As I mentioned in my last post, the first, brief New York Times review of Sisterhood Is Powerful singled out for special praise “Naomi Weisstein’s classic ‘Kinder, Kuche, Kirche as Scientific Law: Psychology Constructs the Female,’ a devastating critique of sex-bias in experimental psychology.”

I was intrigued by the reviewer’s use of the term “classic.” How had Weisstein’s essay, originally read (per the copyright notice) at the American Studies Association at UC Davis on October 26, 1968 (Sisterhood 228), become a “classic” by 1970? A classic of what? A classic for whom? And Weisstein was a neuropsychologist — what was she doing at the American Studies conference anyhow? (I’m not complaining — just wondering!)

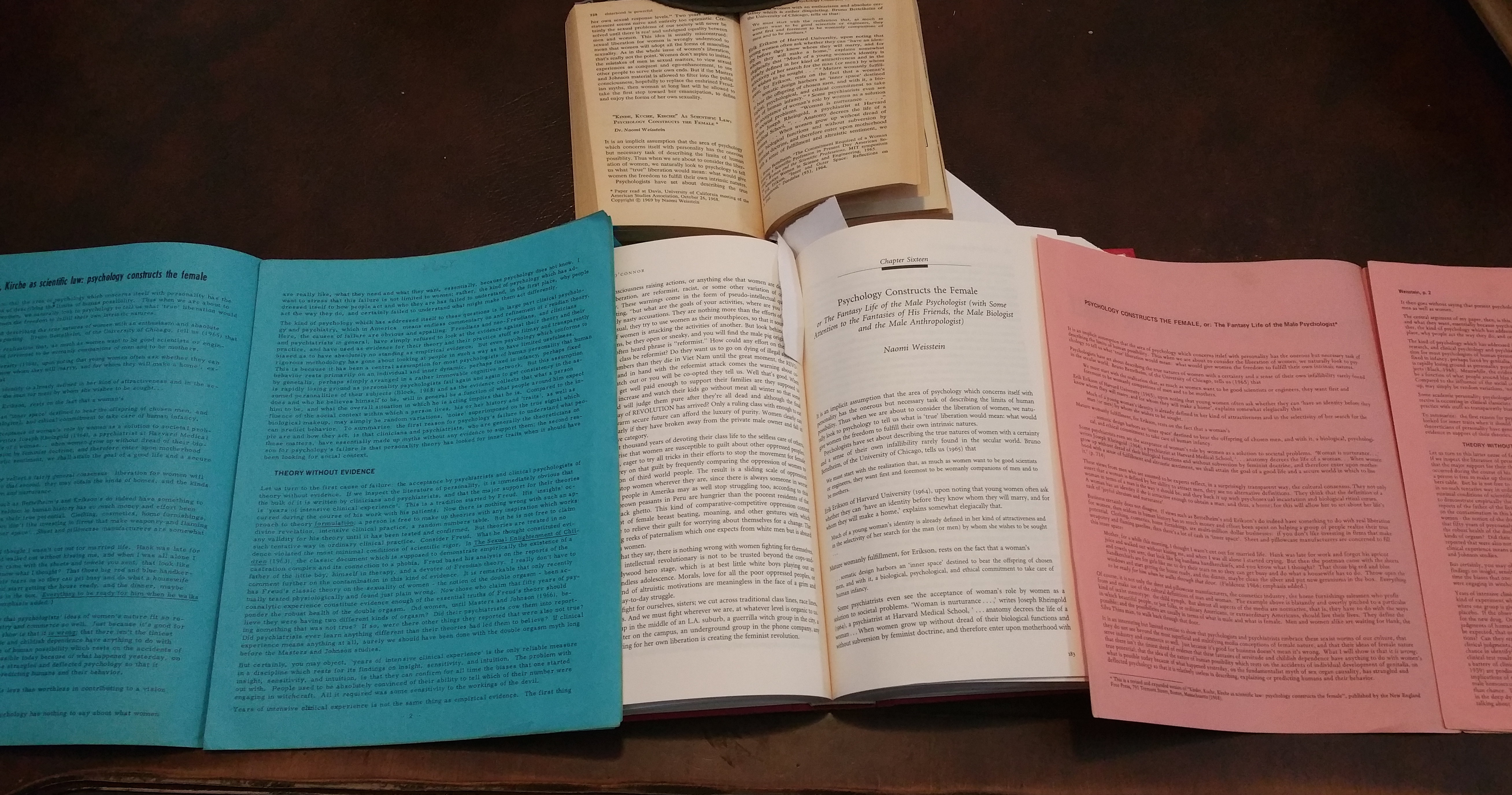

So I decided to try to find out what I could about the career of Weisstein’s essay apart from its anthologization in Sisterhood. As it turns out, that 1970 publication represented not only the first of multiple anthologizations of the essay but also one of the earliest of subsequent versions of the text itself. Many of those early iterations of Weisstein’s frequently revised and expanded paper – including what I understand to be the first version, the paper as presented at the American Studies conference and as anthologized in Sisterhood – were published and distributed by the New England Free Press.

In WorldCat and in online booksellers’ inventories, I found a variety of publication dates for Weisstein’s essay as a NEFP pamphlet, ranging from 1968 to 1971. However, some of the publication dates were bracketed and/or flagged with a question mark, indicating that no date itself was visible on the document.

What to make of this variety of dates associated with “Kinder, Kuche, Kirche as Scientific Law”? I wasn’t sure. So I dropped a line to my pal Jesse Lemisch, Naomi Weisstein’s life partner (now, sadly, her widower) asking if he could offer any more clarity on the publishing history of Naomi’s essay as a pamphlet, and how that publication related to the timing of the essay’s appearance in the 1970 anthology. He offered what information he could recall, and put me in touch with Jim O’Brien, a New Left historian and activist and longtime editor/publisher at the New England Free Press.

So I wrote to Jim, and while waiting for a reply I whipped out my trusty American Express card and ordered a couple of NEFP-published versions of Weisstein’s essay from a few online booksellers.

That was a good call.

It’s one thing to read about the importance of ad hoc publishing co-ops, to read about how the feminist movement got its start with typed manifestos circulated hand to hand or run off in small batches on kitchen-table mimeograph machines. It’s another thing to actually see and handle and examine some of these crucial early productions, these ephemera that nurtured a formidable and enduring movement.

As originally printed, “Kinder, Kuche, Kirche as Scientific Law” cost just 10 cents. It’s an 8-page pamphlet, printed on two 11×17 sheets of paper, folded but not saddle-stapled. As the cover blurb notes, the article was “one of a series on women’s liberation chosen by a group of Boston-area women and published by NEFP.” I presume these are the same “Boston-area” women responsible for producing Our Bodies, Ourselves, another title produced and distributed by the NEFP.

I asked Jim O’Brien to tell me a little more about the production process at NEFP. He wrote: “Most of the printing was in-house (we had two sheet-fed offset presses, the larger of which printed sheets 17 1/2 x 22 1/2 inches).” The Weisstein essay would have been one of those in-house jobs. However, he added, “A few of the biggest pamphlets were farmed out, most notably Our Bodies Our Selves, of which the Free Press distributed something like 200,000 newsprint copies before it was published commercially by Simon & Schuster.”

But when exactly was “Kinder, Kuche, Kirche as Scientific Law” printed? If NEFP produced the pamphlet in 1968, could it have been produced before Weisstein read the paper at the American Studies conference? That seems unlikely, as most NEFP publications were reprints, and the cover note of this pamphlet specifies that it was “chosen” by that group of Boston-area women (likely the same ones behind Our Bodies Our Selves). In the introduction retrospective roundtable on Weisstein’s essay, published in 1993 in Feminism & Psychology (3:2), Celia Kitzinger notes that Weistein presented her paper not only at the Davis conference in 1968, but also at a feminist conference at “Lake Villa, Illinois earlier that year” (Kitzinger 189). But other sources place the timing of the Lake Villa conference as November 1968 (see, for example, “Our Gang of Four: Friendships and Women’s Liberation,” by Amy Kesselman with Heather Booth, Vivian Rothstein, and Naomi Weisstein, originally published in 1999).

Bottom line: either as a result of the extraordinarily enthusiastic reception Weisstein’s paper received at the American Studies conference (when her presentation concluded, she received a standing ovation) or as a consequence of the impact her paper had at the Lake Villa meeting, this paper delivered in late 1968 had made enough of a splash to be selected as a crucial text for the nascent women’s liberation movement and was apparently in press, if not in print, by December 1968. Thus Weisstein’s essay, delivered as a spoken address, quickly gained esteem and broader acclamation as a widely-circulated written text. The 1970 Sisterhood anthology reproduced verbatim the text of that 10 cent basement-printed brochure.

Though the reputation of Weisstein’s sharp, insightful essay was apparently well-established in the women’s liberation movement, the essay itself was not yet finished. Naomi Weisstein revised and expanded her original work, republishing the updated edition in 1970 under a slightly different title: “Psychology Constructs the Female; or, The Fantasy Life of the Male Psychologist.” This pamphlet too was printed and distributed by the New England Free Press. A note inside the front cover inidicates that the essay was “a revised and expanded version” of the earlier piece originally published in 1968. This expanded version of Weisstein’s essay is probably the version anthologized in 1973 in Radical Feminism, edited by A. Koedt, A. Levine, and A. Rapone (New York: Quadrangle Books). In that anthology, the title of the essay was further expanded: “Psychology Constructs the Female; or, the Fantasy Life of the Male Psychologist (with Some Attention to the Fantasies of His Friends, the Male Biologist and the Male Anthropologist).”

I say “probably the anthologized version” because I have yet to come across a copy of the 1973 anthology. However, permissions notices in the appendix of Radical Feminism: A Documentary Reader, edited by Barbara A. Crow (NYU: 2000), indicate that the Weisstein essay excerpted in that collection was taken from the 1973 anthology. And the text reproduced in the 2000 anthology matches up with the 1970 leaflet printed by New England Free Press. [UPDATE 2/25/17 7:00 AM: No, I have looked again through the 1970 pamphlet and the Radical Feminism anthology version; they don’t match. The anthologized version from 1973, reprinted in 2000, was expanded/updated again after the publication of the 1970 pamphlet.]

And what does all this mean? What does all this tell us? Why does any of this matter to me or you or anyone else?

Well, in terms of the publishing history of this essay, I’ve only sketched out what I can tell from the sources that are available to me; I’m sure there’s more to be said about it, and consulting the papers of Naomi Weisstein at the Schlesinger Library wouldn’t be a bad place to start. But even this incomplete history can tell us a number of things.

For one thing, this history points to the fluid boundaries between feminist theory and political practice inside and outside of the academy. A sharply argued paper presented at a scholarly conference doubled as a spirited rallying cry for a group of women gathered to strengthen one another and strategize about the possibilities for liberatory practice and politics.

The history of Weisstein’s frequent reconsideration and revision of her original paper — and the fact that those revisions found broader and broader audiences — points not to a paucity of material for inquiry but rather its seemingly endless abundance. That Weisstein returned repeatedly and fruitfully to her critique of science’s gendered constructions demonstrates the importance of the task she had undertaken. Her repeated skewering of the epistemic arrogance of the (male dominated) human sciences as purporting to know much about human nature while not recognizing the human flaws in their own systems suggests there was much in need of critique.

And, as her various titles for this essay suggest, Weisstein’s critique was always delivered with a comic edge. In an interview with Celia Kitzingen (p. 191), Weisstein had this to say about her comic approach:

Comedy is a beautiful way of equalizing power in the most intimidating of circumstances, and it should be deliberately and consciously used by us. I’ve always tried to make my scientific presentations — well, all my talks — funny. When you are doing insurgent science, that is, you are dissenting from the reigning theories, you have to challenge them with more than just the truth of your findings if you’re going to be heard. You have to challenge the theater of science, its authoritarian grandeur and elitist majesty.

Should I ever come across authoritarian grandeur and elitist majesty in some other field of academe (can’t imagine where else one might encounter such things, but you just never know!) — well, now I’ll know what to do.

Finally, the publishing history of (at least some) of Weisstein’s many revisions — their quick and widespread availability, from her pen to readers’ hands in a matter of weeks — also points to the crucial role played by the self-publishing and small-publishing grassroots operations in the work of nurturing and circulating ideas. This was especially true of the New England Free Press. A sidebar from the April 25, 1970 edition of off our backs (itself a home-grown print production) contained the following item under “media”:

The New England Free Press is interested in training movement people, especially women and community organizers, to be movement printers. The workshop is filled for the summer, but people can send in their names now for places in the fall.

The time needed to learn to print is 2-3 months. The Free Press cannot provide room and board, although it is possible that women in the women’s liberation movement in Boston may be willing to put people up.

People in the program will be trained in all the skills related to printing including: layout, offset camera work, plate burning, printing, folding, etc. If you are interested call or write: Printing Workshop, New England Free Press, 791 Tremont Street, Boston, Mass. 02118.

This may be publishing history or book history, but it is surely also the history of ideas: the belief that an alternative politics required an alternative press, and the conviction that volunteer writers, newly minted activists, first-time editors, and inexperienced publishers had the right and the duty, the means and the mission to marshal basement printing presses and living-room mimeograph machines in a struggle for social and political transformation.

In my next post in this series, I’m going to say a little bit more about the New England Free Press, specifically about its role in supporting the Radical Historians caucus and providing an outlet for the publication of one of the most incendiary papers ever presented at the American Historical Association, a 1970 tour de force indictment of sexism in the historical profession, penned by Linda Gordon, Persis Hunt, Elizabeth Pleck, Marcia Scott, and Rochelle Zeigler.

In the meantime, I am delighted to report that my wonderful new friend Jim O’Brien has generously offered an original work of his own to share with our readers here: a participant-observer’s historic account of the New Left and of the work of the New England Free Press in supporting radical political movements on and off campus. I will be publishing that work in a separate series of posts here at the blog. It’s an important eyewitness account, and I’m very grateful to Jim O’Brien for agreeing to make it available here for historical research.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

As indicated in the body of the post above, I have updated it. After a more careful (read: fully caffeinated) comparison of the 1970 pamphlet and the version in the Radical Feminism anthology, I saw that they were not, in fact, the same iteration of the essay. If it was anthologized between ’70 and ’73 — and I am guessing it must have been, for this essay was indeed a “classic” in the Women’s Liberation Movement — then the ’70 pamphlet might have its counterpart in a paperback or hardback collection.

Thanks for sharing this great detective work. This post makes a familiar text feel new again. I have taught the Weisstein article a number of times in my history of psychology seminar. I tend to give my students the Feminism & Psychology reprint, but this often results in them mistaking it for a 1990s text. This a great example of how a material culture approach can inform intellectual history.

LD: Nice! I love book history work. …I detect a conference paper brewing for SHARP?! – TL

That’s kind of you, Tim.

But there’s only one conference on my mind right now: USIH 2017 in Dallas. At this point I don’t have any plans to be on the program, but the program will definitely be on me! So I’m grateful for my colleagues on the planning committee, and we are all excited to see the proposals that are coming in.

In an act of sheer faith, I proposed something for AHA 2018 — whether the panel is accepted or not, putting together the proposal itself was my way of affirming that there’s going to be life on the other side of planning USIH 2017.

As to this particular line of inquiry (the book history + feminist history combo, focused particularly on texts from the 1970s), it will definitely be interleaved into my revisions for this book that I am currently writing-via-worrying-about-not-writing-but-at-the-same-time-blogging-as-a-way-of-tricking-myself-into-writing. As one does.

So, to sum up: USIH 2017! It’s happening! And…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XZGwHtGBZJU