it. (So you see, contra my recent personal blog post, I have mastered one of the Ways of Reading that they should be more explicit about in graduate training!) My read of contemporary Dispensationalism above is, I suppose, what you’d call an “internalist” account. But I’m glad to know that it squares (at least to some extent) with Sutton’s more capacious, deeper and more detailed treatment.

I “love” Christians who aren’t fundies or conservative evangelicals labeling a “doctrine X,” whatever it may be, as “unChristian.” (It’s like claiming Trump isn’t a real American, when actually, albeit somewhat of a caricature, he is very much a real American.)

Paul mentions the Rapture, followed by a pseudepigraphal writer in 2 Thessalonians referring to the man of lawlessness.

Although not involving a Rapture, the early Latin Christian church Father Tertullian, circa 200 CE, described one of the delights of heaven as being able to watch the sufferings of the damned in hell.

Sorry, folks, but Rapture talk is as much real Christianity as Donald Trump is a real American.

Glad you enjoyed the post.

One certainly can, from either an emic or an etic perspective, argue for a normative conception of what it means to be a Christian, involving, say, the sincere endeavor to follow the teachings and life (little evidence of the regarding the latter) of Christ as found in the synoptic Gospels, and thus from such a perspective, one can call a belief or practice “un-Christian” to the extent it departs in large measure from that normative conception. Of course for largely (historical and sociological) descriptive purposes, “Christians” are as we find them self-described and self-defined on the ground as it were. For one such normative conception, please see Anna Wierzbicka’s marvelous study, What did Jesus Mean? Explaining the Sermon on the Mount and the Parables in Simple and Universal Human Concepts (Oxford University Press, 2001).

sorry for the two typos in my posts above

I’m wondering if part of the attraction to apocalyptic dispensationalism (or, as SocraticGadfly intimated, religious theism in general) is the notion that a “sentencing” or “judgment” by a particular, concrete person/personality (God) is what initiates the fury (even if the earthly events in question are—from one causative angle—set in motion by human agents)?

Did the emergence of interdependence and bureaucratization allow for a nostalgic “back to basics” approach in human relationships to take root in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century versions of this theology? Something like: “You screwed me; I know it was you (not an impersonal process or force); I get to see ‘justice’ enacted.” It may be why other conceptions of the afterlife have not played as prominent a role in public discourse.

[Also with theologian hat on] I’m thinking of C.S. Lewis and his idea in The Great Divorce that people’s imaginings of this post-human reality might be alternatively narrated like their experiences of high-school cliques: jocks want to be with jocks, nerds with nerds, etc. It seemed like his idea (it’s been a while since I’ve read it) is that the “great divorce” is not persuasive because of legal tropes condemning or sentencing individuals borrowed from common-law traditions spanning different cultures and times, but merely natural inclinations to separate from people who don’t share their views about what eternity (or the new reality) should entail? Maybe this sentiment is shared by both Trump and Clinton supporters, although that was typed tongue-in-cheek.

Patrick, no worries on the typos — “for all have sinned [insert droning voice of junior high youth group leader here regarding the definition of “sin” as an archery term meaning “missing the mark] and fall short of the glory of God.”

😉

As to your larger point — certainly such an approach is possible, and if someone were to read that particular paragraph in my above post as a key point in my larger argument (rather than as a personal aside), that’s a fair enough reading. (However, it looks like someone didn’t read the post’s rather careful distinctions with much care. It happens.)

Dispensationalist thinking about being spared suffering in this life is not of a piece with Tertullian’s (quite familiar) writing (the first in a long line of such, um, affirmations in the history of Christian thought) about the satisfactions of watching the damned suffer in hell for eternity. The self-congratulatory impulse, of course, is evident in both; but a key difference, particularly interesting for an historian of thought, is the Darbyite innovation of transposing the assurance of deliverance, the assurance of being spared the suffering due to the damned, from the afterlife to this life. Indeed, off the top of my head, I’d say that the doctrine of the Rapture is an historical response to the disenchantment of time. It’s perhaps not the most famous such response, but in these days it may turn out to be the most influential one.

In any case, the “heighten the contradictions” crowd, whatever apocalyptic fantasies they entertain about how it’s really Good Theology (or Good Politics) to purposefully bring about a situation in which other people suffer, may see some of their wishes granted.

Mark, sorry, I missed your comment above — I guess yours went up while I was typing mine.

I think the timing of Darbyism in the 19th century is important, and is related to industrialization — but being invested in God’s divine judgment being visited upon one’s enemies (and even constructing elaborate narratives about the same!) is hardly new in the 19th century. But, as I said above, I would guess that the Rapture — physically removing “the church” from historical time (and all the misery that goes with it) while historical time is still unfolding — is partly a response to (a marker of?) the disenchantment/desacralization of time. But that conjecture re: explanation for the 19th century origins is very off-the-top-of-my head.

On The Great Divorce — it has been a while since I’ve read it as well, but IIRC the basic argument is basically a reading of predestination through the lens of free will (or vice versa), so that “the eternal decree of God” is at the same time “the freely chosen path of the unrepentant soul.” Lewis is big on theodicy, as anyone who wants to stick to the idea of an eternal hell would need to be. (On the flip side, arguing against the idea of an eternal hell also requires a theodicy of a different kind.)

L.D. — that said, the “rapture” doesn’t preclude a pre-Trib take, if 1 Thessalonians 4 is read in light of 2 Thessalonians 2, which I noted before the Tertullian comment.

That doesn’t mean such an interpretation is correct, but I’ll stand by it not being wrong.

Oh my gracious.

I’m sorry, but this is just not going to happen at the USIH blog — not with me, anyhow.

Unfortunately for me and you both, “Socratic Gadfly,” I am exceedingly well acquainted with both the exegetical arguments for the Rapture as a “biblical doctrine” and the proof-texts on which those arguments are based. I mean, is there some part of as-a-kid-I-taped-this-chart-of-the-End-Times-inside-my-Scofield-Bible that you missed? If so, you’re welcome to go back through my past posts at this blog (way, way back) and learn a great deal (though certainly not everything!) about my background as a Fundamentalist Dispensationalist.

As to my expertise in Biblical exegesis, Christian theology, and the history of theology (different things!) as matters of study (and, as a side note, it is worth affirming: such expertise is accessible to anybody, whether or not they have any particular faith or not faith at all; as any intellectual historian would tell you, you don’t have to be a believer to study/understand beliefs) — well, I could whip out the transcripts, but a tree is known by its fruit, so I’ll let my engagement with these questions here at the blog speak for itself.

But if it helps you sleep at night, I am happy to affirm that many other people before you have found “the Rapture” they were looking for in the same Pauline epistles, as well as Revelation 1 (“I was caught up in the spirit…”), and various and sundry other passages “read in light of” each other, and I have no doubt that your interpretation is just as solid as theirs is.

L.D. I don’t know if it was your intention, but to this cafeteria catholic this post was one of the most Christian pieces of writing I’d read in sometime. Thank you. Also, Garry Wills Under God is great on this topic. Esp the chapters on Pat Robertson and coffee cup apocalypse..

Oh, Chris, that was not my intention. So “you’re welcome” or “I’m sorry” or both, as the case may be.

I haven’t read the Garry Wills book, but I’ll add it to the hopper. I’ll never get to put a syllabus together on this stuff, but I’m sure I’ll get to write about it again at some point in a more formal fashion. The post on Alas, Babylon! and this post are both cobbled together from the detritus of my current research concerns for the book revisions. I am going to leave apocalypticism behind in next week’s post though — no hell; just hope.

i am just getting to read this piece now, rather on the late side. It is so spot on, so accurate, so deeply informed about the craziness of certain sects of Christianity. I know, because they are in my family and among my friends growing up. Not enough people know about Darby, outside of historians of religion but the mantra of the true believers I knew back in the late 70s and early 80s was a solid and coherent political formula: low taxes, faith in business and entrepreneurship, and ever awaiting the coming rapture during which all would be made good. All these sentiments were made quite explicit. Too little is known about these beliefs and the political implications of them. Many thanks for putting this out there L D.

This notion that a vote for Trump is a vote for hastening a cataclysm–are there any links to any published comments to that effect? Moody, Charisma, something?

I know a whole lot of dispensationalists who voted for Trump, but I’ve never heard anything but the opposite rationale: Hillary is corrupt, she’ll destroy the nation, and also, Supreme Court justices!

Thanks Mitch. I could have done a better job of more explicitly tying my two “apocalypse” posts together — but this is blogging, so everything is still in solution and just beginning to form whatever precipitate will eventually emerge. But the selfishness at the root of Rapture theology, the assurance that the true believers need never face the destruction of this world, underwrites not just a reckless indifference to the this-worldly consequences of various courses of action (climate change, wars for oil, etc), but a zeal (among some) to actually exacerbate worldwide chaos and suffering in order to jump-start the “clock of prophecy.”

John, I linked a couple of articles in the story above, but here are a few representative samples:

Rabbi Predicts Trump Will Win and Usher in the Second Coming (Charisma News)

Here Is the Real Reason Why Donald Trump Was Chosen to Be the Republican Candidate for President (Now the End Begins)

“…the final TRUMP that makes the coming of the Rapture!” (discussion board thread)

L.D. — I have a graduate divinity degree, still know Greek halfway well, and read Hebrew and Aramaic, too.

I’m one of those atheists and agnostics who knows religion better than most Christians.

And, I’ll leave THAT there.

Well, since you speak of leavings, what is there to say but…Holy shit — this thread is just lousy with seminarians.

Super piece by Erin Smith up today at the NEH website with an article from the Winter 2017 number of Humanities, looking at the reception history of Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth and explaining (among other things) its escapist appeal to readers.

The Late Great Planet Earth made the apocalypse a Popular Concern