Edmund Wilson was incredulous about his friend John Dos Passos’s left-to-right political U-turn. He expressed this in verse:

On account of Soviet Knavery

He favors restoring slavery.

Like Wilson before me, I struggle to understand what compelled so many 1930s left-wing thinkers to become conservatives by the 1940s and 1950s. Below I grapple with an explanation for the left-to-right trajectory by way of a brief intellectual biography of James Burnham. Consider this a cautionary tale.

Burnham is a key thinker among the anti-Stalinist left that Alan Wald has written about in his 1987 book The New York Intellectuals: The Rise and Decline of the Anti-Stalinist Left from the 1930s to the 1980s. Burnham, along with Max Eastman, John Dos Passos, and Will Herberg, is also one of four people analyzed by John Patrick Diggins in his 1975 book, Up From Communism: Conservative Odysseys in American Intellectual History. (Note: these two books pair well together precisely because their ideological perspectives are vastly different. Diggins, who remained a Cold War liberal well past that ideology’s expiration date, wrote that his book “could be called a study of progress,” made apparent by the book’s title. The leftist Wald, on the other hand, calls the conservative turn taken by the left-wing intellectuals he studies “The Great Retreat”—he might have called it “Down from Communism”—and writes that Burnham had by the mid-1940s “settled upon a vulgar anticommunist ideology that would sustain his increasingly banal writings for the next forty years.”)

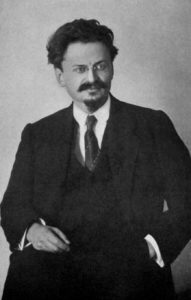

Unlike most New York intellectuals, Burnham was born into relative comfort, as his dad was a Burlington Railroad executive in Chicago. After an elite undergraduate and graduate education, Burnham took a position at New York University as a philosophy professor, where he hoped to explore his budding interest in Thomism. But like so many others, the Great Depression wreaked havoc on Burnham’s worldview and by 1930 he had begun reading Marx. Certain elements of Marx would remain with Burnham forever, well beyond his intellectual U-turn, particularly his hyper-skeptical view of liberal pieties. But it was Leon Trotsky who converted him to the cause of communism. Burnham was particularly transfixed by Max Eastman’s English translation of Trotsky’s The History of the Russian Revolution (1932).

Burnham’s friendship with fellow NYU philosopher Sidney Hook pushed him even further to the left. Hook’s 1933 book, Towards the Understanding of Karl Marx, which a reviewer called “the most significant contribution to Marxism which has as yet appeared in America,” melded pragmatism, the quintessentially American philosophy of his teacher John Dewey, to the radical internationalism of Karl Marx. Although Burnham loved Trotsky’s teleological and metaphorical approach to history, he recognized that such analysis would not translate well into an American context. Burnham was a sucker for the poetics of Hegelian dialectics, but was more convinced by Hook’s interpretation of Marx through Dewey’s pragmatic notion that all ideas must be verifiable in experience. “Any problem which cannot be solved by some actual or possible practice,” Hook wrote, “may be dismissed as no genuine problem at all.” The underlying premise was that if the Great Depression signaled the death knell of capitalism, Americans should turn to Marx, the greatest critic of capitalism, in their efforts to create a better tomorrow—but, only insofar as Marx’s ideas worked in the context of the American experiment.

Hook pushed Burnham to help organize the American Workers Party, a Trotskyist group. As Wald writes: “To the Trotskyist movement he brought some special qualities: a breadth of cultural knowledge, a writing style free of Marxist clichés, an aura of objectivity and impartiality, and a fresh perspective on indigenous political issues.” But by 1940 Burnham had left the Trotskyist movement and thereafter rapidly became one of its most scathing critics. By the early postwar years he was a full-blown anticommunist conservative, and would later become a regular contributor to Buckley’s National Review. How did this happen?

One of the most important debates among the sectarian left of the 1930s revolved around the following questions: Was Stalinism a bastardization of the Russian Revolution? Was it a betrayal of Marx? Or was Stalinism the logical conclusion of both Bolshevism and Marxism? Diggins wrote: “The ‘Russian Question’ forced veteran Marxists in Europe and America to discuss the problem of ends and means and the relationship between revolutionary violence and political conscience. Soon an intellectual search was under way to discover the fatal flaw in the history of communist theory and practice, the original sin, as it were, from which Stalinism took its malignant birth.”

Trotsky and most people in the various Trotskyist groups, including the Workers Party, declared that Stalinism was the result of conservative and bourgeois elements within the revolution that sought centralized authority over the proletariat. Burnham disagreed with Trotsky and quit the Workers Party, which led to desolation of the sort that often engenders a painful reexamination of one’s own ideas. Burnham had concluded that he had been seduced by a philosophy—the Marxist dialectic—which was entirely predicated on nothing more substantial than a series of metaphors. It was in the context of such self-reflection that he wrote his most famous book in 1941, The Managerial Revolution, which Diggins describes as “an answer to Trotskyism and a farewell to Marxism as a philosophy of history and as a program of hope—but not as a mode of analysis.”

More from Diggins’s astute analysis of The Managerial Revolution: “Marx was right about the past: the domination of the capitalist class, which ruled by virtue of its economic role in the course of development, made democracy historically impossible; he was wrong about the future: the domination of the new managerial class, which rules by virtue of its technological and organizational necessity, makes democracy eternally impossible.” This is why C. Wright Mills later gave Burnham the unflattering title, “The Marx of the Managers.”

Diggins continued: “Managerialism, of which Stalinism was an expression, evolved logically from Marx’s assumption that all power and authority derived from possession of the means of production. As sociological phenomena, managerial rule, technological authority, and bureaucratic domination could be traced back to the means of production, the ownership of which Marx had regarded as the sole source of power and freedom.” In short, Marx’s notion of historical development, which was grounded in the Hegelian dialectic, was dead wrong. But Marx’s notion of power, which unlike liberalism saw through the sham of sentimental higher principles like justice, was right in that who controlled production controlled society.

Burnham had given up on Marx’s socialist revolution but had retained Marx’s clear-eyed skepticism of liberal shibboleths. From there the trek to conservatism was short, since Burnham could no longer cling to socialism and he had never clung to liberalism. Burnham’s next book, The Machiavellians (1943) illustrated his deep disdain for democracy and his growing uncritical fascination with elite rule.

At an abstract philosophical level, Burnham’s journey from far left to far right makes some sense, and in this it might support the “horseshoe theory” which posits that the far left and far right are closer to each other than either is to the political center. It also might support James Livingston’s longstanding argument that socialism and Marxism and other isms don’t have particular or predictable left or right political valences. But I am highly skeptical that these are the correct conclusions to draw from the cautionary tale of Burnham, and not only because his Marxism was, like Hook’s, always a peculiar sort. More to the point: How does someone go from supporting ideas that amount to a rationale for universal equality in one second, to supporting ideas that amount to a defense of rigid hierarchy in the next?

I have not yet solved the riddle of left-to-right turncoats. Perhaps this riddle is unsolvable. But I’d love to hear your ideas!

20 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

hannah arendt has a thing on former vs. ex communists. adorno’s thing on “hating tradition properly” in minima moralia is related. see also norman finkelstein on christopher hitchens “model apostate”

Thanks for the suggestions.

Andrew,

In Daniel Bell’s 1979 essay “The New Class: A Muddled Concept,” reprinted in his collection The Winding Passage, Bell quotes Burnham as writing that managers “will exercise their control over the instruments of production…through their control of the state which in turn will own and control the instruments of production.”

There are dangers in taking a quote out of its full context, but if Burnham did indeed mean this — i.e., the state will own the means (or “instruments”) of production and “managers” will in turn “control” the state — then his vision represents a complete failure of prognostication at least w/r/t the U.S., where the state never came close to owning most of the means of production.

Bell says the term “managers” turned out to be elusive, and for that matter the term “control” is not that clear either. But one thing that I think is quite clear, and one doesn’t have to be a Marx expert to arrive at this conclusion, is that Marx would not have seen “managers,” really however defined, as owners of the means of production.

On the much-discussed (at one time, at any rate) question of the relation between Stalinism and Marxism: you don’t have to be a Trotskyist to think Trotsky was rather considerably closer to the truth here than Burnham.

It’s one thing to argue Bolshevism “had” to lead to an authoritarian regime and that there was little prospect, esp. given the historical circumstances, that it would lead to anything approaching a workers’ paradise. It’s quite another thing to argue that Stalin’s murder of (tens of) millions of people was a “logical” outgrowth of anything Marx (or even probably Lenin, for that matter) wrote. It’s hard to take the latter argument, esp. w/r/t Marx, seriously, imho.

p.s. I realize I haven’t addressed your question of how/why people go from the far left to the far right. I’ll leave that to others.

Thanks for these comments Louis–I think I agree with everything you write here!

Do you know how Burnham dealt with the reaction from colleagues and friends to his early departures from Trotskyism? I feel like the dynamics of reaction on the personal level have such an effect on the political one that they’re often essential to storylines like these.

Good question. I don’t know, yet. Going to do more digging on Burnham today. But I agree with you that the personal really matters. Norman Podhoretz seems to have become a neocon because his friends hated his book Making It. The hyper-sectarian politics of Trotskyism led to a lot of personal schisms that perhaps is somewhat responsible for so many Trots becoming right-wingers.

Perhaps looking at it through a lens of secularization is appropriate, too.

It might be that Burnham was rejecting a certain sense of secular modern humanism for an out-of-time hierarchal ancien regime…

Clearly, I’ve been reading too much Charles Taylor. But it might be useful!

I don’t think this was Burnham’s thing, but was certainly true for some. Thanks.

A timeline of Burnham’s 1930s political activism gives some sense of the intense, dare I say insane left-wing sectarianism of that era that breeds the opposite of solidarity and perhaps lends itself more easily to the reactionary turn: in 1933, with Sidney Hook, Burnham helped organize the American Workers Party led by AJ Muste. In 1934 that party merged with the Communist League of America to form the U.S. Workers Party. In 1935, Burnham and the other Trotskyists in that party supported a merger with the Socialist Party. It was in this period—1935-1937—when Burnham became friends with Trotsky. In 1937 things began to go south for Burnham and the Trotskyist movement. That year the Trotskyists were expelled from the Socialist Party and formed the Socialist Workers Party. Within the SWP, factions formed around how to think about Stalinism. The majority faction, led by James Cannon and supported by Trotsky, argued that the Soviet Union was degenerative but that it remained a workers state and must be defended against imperialism. Burnham, allied with Max Shachtman, argued that the USSR had become yet another if different imperialist power that did not merit their critical support. This position hardened after the Nazi-Soviet Pact and even more after Stalin’s regime invaded swaths of eastern Europe and Finland. In 1940 Burnham wrote a text breaking with dialectical materialism, and he and Shachtman broke with the SWP and formed a separate Workers Party (named yet again). But then that same year he quit the Workers Party, further distanced himself from Marxism, and essentially withdrew from left-wing political activism forever.

As this narrative highlights, the period of the Nazi-Soviet Pact followed by US-Soviet alliance during World War II was a kind of one-two punch to contemporary Trotskyist analyses of the Soviet Union.

The CPUSA, of course, went through a similar series of switchbacks, if its positions were less up for grabs. Having pushed for antifascist interventionism before the summer of 1939, the Party urged neutrality when war actually broke out and then went back to an interventionist position in June 1941, when the German invasion of the Soviet Union began. The Party bled American membership during the N-S Pact period.

There were fewer Trotskyists…and they, on the whole, more willing to take their toys and go home. As you note, Trotsky urged neutrality in 1939. A year later he was dead, a victim of the regime whose defense he had just called for. With the Old Man gone, the Troskyist (and recent ex-Trotskyist) response to events in the summer of 1941 was even more fragmented.

Have you picked up Daniel Oppenheimer’s book on this? I haven’t gone through it yet, but it could be useful. I know he writes about Burnham in it. He might offer another perspective, being a self-labeled ‘conservative Leftist’ and whatnot (http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/why-i-am-a-conservative-leftist/).

I have Oppenheimer’s book sitting on my desk right now and am about to read his Turnham chapter. I had read other chapters in the book–it’s quite good–but had forgotten there was one on Turnham. Duh!

As there was no “conservative movement” in the immediate postwar period all these people had in common was their disillusion with the Marxist dialectic and its political manifestations. The Right was Sen. Taft, Cardinal Spellman, HL Mencken and, if the current Pearlstein is to be believed, the Grand Dragon of the KKK. Cue George Nash on Wm. F. Buckley. But even when Buckley offered them refuge in National Review they weren’t happy. Max Eastman, who had discovered the free market, quit because he thought NR was too religious. Whittaker Chambers bowed out because NR wasn’t religious enough. I can’t imagine that Burnham and Russell Kirk would have anything to say to each other around the water cooler. Conservative “fusionism” (Frank Meyer’s term) was NR’s way of papering over their differences for public consumption. So why did they decide to make common cause with each other (and with the Republicans and Cardinal Spellman and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce) instead of retaining a “politics of hope” and becoming liberal anti-Communists like Reinhold Niebuhr and Arthur Schlesinger: Is that the question?

B. Huberty:

So why did they decide to make common cause with each other (and with the Republicans and Cardinal Spellman and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce) instead of retaining a “politics of hope” and becoming liberal anti-Communists like Reinhold Niebuhr and Arthur Schlesinger: Is that the question?

Or even more to the point in Burnham’s case, why didn’t he follow Max Shachtman’s protég&ecaute;[*] Irving Howe into the Howe/Harrington version of democratic socialism?

[*] maybe not quite the right word, but close enough

p.s. never try html after 9:30 p.m.

I meant protégé, obviously.

I’m thinking maybe disgust has something to do with it. Lately I’ve seen some articles on the greater role disgust plays in conservative over liberal politics. They just couldn’t bring themselves to sing ‘happy days are here again.’

Taken literally, this is dubious (they wouldn’t have to have actually sung it) and taken metaphorically I’m not sure I get what you’re suggesting. (What was the object or target of this supposed disgust? )

Anyway, it doesn’t really address my variation on your question (see above). The answers here presumably lie mainly in each person’s circumstances, background, psychology, and peculiarities (meant in a neutral, not a negative, sense).

Gary Dorrien in The Neoconservative Mind (still one of the better books on early neoconservatism, in my opinion) sees Burnham as a key figure in the prehistory of neoconservatism and has some interesting things to say about him (I know you you probably know this, but I figured I’d toss this into the comment thread for others who are interested).

I took a grad seminar on the History Communism/Anti-Communism a few years ago at UW-Madison (with Prof. Tony Michels) in which we read Wald, Diggins, and a host of other scholars who wrestled with this question of why the New York Intellectuals turned away from the left. As a young, impressionalbe scholar (some might even call me a “millennial,” which I’ll neither confirm nor deny) I had two consistent reactions to this historiography:

1. Do we really need to spill this much ink to figure out why a handful of Trotskyists changed their minds once upon a time? In other words, I was much more interested in why Wald, Diggins, et.al. got so obsessed (and were so incredulous) about “the turning” than I was in why Burnham, Eastman, et.al. made the turn. In this sense, I’m sympathetic with Livingston. Moreover, I’m inclined to see the persistent left/right framing of ideas, of “-isms,” as a curiosity worthy of study in its own right.

2. Why didn’t this historiography talk more about the effect of World War II? Not about the Nazi-Soviet Pact or about Stalin, but about the war itself. As late as 1940, when Burnham started his conversion, it might have been reasonable to assume that the future would either by fascist, communist, or some unholy alliance of the two. Then the Germans and Russians slaughtered millions of people across the half of Europe that lay between them and in the process reduced each others’ industrial capacity to rubble. That unparalleled cataclysm did nothing less than move the “pivot of history” (pace Mackinder) from Eastern Europe to the North Atlantic (and, after colonial empires collapsed after the war, maybe now its somewhere in the Pacific). The war – by which I mean the violence and the destruction of entire population centers, not debates over political systems – was the single most important historical development of that generation – and, quite possibly, of any generation in at least the past two centuries.

From that point of view, Burnham’s intellectual contribution was not in his turning to the right, it was in his anticipation in 1940-41 that something seismic was happening and that a new philosophical language would be needed to conceptualize what was to come. That attempt to innovate is what makes “The Managerial Revolution,” whatever its limitations, compelling reading even today. It’s also what made Burnham’s later conventional conservatism “increasingly banal,” as Wald put it (as, in my view, was his early conventional leftism – although perhaps arcane is a better word than banal). I would say something similar about writers like Orwell and Arendt – the times of which they wrote were as important in shaping their thought as were the theories that informed their work. Before the war, leftists of various sects debated how the world ought to change. During the war, the world actually changed. It’s not surprising that some political opinions changed along with it.