Every two years, the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture holds a remarkable conference. If there was an equivalent of “must-see tv” in the world of religious studies, this is it. The conference does well because it consistently hits the trifecta for these kinds of events: it invites dynamite speakers, it organizes discussions around fascinating topics, and it uses a format that encourages intelligent, sustained exchanges. Of particular note to the S-UISH gang, this year’s speakers include Matt Hedstrom, Melani McAlister, Paul Harvey, Tisa Wenger, Marie Griffith, and Katie Lofton (the 2014 S-USIH conference keynote). If you are in striking distance of Indianapolis, get thee to the Biennial!

Every two years, the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture holds a remarkable conference. If there was an equivalent of “must-see tv” in the world of religious studies, this is it. The conference does well because it consistently hits the trifecta for these kinds of events: it invites dynamite speakers, it organizes discussions around fascinating topics, and it uses a format that encourages intelligent, sustained exchanges. Of particular note to the S-UISH gang, this year’s speakers include Matt Hedstrom, Melani McAlister, Paul Harvey, Tisa Wenger, Marie Griffith, and Katie Lofton (the 2014 S-USIH conference keynote). If you are in striking distance of Indianapolis, get thee to the Biennial!

Headlining a discussion at this event on religion and the American state is one of S-USIH’s founding members, David Sehat. If you have not had the pleasure of hearing David speak, here is your opportunity to watch him engage a subject that, frankly, he speaks on with commanding authority. This specific event also plays incredibly well to David’s strength as a debater. He will join Lerone Martin of Washington University-St. Louis and Melissa Wilcox of UC-Riverside at a small table in a room that resembles a medical examination lab—the participants in the conference sit in seats slightly elevated and surrounding those featured in the discussion. The three discussants engage each other for a period of intellectual sparing before opening the conversation to the audience. When a scholar makes it to the table at one of these events, the experience confers a degree of influence over the field. What gets said in the “round” often shapes what gets written about later.

Headlining a discussion at this event on religion and the American state is one of S-USIH’s founding members, David Sehat. If you have not had the pleasure of hearing David speak, here is your opportunity to watch him engage a subject that, frankly, he speaks on with commanding authority. This specific event also plays incredibly well to David’s strength as a debater. He will join Lerone Martin of Washington University-St. Louis and Melissa Wilcox of UC-Riverside at a small table in a room that resembles a medical examination lab—the participants in the conference sit in seats slightly elevated and surrounding those featured in the discussion. The three discussants engage each other for a period of intellectual sparing before opening the conversation to the audience. When a scholar makes it to the table at one of these events, the experience confers a degree of influence over the field. What gets said in the “round” often shapes what gets written about later.

ROCK, RACE, AND RANDALL STEPHENS

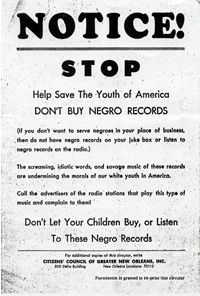

Last week, the RAAC hosted religious studies scholar and friend of S-USIH Randall Stephens. Randall has a new book coming out from Harvard University Press entitled, The Devil’s Music: Christianity and Rock since the 1950s and he might be familiar to folks for his ability to write across platforms—he is as likely to appear in the New York Times and the Chronicle as in an university press. The presentation he gave on his latest book project took up the intersection of Evangelical social criticism, the emergence of Rock ‘n Roll, and the racial politics of mid-century America. Those familiar with Christians freaking out in earlier periods over jazz and blues and in a 1980s and 1990s over heavy metal and rap, will not be surprised that some Evangelicals also lumped rock music in with communism and integration as evils that beset American society.

Last week, the RAAC hosted religious studies scholar and friend of S-USIH Randall Stephens. Randall has a new book coming out from Harvard University Press entitled, The Devil’s Music: Christianity and Rock since the 1950s and he might be familiar to folks for his ability to write across platforms—he is as likely to appear in the New York Times and the Chronicle as in an university press. The presentation he gave on his latest book project took up the intersection of Evangelical social criticism, the emergence of Rock ‘n Roll, and the racial politics of mid-century America. Those familiar with Christians freaking out in earlier periods over jazz and blues and in a 1980s and 1990s over heavy metal and rap, will not be surprised that some Evangelicals also lumped rock music in with communism and integration as evils that beset American society.

While Randall’s argument is broad and extremely well-documented, I want to highlight just a couple of points he presented. The first was the persistence of linking rock to the “beat of the jungle” in Evangelical publications. The overt racialization of music of all things African-Americans is nothing new, but the racialized criticism of rock took a different line because so many of the popular performers (and thereby promoters) of it were white. In order to “color” white performers (from Elvis on down), Evangelical critics tried to convince their audiences that the influence of “Africa” would make one “black.” It was an insidious argument that found expression in the second item that I found fascinating.

While Randall’s argument is broad and extremely well-documented, I want to highlight just a couple of points he presented. The first was the persistence of linking rock to the “beat of the jungle” in Evangelical publications. The overt racialization of music of all things African-Americans is nothing new, but the racialized criticism of rock took a different line because so many of the popular performers (and thereby promoters) of it were white. In order to “color” white performers (from Elvis on down), Evangelical critics tried to convince their audiences that the influence of “Africa” would make one “black.” It was an insidious argument that found expression in the second item that I found fascinating.

White rock musicians would testify in front of fellow evangelicals that they understood intimately how “the beat” led them toward sin. I hope Randall will provides amble and detailed examples of such testimonies from his book on a website. Further, Randall extends such clear moments of racially inflected warnings about rock to the eventual (perhaps even inevitable) incorporation of rock into church services. In other words, if one couldn’t deny the power and attraction of “the beat” then why not harness that beat for God’s work?

Michael Kramer also takes up the history of race and rock in a typically well-written, expertly argued review of Jack Hamilton’s book, Just Around Midnight. Michael writes that Hamilton “develops a ‘counterhistory’ in which musicians continually trouble the position of rock as white during the 1960s. In ways often forgotten or overlooked, the musicians and their sounds cut across racial boundaries. Recovering their efforts, Hamilton emphasizes how they critiqued or rebelled against racial categorizations and hierarchies even though they never quite transcended or overturned the existing racial order.”

I am especially interested in thinking through the connection, if any, of the rebellious rock of bands such as the Replacements to the politics of their era. While I love the music, I found myself deeply conflicted or ambivalent about the band after reading their biography in Trouble Boys: The True Story of the Replacements by music critic Bob Mehr. It seemed to me that Paul Westerburg, the lead singer, guitarist and all-around instigator of the band, avoided any contact with African-American musicians even though he was heavily influenced by sounds from the middle south—Nashville in particular. I also found myself wondering what kind politics this punk band encouraged. Their legendary drunkeness and self-destructiveness struck me as coterminous with the people in Jefferson Cowie’s Stayin’ Alive. In that sense, were the Replacements, who hail from Minnesota, a bellwether of the upper Midwest’s drift toward Trumpism? Maybe we’re all Bastards of Young.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Cross posted from Facebook page: I’ll be interested what Kevin Mattson has to say about punk politics. I think of journalist Michael Azerrad’s book Our Band Could Be Your Life and the chapter on The Replacements. The politics are there, just not in the way that we’d like them to be, exactly. Intersections or race, class, gender, and region at play. Beyond the Replacements, there’s a few issues here to consider, I think: music and the people making the music shouldn’t be collapsed into one and the same. They are linked, to be sure, but not in any simplistic way. After all, James Brown supported Richard Nixon. Does that mean the music he made didn’t have a kind of radical politics too (and not the radicalism of Richard Nixon, mind you!)? Even more importantly, not even the making of a musical track necessarily relates to its political dimensions. After all the studio recording of “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)” actually has white and Asian children singing with Brown, not African-American children. Does that mean the track doesn’t speak on many frequencies (the lower as well as others?) in powerfully political ways? Not to my ears. Especially if you listen to a live version from 1968 such as https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DuP4MafTDb0 followed by https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oJ2TLOKy_kk. Anyways, this an area in which historians need to engage more with popular music studies and the deep lit there on how to consider the politics of pop music—no simplistic topic, that, and one in which ambiguities and multiple registers tend to manifest themselves in place of party lines and straightforward ideological positions (wouldn’t those be boring as pop songs anyway–wrong form). Recent EMP Pop Music Conference focused on this topic with many rich, provocative, and powerful presentations, http://www.mopop.org/programs/programs/pop-conference/.