In previous posts I have looked at the publishing history of a couple of feminist texts: the 1970 anthology of women’s liberation writings, Sisterhood is Powerful, and Naomi Weisstein’s oft-revised-and-expanded “Kinder, Kuche, Kirche: Psychology Constructs the Female,” which debuted as a paper delivered at the American Studies Association conference in 1968. Today I’m going to look at the history of another feminist text that began as a conference presentation and was subsequently published, revised and reprinted under various titles: “A Review of Sexism in American Historical Writing,” by Linda Gordon, Persis Hunt, Elizabeth Pleck, Marcia Scott, and Rochelle Zeigler.

In previous posts I have looked at the publishing history of a couple of feminist texts: the 1970 anthology of women’s liberation writings, Sisterhood is Powerful, and Naomi Weisstein’s oft-revised-and-expanded “Kinder, Kuche, Kirche: Psychology Constructs the Female,” which debuted as a paper delivered at the American Studies Association conference in 1968. Today I’m going to look at the history of another feminist text that began as a conference presentation and was subsequently published, revised and reprinted under various titles: “A Review of Sexism in American Historical Writing,” by Linda Gordon, Persis Hunt, Elizabeth Pleck, Marcia Scott, and Rochelle Zeigler.

This co-authored paper debuted at the 1970 meeting of the American Historical Association; it was listed in the 1970 program under the title, “Sexism in American Historiography” (more on that title below), one of three papers presented on a panel entitled “Politics and the American Historian: How Liberal Scholarship Serves Capitalism.”[1]

The panel, chaired by Linda Gordon, was slotted in the last session of the last day of the conference – 2:30 p.m. on Wednesday, December 30. Here’s the panel description:

The work of many American historians is ideological: it has the effect (intended or not) of providing a justification of the American social system. The first paper demonstrates that textbooks used in freshman history courses present a defense of capitalist society. The second shows that the picture of woman’s role in history reinforces present-day male chauvinist attitudes and institutions. The third argues that liberal historians have obscured the fact that the “achievements” of western society have been based on the exploitation of the non-western world. One-half the session will be devoted to open discussion.

The first paper, presented by David Hunt and Peter Weiler, Gordon’s colleagues at the University of Massachusetts, was entitled “Indoctrinating Freshmen: Ideological Themes In Selected ‘Western Civlization’ Books.” A book-length version of this paper, co-authored by Hunt, Weiler, and Gordon, was published in the early 1970s by the Radical Historians Caucus under the title “History as Indoctrination: A Critique of Palmer and Colton’s History of the Modern World.”[2] It is worth noting that the “Palmer” referred to in this title, and in the paper, was none other than Robert R. Palmer, who was the president of the AHA in 1970. So, in terms of leveling critiques at the work of contemporary historians, this panel started off with a bang. I’d dearly like to know if Robert Palmer deigned to attend this session. I’m guessing not, but if somebody who was there wants to share their recollections, I’m all ears.

Following this critique of the AHA president’s Western Civ textbook, the five co-authors of “Sexism in American Historiography” examined recent works by male historians who, despite their varying points of view and avenues of inquiry, all had one thing in common: “a belief that anatomy is destiny, in short, sexism.”[3]

I don’t know how many of the authors mentioned in the published version of the paper came up for discussion in the 1970 presentation. But several of the authors critiqued in the published paper were also on the program at the 1970 AHA: Christopher Lasch, Carl Degler, David Potter, and William L. O’Neill. Again, I don’t know if any of those authors were in the audience for this panel, but I’d be interested to find out.

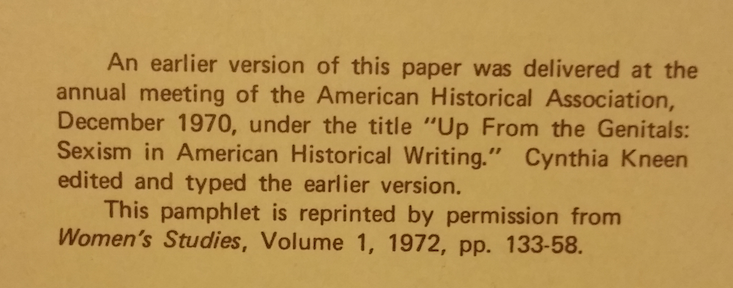

Here’s something else I don’t know: why this co-authored paper was listed in the 1970 AHA program under the short title, “Sexism in American Historiography.” For the copyright notice on the 1972 publication of the paper in Women’s Studies – as well as the copyright notice in the Radical Historians Caucus reprint of that article – reads as follows: “An earlier version of this paper was delivered at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, December 1970, under the title ‘Up from the Genitals: Sexism in American Historical Writing.”[4]

“Up from the Genitals” – that title didn’t make the cut for the AHA program in 1970, though I’m guessing that it would today. Now, there are a few possible explanations for this discrepancy between the title as listed and the title as described in subsequent publications. Perhaps the AHA refused to print the full title of the paper, but gelded it for respectability’s sake. Perhaps the panelists decided not to include the full title of the paper in their panel submission, for fear that it would invite rejection. (Notice that the listed title of the first paper on the panel made no mention of the aforementioned Professor Palmer.)

“Up from the Genitals” – that title didn’t make the cut for the AHA program in 1970, though I’m guessing that it would today. Now, there are a few possible explanations for this discrepancy between the title as listed and the title as described in subsequent publications. Perhaps the AHA refused to print the full title of the paper, but gelded it for respectability’s sake. Perhaps the panelists decided not to include the full title of the paper in their panel submission, for fear that it would invite rejection. (Notice that the listed title of the first paper on the panel made no mention of the aforementioned Professor Palmer.)

It is also possible that the genitalia of the title were added after the fact. However, this seems unlikely. About a year after the 1970 AHA conference, the co-presenters wrote an account of their difficulties in finding a publisher for their paper; in this account, they referred to the paper by its full title. Further, they assumed that their readers – members of the Radical Historians Caucus and recipients of its newsletter – were already familiar with the paper as so titled.[5] And that was, it seems, the full title under which the paper was being submitted to journals – at least that’s what I gather from the Radical Historians Newsletter article. (I’ll have more to say about this fascinating account in a subsequent post.)

When the essay did at last find a home – in the first number of a new journal, Women’s Studies – its title was tame enough: “A Review of Sexism in American Historical Writing.” But in 1976, when the essay was revised for publication in Berenice A. Carroll’s edited collection, Liberating Women’s History: Theoretical and Critical Essays, it appeared in that work under a new title that recaptured some of the irreverence of the original iteration: “Historical Phallacies: Sexism in American Historical Writing.”[6]

That mid-1970s title – a return of the repressed? – reflects, I believe, the relative security or stability of women’s studies as a field compared to the situation just a few years earlier. Such a title couldn’t make the cut in the AHA program or in a scholarly journal in the early 1970s, either because it was too risqué for the publishers or too risky for that group of young historians in a young field seeking legitimacy. But by the mid-1970s, the co-authors of that paper, and their co-laborers from various disciplines working in the emerging field of “women’s studies,” had carved out and claimed some terrain in the academy from which they could safely lob not just serious scholarship but comedic irreverence aimed at challenging “the authoritarian grandeur and elitist majesty” of the field of history.

But they were able to do so not (or not only) because they scaled the ramparts of the establishment citadels of scholarship, but because feminist scholars had established their own parallel outlets for scholarship. The demurely titled “A Review of Sexism in American Historical Writing” found a place not in the AHR or the JAH or the Journal of Social History, or the American Quarterly – all places to which the paper had been submitted, per the 1972 account of the authors – but in a brand new journal devoted to women’s studies.

The emergence of such journals, and the growing demand for the kind of scholarship that they published, prodded the more mainstream journals to open their pages to feminist scholarship. “By building up audiences clamoring for more feminist scholarship,” writes Ellen Messer-Davidow, “they attracted mainstream presses and journals to the field. Once the growing market for feminist scholarship converged with profit-seeking publishers and the national reputations of feminist scholars converged with prestige-hungry departments, feminist studies was transformed from a backwater to a boom town.”[7]

But could there be a boom without a bust?

________________

[1] All information about the 1970 AHA meeting is taken from the Annual Meeting Program, available as a .pdf download from the website of the AHA. The AHA is working on scanning / making available more of these kinds of archival resources, and I am sure a donation in support of that project would be greatly appreciated and put to good use.

[2] John Layton Harvey, “Introduction: Robert Roswell Palmer: A Transatlantic Journey of American Liberalism,” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques 37, No. 3, Robert Roswell Palmer: A Transatlantic Journey of American Liberalism (Winter 2011), 8-9, 16n37. Harvey traces the history of this co-authored text to 1971, presumably the copyright date on the book-length manuscript distributed by the Radical Historians Caucus. But the 1970 conference presentation was, it seems, the public debut of this work or work-in-progress.

[3] Linda Gordon, Persis Hunt, Elizabeth Pleck, Marcia Scott and Rochelle Ziegler, “A Review of Sexism in American Historical Writing,” Women’s Studies 1, No. 1 (1972), 134.

[4] Gordon et al., 133.

[5] Gordon et al., “On Working Through Channels,” Newsletter of the Radical Historians Caucus 8 (Feb. 1972), 3-4.

[6] Linda Gordon, Persis Hunt, Elizabeth Pleck, Rochelle Goldberg Ruthchild, and Marcia Scott, “Historical Phallacies: Sexism in American Historical Writing,” Liberating Women’s History: Theoretical and Critical Essays, ed. by Berenice A. Carroll (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1976):56-74.

[7] Ellen Messer-Davidow, Disciplining Feminism: From Social Activism to Academic Discourse (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 151.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Good piece. Let me add a little more complexity to the picture of Robert R. Palmer possibly skulking around the Gordon et. al. session. Palmer was aware of the radical uprisings in the AHA in 1968-70 – the radical caucus ran Staughton Lynd against him for AHA president in 1969 — and he was not entirely unfriendly to the radicals and an emerging women’s caucus (led by Sandi Cooper, Berenice Carroll, Blanche Cook and others). After the turmoil at the 1969 meeting, Palmer as president commenced what I have always thought might be called a “pacification tour” of the provinces (perhaps, in today’s language, a “listening tour.”) I attended the Palmer meeting at the History Department at the University of Illinois at what was then called “Chicago Circle.” Others in the profession were driven by hysterical fantasies.(Richard Hofstadter – fresh from denouncing Columbia student radicals in 1968 — had called for a “counter-revolution” at the 1969 AHA; at the massively attended 1969 business meeting Genovese delivered a crazed attack on the Left, screaming, “We must put them down, we must put them down hard, once and for all!!” ) But Palmer was more open and oversaw the beginnings of what might be called a “Democratic Revolution” in the org. One of the fruits of this was the AHA committee on the rights of historians, overseen by Sheldon Hackney, with Al Young as the dynamic force. The committee began to face the realities of the wave of McCarthyism then sweeping through the profession: they investigated, put together an archive of testimony that deserves re-examination to day, and devised a new and stronger set of standards. Other fruits of Palmer’s Democratic Revolution included a broadening of membership in the AHA Council. In short, he was somewhat more open than other Establishment members. In the years that followed, the AHA never accomplished the fuller “greening” that changed the OAH, but Palmer and a few others saw the need for at least moderate change.

Jesse, thanks for sharing these details. I’m guessing the archive put together by Hackney, Young and their colleagues must be in the collections/publications of the AHA.