In this post, and in a few follow-up posts, I’m going to look at the publishing history of some primary sources from the feminist movement(s) of the 1970s. It may well be that “book history” is not quite the same thing as “intellectual history” or the “history of ideas.” But when I am trying to hammer out my own ideas about the ideas I encounter on the page, it sometimes helps me and always cheers me to pay some attention to the page itself, which is as much a manifestation of human thought as the words upon it.

Do the words upon the page mean something different when I have a better sense of the history of the page itself? Sometimes they do. But even when my expeditions into the material world of texts don’t yield findings that are significant to my project (significance is never absolute; significance is only assessed in relation to something else), the excursions themselves are always pleasant. So come along with me and let’s see where the path takes us.

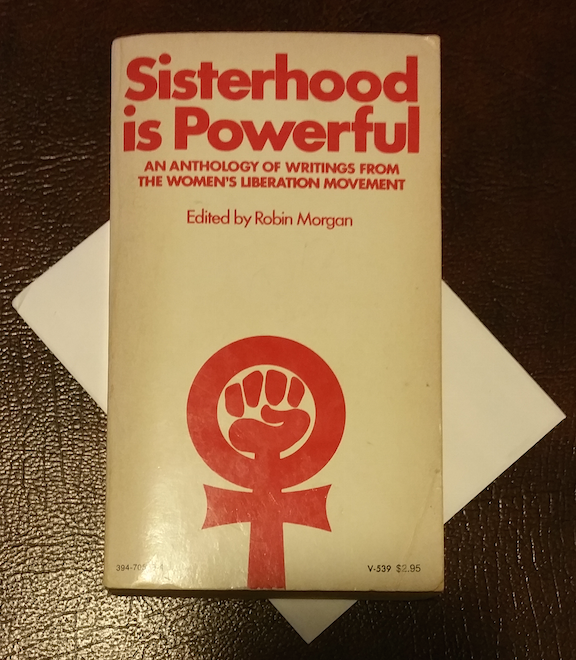

The first source I want to look at is the groundbreaking anthology, Sisterhood Is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women’s Liberation Movement (1970), edited by Robin Morgan.

This book is no longer in print, but I found a used copy online – a hardback copy. When I posted a pic to Facebook, my friend Monica Mercado, who teaches women’s history, was surprised to see the book in hardback. When she teaches the history of second-wave feminism, she points to Sisterhood Is Powerful as an example of the explosion of feminist texts published in paperback, making key ideas and expressions of the women’s liberation movement broadly accessible and easily affordable for a burgeoning audience of women readers who were educating themselves and each other about the feminist movement.

The history of Sisterhood Is Powerful as a mass-market paperback is a history of ideas that caught like wildfire, of a movement that exploded onto the scene and reached women in all walks of life.

But what is the history of Sisterhood Is Powerful as a hardback, and how is that edition of the book connected to the paperback edition?

The anthology was published simultaneously in hardback and paperback by Random House and its paperback imprint Vintage. According to their respective copyright pages, the Vintage paperback edition came out first (September 1970), followed by the Random House hardback (first printing: October 1970). But the advance publicity for the book apparently focused on the hardback edition.* In an August 17, 1970 feature article in the New York Times, “Women’s Lib Wooed by Publishers,” Grace Lichtenstein noted that Sisterhood is Powerful would be published as “a hardcover anthology,” while a similar project, Women’s Liberation: Blueprint for the Future, would be coming out in paperback.

Lichtenstein noted that booksellers were reporting “brisk” demand for works dealing with the women’s movement, and some Manhattan bookstores were even setting up special sections on feminism. “Apparently,” Lichtenstein observed early in the piece, “like student protest, black history and American Indians before it, the women’s liberation movement is about to have its ‘season’ in book publishing.” Indeed, a spokesman for William Morrow told Lichtenstein that Shulamith Firestone’s forthcoming work, The Dialectic of Sex, was to be “our major nonfiction for the fall.” Big houses and serious presses were putting their prestige behind “women’s lib” – or recognizing that a new work in that booming genre could enhance their prestige, market share, and bottom line.

But note some of Lichtenstein’s concluding paragraphs:

Regardless of how the spate of feminist books and magazines sells, male editors who have had to work with movement writers agree it has been a harrowing, yet rewarding, experience.

‘We fought, and of course they accused me of being a male chauvinist,’ said a laughing Erwin Gilkes of Basic Books, who is working with Misses [Vivian] Gornick and [Barbara K.] Moran [on another hardcover anthology, 51 Per Cent: The Case for Women’s Liberation]. “And I still am. One doesn’t undo 2,000 years of history. But boy, am I learning!”

Some women’s liberation books are selling despite what seems to be a lack of enthusiasm among the publisher’s sales representatives, most of whom are men, and bookshop owners. “We found a lot of resistance in the trade,” said a publicity director who did not want to be identified. “Some of our men find the subject distasteful.”

The man who reviewed the book for the New York Times may have been phased by the subject-matter of the anthology; but he was more bothered, it seems, by the price. John Leonard reviewed Sisterhood Is Powerful for the Times (“Adam Takes a Ribbing; It Hurts,” Oct. 29, 1970), along with The Dialectic of Sex, Women’s Liberation: Blueprint for the Future, and (oddly) Don’t Fall Off the Mountain by Shirley MacLaine.

Leonard led with the MacLaine book and explained his rationale for grouping it with the others:

Why include Shirley MacLaine’s autobiography in a round-up review of the latest texts on radical feminism? Because Miss MacLaine – and it is the style of this newspaper to use ‘Miss and ‘Mr.’ – deals with herself as a person, not a victim, not an abstraction. Her accommodations to stardom, marriage, motherhood and the mysterious East don’t add up to an argument or a slogan; they add up to something like a poem…

The aside about house style was, one supposes, a little dig at feminists’ concern for the ways in which language perpetuated patriarchy and imperiled women’s personhood. On the contrary, Leonard suggested, MacLaine is fully a person because she did not view herself as “a victim.”

Leonard spent three paragraphs on MacLaine, three on Shulamith Firestone (“a sharp and brilliant mind,” but one whose hostility to the nuclear family distressed him), and one paragraph on Sisterhood Is Powerful and Women’s Liberation:

‘Sisterhood’ is considerably better, if considerably more expensive, mostly because it includes Naomi Weisstein’s classic ‘Kinder, Kuche, Kirche as Scientific Law: Psychology Constructs the Female,’ a devastating critique of sex-bias in experimental psychology.

That sentence intrigued me – partly because I misread it at first. I thought Leonard was saying that Weisstein’s essay made Sisterhood considerably more expensive, and I wondered why that was so. But Leonard was saying that Weisstein’s essay made the anthology better than Women’s Liberation. But once I had properly parsed that sentence, I had solved one mystery only to confront another: how had Weisstein’s essay, originally read (per the copyright notice) at the American Studies Association at UC Davis on October 26, 1968 (Sisterhood 228), become a “classic” by 1970?

That’s a question I’ll explore in the next post.

___________

*The records of Random House have found a home at Columbia University. The 556-page finding aid includes a number of entries for the anthology – mostly, it seems, editorial correspondence with Robin Morgan. But it’s possible that there would be some discussion of publicity strategies in the collection.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this post–it has me thinking a bit about some of the sources I’ve been using for my dissertation. There, I spend part of my first chapter exploring the literature around black voting power as it was written about in books and magazine articles in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I’m intrigued by what’s published, by whom, and why–and your post reminded me why those questions always fascinate me.

I’m looking forward to the next installment! Reminds me that I need to post a picture of a beat up copy of Lerone Bennett’s “The Challenge of Blackness” I purchased from the internet over a year ago–reminds me a lot of your book.

Thanks Robert. It occurs to me that I actually didn’t say *much* in this post about the history of the book as a hardback, beyond noting it was promoted and reviewed. In advertisements for the book in the books section of the NY Times, Random House mentioned that it was available in hardback or paperback. And there was at least one book club who offered the hardback edition as a selection. But the fame of this book rests (rightly) on that mass-market paperback.

I had all three of Leonard’s review books in paperback in my bookcase. Your project coincides with the conclusion of a five-week course, History of Feminism, taught by Margo Horn at Stanford. I have studied First Wave feminism and have lived through Second Wave as an undergraduate and law student. It has been haunting to look back at that intense era through the eyes of my current younger classmates. We must seem as ancient to them as the First Wave seemed to me.

The physical feel of books, especially hardback books, was important in pre-Internet times. I grew up just three blocks from the local library, and while borrowed books were important, they lacked the significance of owning my own library that came with the explosion in paperbacks and trade books. Paperbacks were also an important way of connecting with feminist women.

Thanks for your thought-provoking post. I did buy Kate Millett’s book as a hardbound. I look forward to what you say about it.

Susan, thanks for your comment and for sharing your experience.

I should have said more in this post about the parallel careers of the hardback and paperback. I thought of adding some above, but it would be such a major edit that it would amount to a rewrite of this post.

Sisterhood was reviewed twice in the NYT — John Leonard reviewed it first, but a couple of months later Annie Gottlieb reviewed it, and she reviewed it as a paperback. I’ve written this up at my own blog (and included a screengrab of the Random House advertisement for the book): More on Sisterhood.

Thanks for reading — I probably won’t get to all the texts that mattered to people in this series, but I’ll look at some that were and probably still are important (especially for historians).

Minor point: the quoted Grace Lichtenstein article has a typo on the last name of the then-publisher of Basic Books (whose name I recognized from various ‘acknowledgments’ sections): it was Glikes, not Gilkes.

Google informed me that he died relatively young, in the mid-1990s:

http://www.nytimes.com/1994/05/16/obituaries/erwin-a-glikes-56-publisher-of-intellectual-nonfiction-dies.html

The name “Robin Morgan” reminds me of a bizarre publishing incident involving her which I only learned about while teaching a course on Sylvia Plath. In 1972, Morgan wrote a poem called “Arraignment” that was, as you note above, to be published simultaneously in HB by Random House and PB by Vintage Contemporaries in a volume called _Monster_. The poem is harsh: she accuses Plath’s former husband Ted Hughes of causing the deaths of both his first and second wives (both died by suicide, Plath in 1963, Assia Weevil in 1970, I think), of brainwashing his children, and of plagiarizing Plath’s imagery, among other things. The poem ends with the brutal image of a covey of women coming to Ted’s house, stealing his children (Frieda and Nicholas), cutting off his penis, stuffing it into his mouth, and blowing out his brains.

Needless to say, Morgan’s publishers were not keen on including this poem in the volume for fear of a lawsuit from the Hughes estate. Random House hemmed and hawed, and Morgan didn’t think the book would be published (and she needed the money, badly). Finally, to appease her publishers, Morgan produced a revised version of “Arraignment” that was slightly more tame. Still enflamed over the experience, she then sought a less commercially timid publisher to print the original version. _Ms._ magazine turned her down, and it was finally printed, along with an accompanying explanatory note, as “Conspiracy of Silence Against a Feminist Poem” in the _Feminist Art Journal_ in 1972. I had to have a librarian help me to track it down. It was also apparently printed in hand-made “pirated” versions created by women throughout the U.S. and the English Commonwealth, as Morgan relays on her website: http://www.robinmorgan.net/blog/book/monster/

In any case, I thought this would be an interesting anecdote to add to these reflections on the print history of feminism.