“It is a furious book. At times vitriolic, and often captious, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual is nihilistic at its worst and a source of terse, seminal insight at its best. Cruse may not be the gadfly of Athens, but he is certainly the horsefly of Harlem.” –Robert Chrisman, “The Crisis of Harold Cruse,” Black Scholar, Volume 1, No. 1

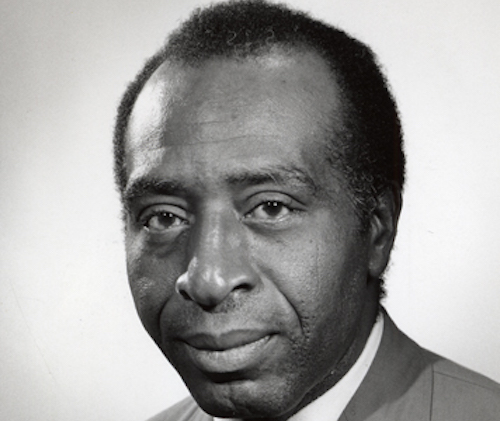

When any curious reader picked up a magazine of African American culture and arts, such as Negro Digest, Freedomways, or Black Scholar in the late 1960s, they no doubt encountered some sort of opinion about Harold Cruse. The irascible, multilayered intellectual who had made Harlem his home base for years, Cruse would shake up the world of black letters and arts in 1967. In an age when writers such as Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin continued to set the standard; where writers like Eldridge Cleaver and Albert Murray, for vastly different reasons, fought against the grain; and artists such as Margaret Walker and Gwendolyn Brooks worked harder than ever to push the envelope; Harold Cruse wrote a work of big ideas and even bigger verbal fireworks to catch the attention of every important American intellectual in the late 1960s.

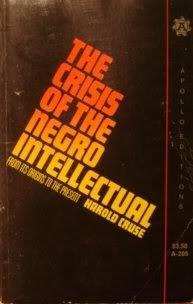

Harold Cruse’s impact on African American—not to mention American—intellectual history is difficult to measure. Talking about African American intellectual history since 1967 means, ultimately, confronting the ideas, legacy, and perception of Harold Cruse. His magnum opus, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, was written and released just as the Civil Rights Movement undertook, at least in the eyes of many  Americans, a transition into an angrier Black Power Movement. Yet Cruse’s work only tangentially touched on this change in black American society. He was more concerned with the long history of African Americans and the American Left—a history that would shape the direction and purpose of both the Civil Rights Movement and black artists who were all politically active in the sixties.

Americans, a transition into an angrier Black Power Movement. Yet Cruse’s work only tangentially touched on this change in black American society. He was more concerned with the long history of African Americans and the American Left—a history that would shape the direction and purpose of both the Civil Rights Movement and black artists who were all politically active in the sixties.

At the Society of U.S. Intellectual History, 2017 has become the year of the roundtable. Our most recent roundtable covered modern responses to David M. Potter’s The Impending Crisis. Coming in October is a roundtable commemorating the centennial of the Russian Revolution. Discussing The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual between spirited debates about the American Civil War and the rise of Communism, on reflection, makes perfect sense. Cruse wrote at the intersection of race, class, art, and ideology, grappling with a black intellectual tradition that he saw as too weak to provide proper leadership to black Americans.

Frankly, it would be impossible for me to cover every single response to The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual after it was released in 1967. In the past, I have written for S-USIH about the various responses to Crisis from a variety of sources. White leftists—most notably Christopher Lasch—found the book fascinating and an essential read. African American radicals, on the other hand, were divided over the book. The historian Vincent Harding, for example, believed the book to be important, but was also dismayed by Cruse’s lack of coverage of intellectuals beyond Harlem.

Cruse himself would be defined by The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. Sometimes, intellectuals write books at a perfect moment in history. That was the case for Cruse. Already somewhat established in leftist circles for various essays about Cuba, civil rights, and race in America, Cruse’s tome made him a sudden intellectual star among black intellectuals. In that tumultuous year of 1967, when so many Americans struggled to figure out why, exactly, African Americans did not seem satisfied after the passage of the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act, Crisis of the Negro Intellectual seemed to provide some new food for thought.

Every black intellectual in America has had to respond to the book’s many arguments in some fashion. Cruse’s arguments about the relationship between African Americans and Jewish leftists lingers on through the works of intellectuals such as Cornel West. His view of the centrality of black art to black  liberation is part of a long tradition of concern about the relationship between culture and politics—written about by people such as W.E.B. Du Bois. His critiques of the Communist Party’s views on race presage a wide range of intellectual works—from Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism to the monographs of Michael C. Dawson—all complicating how the left has failed time and again on the question of race in American society.

liberation is part of a long tradition of concern about the relationship between culture and politics—written about by people such as W.E.B. Du Bois. His critiques of the Communist Party’s views on race presage a wide range of intellectual works—from Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism to the monographs of Michael C. Dawson—all complicating how the left has failed time and again on the question of race in American society.

The various roundtable entries all cover different aspects of Cruse’s book. Monday, we begin with an entry from Daniel Geary, author of Beyond Civil Rights and an expert on the intellectual history of the civil rights and Black Power eras. His piece forces us to consider why, exactly, Cruse is so important to African American intellectual history. Then, Andrew Hartman will highlight the deep and complicated relationship between Cruse and the American left, bringing in some much-needed commentary on modern debates too. Third, Holly Genovese will highlight the tumultuous intellectual relationship between Cruse and James Baldwin, a man who is bitterly denounced (like so many others) in Cruse’s book. Finally, Josh Myers, of Howard University’s Africana Studies department will close out the roundtable, putting Cruse’s book in the context of the Black intellectual tradition.

This weekend I shall offer up a brief historiographical essay on the response to Cruse over the decades. But until then, I hope you enjoy this week’s roundtable—and consider what a man like Cruse, who never completed a college degree and yet read and wrote his way to being a giant in the field of intellectual history and African American Studies, could teach us even today.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Sounds good, Robert. Looking forward to this, and to joining S-USIH “Back in the USSR” next month!

Thanks for putting together this round table. I’m looking forward to an education about Harold Cruse! – TL

This is the second time in my career that I ever encountered anyone who thought The Crisis was an intellectual history rather than a polemic by scholarly essayist trying to have an impact on his time. The other time it was by a historian who used it as a foil to launch his career. Yet here we are fifty years later and the crisis is still a must read by any black intellectual.

Harold Cruse’s work The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual is one of the most useful and comprehensive works ever written on where the Black intellect has been and where it needs to go. However, the critiques of this work have been written by those people who have certain interests to support and really haven’t read the work but rather have read their biases into the work and have thus criticized Cruse as a person rather than analyzed his work.